The Myth of Natural Talent. and Why Do We Still Believe in It by Jarek Orzel Medium (1)

The myth of natural talent. And why do we still believe in it | by Jarek Orzel | Medium #

Excerpt #

These sentences emphasize the idea that talent is an inherent quality, suggesting that the person possesses a natural inclination or aptitude in a specific domain. The belief that talent is an…

[

]( https://medium.com/@orzel.jarek?source=post_page-----ac74787f5826--------------------------------)

Photo by Etienne Girardet on Unsplash

You have probably encountered some of the following sentences in your life:

- “Amy has a gift for languages. She is speaking without any effort.”

- “Tom is incredibly talented at painting. His brushstrokes are truly mesmerizing.”

- “He’s a natural-born leader. His ability to inspire people and motivate others is exceptional.”

- “Jane has a natural talent for singing. Her voice is captivating and effortless.”

These sentences emphasize the idea that talent is an inherent quality, suggesting that the person possesses a natural inclination or aptitude in a specific domain.

The belief that talent is an innate, fixed trait is relatively widespread among people. This understanding suggests that individuals are born with specific abilities and talent is a natural predisposition that cannot be significantly changed or improved upon.

I have a problem with that talent perception. It harms how people perceive their learning opportunities.

Artificial definition #

The root of the problem is that a talent word is not clear. Its meaning is vague and can be interpreted very differently by people. The concept of talent can be a source of controversy, precisely because it is an artificial or socially constructed category, rather than a natural or objective one. The notion of talent is based on subjective judgments about what constitutes exceptional ability or potential, and these judgments may vary across cultures, societies, and historical periods. I can find at least five different interpretations for a talent word:

- Innate Ability: in that interpretation, talent is viewed as an innate, inherent ability that certain people are born with. They believe that talent is a natural predisposition (for some people even predestination) or aptitude in a specific area, such as music, sports, or art. This perspective often implies that talent is fixed and unchangeable.

- Unique Combination of Abilities: some argue that talent is a combination of various abilities, such as intelligence, creativity, perseverance, and emotional intelligence. They believe that it is the unique blend of these attributes that leads to exceptional opportunities in a particular field.

- Passion and Motivation: Another perspective is that talent is closely tied to passion and motivation. People who are deeply interested and motivated in a specific area are often seen as having a natural talent for it. This perspective suggests that talent is nurtured through genuine enthusiasm and dedication.

- Cultural and Social Factors: Talent can also be viewed as a product of cultural and social factors. Some argue that talent is heavily influenced by opportunities, access to resources, quality education, and cultural support systems. They emphasize the role of the environment in nurturing talent.

- Skills and Expertise: talent is perceived as a result of developing exceptional skills and expertise through dedicated practice and effort. They believe that while individuals may have different starting points, talent emerges as a product of deliberate practice, experience, and learning.

Unfortunately, the idea of innate talent (#1) is quite common, including media portrayals of prodigies, societal narratives around exceptional talent, and the notion of “natural-born” geniuses in certain fields. This understanding can be deeply ingrained and influence how people perceive their abilities and the abilities of others.

The purpose of any concept or category is to serve a practical function, whether it’s to explain phenomena, guide decision-making, or promote understanding. If a concept like talent is found to have negative implications, such as limiting individuals’ beliefs in their own potential or perpetuating inequalities, it may be necessary to reframe or replace it with alternative approaches that are more empowering and inclusive.

I think that talent is a combination of all the above interpretations except the first one (people have different starting points, but I would not call it a talent). So talented people should have:

- abilities (intelligence, personality, temperament) that would predispose them to develop skills in a given domain (#2 and #3). However, some of these abilities can be acquired with practice.

- social environment that allows learning and improvement (#4)

These factors usually can direct a person to achieve expertise (#5) by working hard for a long time. However, the question is whether people without some of the above factors can still be successful in a given field. Probably yes, but they need much more effort and time in comparison to people who already have some personality traits and good circumstances in place. They need deliberate practice.

Deliberate practice #

Deliberate practice is a method of focused, purposeful, and systematic training that can help individuals develop their skills and expertise in a particular area. Anders Ericsson is the person who introduced that concept and carried out a lot of research in that field.

His research has shown that deliberate practice is a key factor in achieving high levels of skill and expertise in various domains, including music, sports, chess, and other areas. Deliberate practice is a more important predictor of success than natural abilities alone.

Therefore, while some predisposition aspects can provide a helpful starting point, deliberate practice is essential for developing mastery in any skill or field. Through deliberate practice, individuals can identify their weaknesses, receive feedback, and work systematically to improve their performance and reach their full potential.

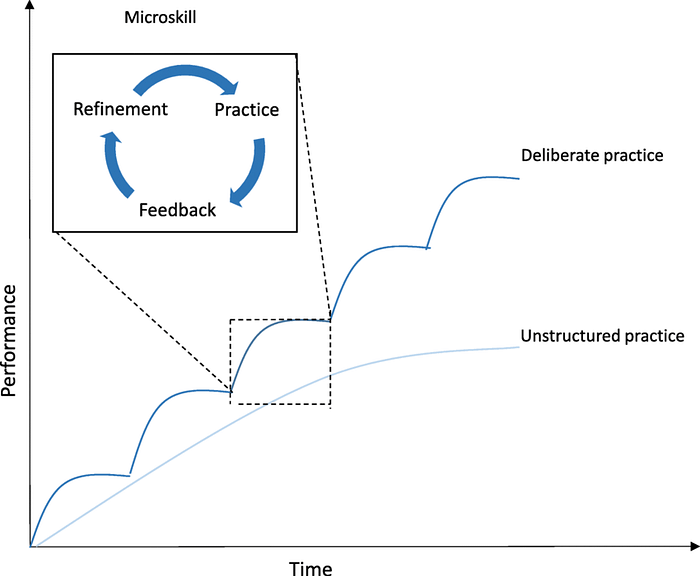

Deliberate practice vs unstructured practice ( source)

Deliberate practice is not only hard working. It is characterized by the following traits (that are not necessarily present in unstructured practice):

- Clear Goals: Deliberate practice requires setting clear, specific, and challenging goals that define the desired outcome or skill to be developed. Having a clear direction helps focus efforts and provides a sense of progress.

- Feedback: Deliberate practice involves receiving regular and specific feedback on performance. Feedback helps identify areas for improvement, highlights strengths and weaknesses, and guides adjustments to the practice approach.

- Repetition and Intensity: Deliberate practice involves repeated and focused engagement with the specific skill or task. It requires sustained effort and intensity, pushing beyond one’s comfort zone to continuously challenge and stretch abilities.

- Purposeful Design: Deliberate practice is purposefully designed to target specific aspects or components of the skill being practiced. It involves breaking down complex tasks into manageable parts and systematically working on each component to improve overall performance.

- Effortful Engagement: Deliberate practice requires full and concentrated mental and physical engagement. It involves pushing oneself to the limits of current ability, maintaining concentration, and exerting effort to refine and improve performance.

- Adaptation and Iteration: Deliberate practice involves continuously adapting and adjusting the practice approach based on feedback and progress. It requires a willingness to reflect on weaknesses, experiment with different strategies, and make iterative improvements.

- Expert Guidance: Deliberate practice often benefits from expert guidance or coaching. Expert instructors can provide guidance, structure practice sessions effectively, and offer insights and strategies to help individuals improve more efficiently.

The following statements from Ericsson’s writings demonstrate the power of deliberate practice while downplaying the value of innate ability:

- “We now understand that there is no such thing as a predetermined ability or talent. With the exception of a few basic physical limitations, most people can learn almost anything with the right kind of training and motivation.” ( source)

- “The most important point is that natural talent is not required for expert performance. Innate ability might determine how quickly a skill is learned initially, but deliberate practice is necessary for continued improvement.” ( source)

- “The idea that some people are born with a natural talent for a particular skill is a myth. What sets experts apart is not some mystical innate ability, but rather the amount and quality of their deliberate practice.” ( source)

- “Our research shows that deliberate practice is necessary for the development of expert performance, regardless of initial ability level. What sets experts apart is not their natural talent, but rather the quality and quantity of their deliberate practice.” ( source)

Matt Syed in his inspirational book Bounce: The myth of talent and the power of practice highlights the importance of a growth mindset and purposeful practice but also emphasizes the role of environmental factors, such as access to quality coaching, resources, and opportunities, in nurturing talent and facilitating high achievement.

Why do we still struggle to succeed? #

If there is nothing like innate talent, why success or expertise is rather something rare? If you can achieve almost any skill by deliberate practice, why hardly any get there? I have four reasons.

1. Deliberate practice is hard #

Deliberate practice is a demanding and challenging life path. It requires significant effort, discipline, and lifestyle adjustments, including prioritizing rest and finding peak productivity times.

Deliberate practice is not for everyone ( source)

An example of someone who set up their whole life towards gaining a skill is Mozart, the renowned composer and musician. From a young age, Mozart demonstrated an exceptional inclination for music, but his mastery was not solely attributed to innate ability. He also dedicated himself to deliberate practice and structured his life around developing his skills. Mozart began learning music from a very young age, receiving formal training from his father, who was a renowned musician and composer. Mozart’s father structured his education around music. He provided Mozart with rigorous training and opportunities to perform and compose music from a young age, encouraging him to continually challenge himself and strive for excellence. Mozart devoted countless hours to practice and composition throughout his life. He maintained a disciplined practice schedule, often spending hours each day honing his craft and refining his skills. Mozart’s pursuit of musical mastery required sacrifices in other areas of his life. He dedicated himself wholeheartedly to his art, prioritizing music above all else and forgoing other pursuits and distractions.

Continuous skill improvement is constant balancing on the comfort zone’s verge. It demands being comfortable in uncomfortable situations (outside your comfort zone). Not everyone is ready for it.

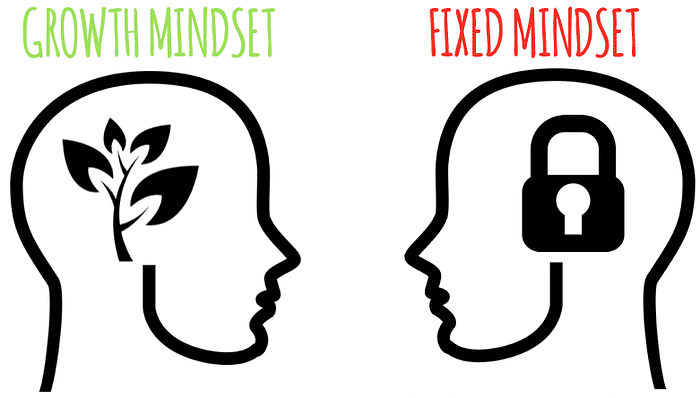

2. Fixed mindset #

Fixed mindset individuals may believe that if they have to put in effort to succeed, it means they lack natural talent. As a result, they may avoid trying new challenges that require effort, preferring activities where they can easily demonstrate their existing skills.

A fixed mindset locks our development opportunities ( source)

In Carol Dweck’s book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, she provides numerous examples to illustrate how a fixed mindset can limit skill acquisition. One such example involves students who believe that their intelligence is fixed and cannot be changed. Dweck describes a scenario where students with a fixed mindset encounter challenges in their academic pursuits. These students may believe that intelligence is an innate trait, and they either have it or they don’t. As a result, when faced with difficult tasks or academic setbacks, they may interpret these experiences as evidence of their lack of intelligence.

For instance, imagine a student named Jack who believes he is either naturally good or bad at math. Whenever Jack encounters a challenging math problem that he struggles to solve, he becomes frustrated and demotivated. He may believe that his difficulty with math is a sign that he lacks the inherent ability to succeed in the subject. Consequently, Jack may avoid seeking help or putting in extra effort to improve his math skills because he doubts his capacity to do so.

3. The multiplier effect #

Geoff Covin in his great book Talent is overrated, claims that one of the reasons we perceive talent as something inborn is the multiplier effect. It refers to how small advantages or gains can lead to disproportionately large outcomes over time.

The relative age effect is a prime example of the multiplier effect. In contexts like sports or education, being slightly older within an age group can lead to early success, which then provides more opportunities for practice, coaching, and recognition.

In Malcolm Gladwell’s book O_utliers: The Story of Success_, he discusses the relative age effect in the context of hockey, particularly in Canadian youth hockey leagues. In many youth hockey leagues, eligibility is determined by birthdate, with a specific cut-off date for each age group. For example, if the cut-off date is January 1st, children born in the same calendar year are grouped, regardless of whether they were born in January or December. Children born earlier in the year tend to be physically larger and more mature compared to those born later in the year, especially at younger ages. As a result, they may have a developmental advantage in terms of size, strength, and coordination. Coaches and scouts often select players for competitive teams based on performance, which can be influenced by physical attributes such as size and maturity. Consequently, children born earlier in the year are more likely to be identified as talented and receive opportunities for advanced training and development. Once identified as talented, players born earlier in the year receive additional coaching, practice, and competitive opportunities, further enhancing their skills and performance. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where early success leads to more opportunities for development, perpetuating the advantage.

So sometimes we just do not have enough luck to head start and compete.

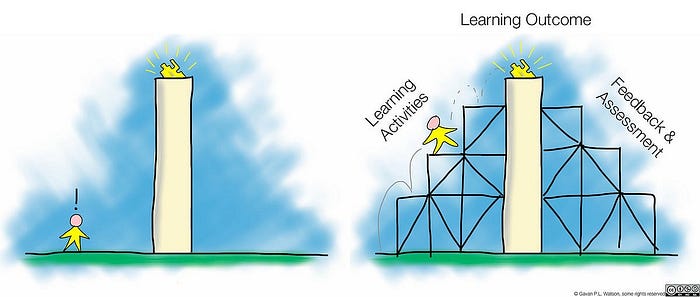

4. Lack of Progress #

Hitting a wall or plateauing in skill development is a common experience that can lead people to abandon their learning endeavors prematurely. They feel their ceil is reached while they probably need a better learning strategy. Overcoming a plateau often requires learners to reassess their approach and adopt new strategies to break through barriers. This might involve seeking out alternative learning methods, experimenting with different techniques, or getting creative with practice routines. Having access to more experienced mentors or coaches can provide invaluable guidance (or scaffolding) and support during times of plateau.

Scaffolding that helps overcome learning obstacles ( Gavatron on Visual hunt / CC BY-NC-SA)

In Anders Ericsson’s book Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, he discusses the case of a person attempting to memorize a sequence of numbers. The individual is given the task of memorizing a long sequence of numbers, such as a random string of digits. Initially, they struggle to recall the sequence accurately despite repeated attempts. The individual encounters obstacles in memorizing the sequence due to limitations in their existing retrieval strategies. They may rely on rote repetition or simple mnemonic devices, which prove ineffective for retaining the information over the long term. To overcome these obstacles, the individual experiments with different retrieval strategies to find one that works more effectively. This could involve chunking the numbers into smaller groups, creating meaningful patterns or associations, or using visualization techniques to aid recall. After discovering a new retrieval strategy that resonates with them, the individual experiences improved performance in memorizing the sequence of numbers.

Finding a new strategy seems daunting. We believe the next step is out of reach and we feel overwhelmed by the challenge. Not everyone has enough persistence to keep trying despite constant failures and lack of progress.

Conclusion #

The concept of talent can sometimes create the perception that certain abilities or domains are only accessible to a select few who are naturally gifted. This can be demotivating for individuals who believe they don’t possess those innate talents.

Children who are unable to “discover” their talents often become demotivated and suffer from low self-esteem. How talent is framed and discussed with children can have a profound impact on their mindset, motivation, and opportunities for growth. By promoting a growth-oriented perspective that emphasizes deliberate practice, effort, and inclusivity, we can support children in developing resilience, a love of learning, and the belief that they can achieve success in various domains through dedication and perseverance. However, we must be aware that the environment and luck (your life context) also can influence the learning path.

If you want to dive deep into the topic I strongly recommend Anders Ericsson’s books and papers. Here you also have other articles that similarly touch on this issue:

- https://www.ethanhein.com/wp/2015/talent-considered-harmful/

- https://evanbishopwriting.com/deliberate-practice-and-why-we-should-stop-saying-the-word-talent/

- https://www.aulexic.com.au/i-hate-talented/

Update 2024–09–04: The following article is a refinement of the ideas introduced in the above post: