Nintendo Completely Sat Out the Video Game Graphics Wars. It’s Winning Anyway. Sherwood News

Nintendo completely sat out the video game graphics wars. It’s winning anyway. - Sherwood News #

Excerpt #

What Nintendo lacks in fancy pixels, it makes up for in dopamine. That’s why it basically prints money.

When you’re immersed in a game like “Cyberpunk 2077,” it’s easy to get lost in its realism.

As you run around the crowded streets of Night City, you notice the reflections of the city lights and neon signs in the puddles when it rains. Even the complexion and texture of a character’s skin are enamoring. At full power, the game, created by CD Projekt Red, is a graphical marvel. It’s also a symbol of a decades-long arms race between the biggest video game companies to make things look as real as possible.

And then there are Nintendo games.

Take 2022’s “Pokemon Scarlet” and “Pokemon Violet” on the Nintendo Switch. Despite being the latest releases in a legendary franchise, in terms of its graphics they could’ve easily been published 15 years ago. It’s a perfect example of how, sometimes to the frustration of gamers, Nintendo seemingly refuses to step into the present day. None of its flagship games really compete with the rest of the industry’s optical experiences. The graphics of games like “Red Dead Redemption 2,” “Starfield,” and “The Last of Us: Part II” are decades ahead of Nintendo.

A screenshot from “Cyberpunk 2077.” (Photo courtesy of CD Projekt Red)

But here’s the thing: Nintendo doesn’t have to catch up, nor does it want to.

“Pokemon Scarlet” and “Pokemon Violet” sold 10 million copies during their launch weekend alone. According to IGN, Nintendo is responsible for three of the top five bestselling video game consoles of all time. Its characters — Mario and Luigi, Link and Zelda, Pikachu and Ash — have defined and are constantly redefining the industry.

Nintendo is a money machine. It’s been raking in more than $10 billion in revenue (more than 1.6 trillion yen) annually for the past several years, and its profits have grown sharply, topping out at about $3.3 billion in the fiscal year ended March 2024. For comparison, in its latest fiscal year, Sony’s gaming division generated $29.1 billion of revenue and an operating profit of nearly $2 billion. Nintendo posted $11.4 billion of revenue and an operating profit of $3.6 billion.

On a recent earnings call, Nintendo doubled down on its volume and longevity strategy, saying: “to convey the appeal of Nintendo Switch, we try to not only put one system in every home, but several in every home, or even one for every person.”

Right now, gamers and investors alike are waiting anxiously for Nintendo to announce the sequel console to the Switch, which is in its eighth year on the market. The company says it will make the announcement by the end of March 2025. That could put some pressure on the company’s sales in the immediate future, but analysts at Wedbush Securities say they “remain fans of Nintendo and its management team’s track record of outstanding execution in recent years.” They expect the stock to go up 16% in the next year.

As one X user hilariously put it:

how is Nintendo still dog walking the rest of the gaming industry with a 7 year old android tablet

— emblasteon (@emblastoons) June 18, 2024

It’s a good question. Even if a studio’s aim isn’t “realism” — as is the case with games like “Horizon: Forbidden West” and “Detroit: Become Human” — gamers still love a spectacle. We like to see the boundaries of computing being pushed further, especially if such an experience is coupled with great storytelling and gameplay mechanics. Nintendo doesn’t seem as interested. It’s the only gaming company that doesn’t care to also be a tech company.

According to NYU Professor Joost van Dreunen, it’s more accurate to look at Nintendo as a toy company rather than a gaming one. “If you look at Nintendo as a company, it’s over 100 years old,” Van Dreunen, the author of “One Up: Creativity, Competition, and the Global Business of Video Games,” told me.

“It originally started as a trading-card game company,” he said, “and over the years really just identified itself as a toy maker. So everything that they do is colorful, it’s accessible, it’s fun. It’s very easy to get into. Maybe not necessarily easy to master, but it’s easy to get into their games.”

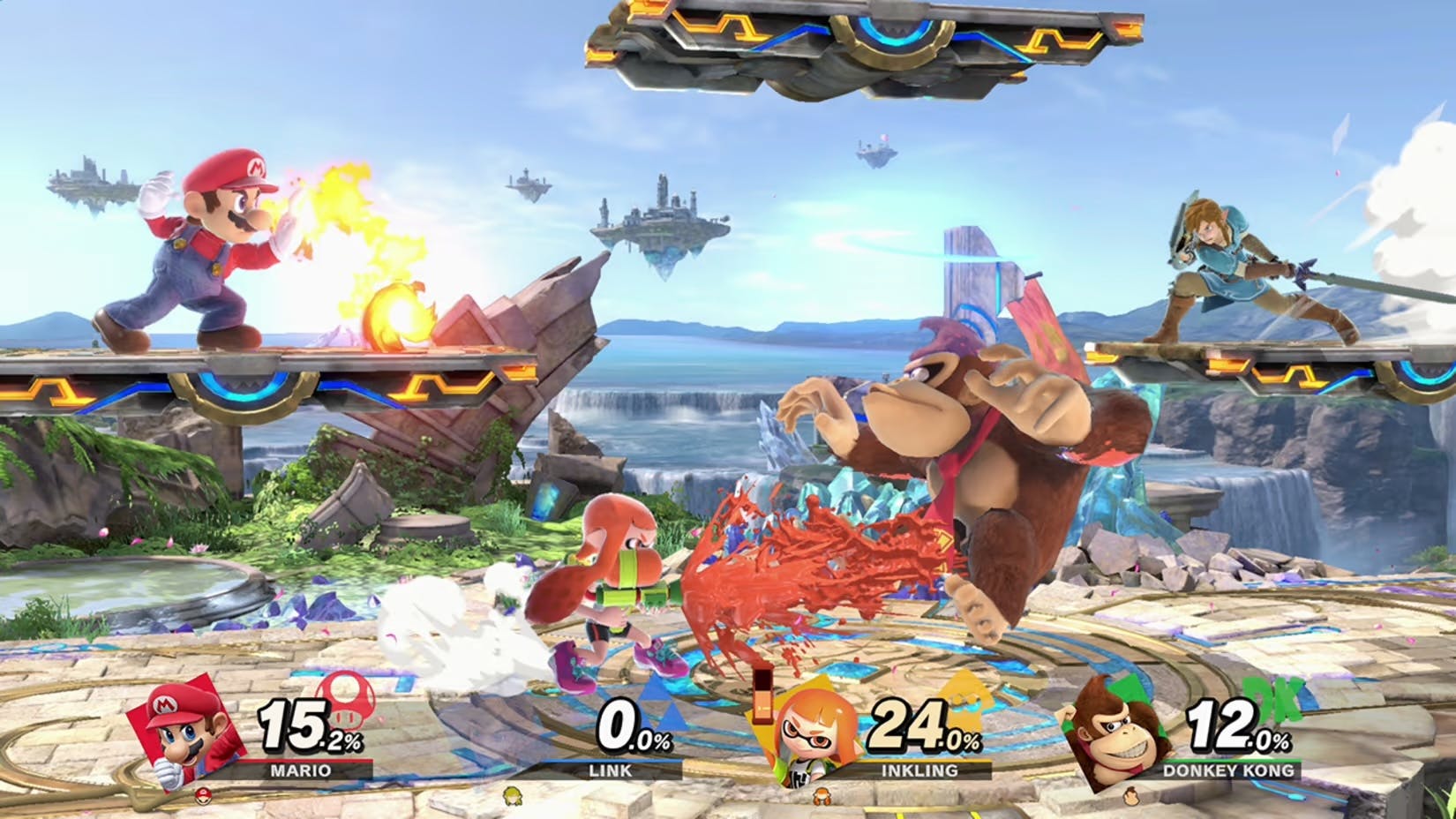

Nintendo’s “Super Smash Bros.” franchise is the best example of this concept. Anyone can pick up the controller, choose one of many characters, and have a blast fighting their friends. It’s a colorful game with lots of joy and surprises.

Gamers play the video game ‘Super Smash Bros" during Paris Games Week in 2019. (Photo by Chesnot/Getty Images)

But beneath the surface is a world of competition that can only be described as insane. Each character has its own set of fighting moves, and the time it takes to complete each move varies. When you string some of these moves into longer combinations, the possibilities increase exponentially.

There are hundreds, maybe thousands, of ways to exploit your opponent and vice versa. I consider myself decent at the game — maybe as good as the average player — but nowhere near as talented as some of my friends who have honed their skill down to a matter of literal frame rates. I’m not exaggerating: they know how many frames of video it takes to pull off certain moves, which allows them a level of precision that I can only dream of.

“If you play ‘Super Smash Bros.,’ you kind of get it right away. But to get good at it takes a long time, and it has a deep sense of maturity in its gameplay mechanics and the quality that it delivers,” Van Dreunen said.

Nintendo

Instead of innovating on technology, Nintendo has mastered the dopamine-reward system. You get out of a Nintendo game exactly what you put into it. The actions you take in their games feel good and natural.

“Mario is a really good example of a brand that’s been consistent, but the success of Mario has nothing to do with the fact that he’s now a higher pixelated model,” Van Dreunen told me. “What’s important about Mario’s success is the fact that the games are always centered around the same gameplay mechanics that evolve over time and become more complex… I would argue that it’s much harder to do that. Throwing technology at it as a solution is really the easy way out.”

The misleadingly basic gameplay mechanics of today’s Nintendo games are the very same that launched the company into the sales stratosphere in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Press A to jump. Press B to punch. And if you press A to jump and then press B in the air, you perform a separate third move. That is to say that the B button behaves differently depending on the circumstance the character is in. It sounds remedial today, but the mechanics were so successful back then that entire franchises were born out of copying it.

Enter “Sonic the Hedgehog” in 1991, SEGA’s answer to the “Super Mario” franchise. A great series of titles on its own, you play as a little blue speedster who races through various “stages,” during which you must also perform the sort of platforming mechanics that the Mario games made so popular. Press A to jump onto a ledge. Press B to attack. SEGA’s effort was different enough to make huge waves in the gaming industry — and is responsible for my personal favorite game of all time, “Sonic the Hedgehog 2” — but it clearly wouldn’t exist were it not for Nintendo’s influence. This pacesetting is what Van Dreunen suggested as evidence of Nintendo’s long-lasting dominance into the 2020s.

“I think the entire console industry is looking to Nintendo to see when it’s going to announce its next move, to kind of set the agenda for everything that follows… because they are the backbone of that space in many ways,” Van Dreunen said.

The former trading-card company is a front-runner in the industry in other ways. What Nintendo lacks in graphics capabilities, it makes up for in the creative formats through which it asks the audience to play its games. Ever since the Nintendo Wii was released, with its remote controls and motion sensors, suddenly just about anyone could be a gamer.

“It goes to this larger agenda of Nintendo sort of refusing to always be at the forefront of technological capacity,” Van Dreunen said. “It’s just infrared remotes, right? It’s not that big of a deal. But what it allows you to do, in my case, is play tennis with your mother-in-law… It sort of opens the living-room experience up to a broader range of different players, and it’s accessible enough that everybody can use a Wiimote to play bowling. It’s not that hard, right? So it makes the gameplay more accessible.”

Sure enough, Sony and Microsoft responded to the Wii remote with their own motion-sensored devices: the PlayStation Move and the Xbox Kinect, respectively. But generally, the games these consoles host aren’t motivated by the prospect that anyone could play them. Players must go into new PlayStation and Xbox titles equipped with knowledge acquired from years of prior gaming experience. It’s what I call “video game literacy,” and I ran into this issue when my partner became interested in gaming and tasked me with finding her a good entry point.

For fun, I would create save files for her in games like “Cyberpunk 2077” or “Starfield,” but I quickly realized that the barrier to entry in these games was simply too high. Because she was new to gaming, she didn’t have the instinct to, say, investigate a crack in a wall or look for a key when a door was locked. “Ah, it’s locked, so this isn’t the right path,” she would quite understandably say. The myriad menu screens, item-crafting mechanics, and map functions made no sense to her, and because the games are made for players who already have experience, the assist features did little to nothing to help guide her along.

That’s when I thought about giving her a game that I played early in my own journey, and gave her a copy of 2000’s “Paper Mario.” It was like magic. The game prompted her to do something with hints and nudges, and then she remembered to do it the next time she was faced with a given obstacle. That experience immediately translated to newer titles like “Hogwarts: Legacy” and “It Takes Two,” and voila, a gamer was born.

Amid tantalizing rumors about Nintendo’s follow-up console, Van Dreunen told me the company has only itself to compete with.

“It will probably be an underwhelming device compared to the PlayStation 6 and whatever Microsoft has in store next, because it won’t try to be at the forefront of technological innovation. But it will set the tone for what’s next. And I think as the games industry is now catering to a mainstream audience, Nintendo only has upside.”

Pikachus dance in a parade last year in Japan. (Photo by Stanislav Kogiku/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Accordingly, one of the company’s upcoming titles is “The Legend of Zelda: Echoes of Wisdom,” a new edition to perhaps the most storied franchise in gaming. Players will take on the role of Zelda this time, not her perpetual savior, Link, and make their way through the game by conjuring “echoes,” or imitations of items and creatures you encounter in the world. These echoes, which can take the form of anything from a table to a monster, will allow you to defeat enemies and solve the puzzles that are foundational to every Zelda game. It’s another fresh take on a staple, and the kind of new iteration that Van Dreunen said is pivotal to Nintendo’s success, and dominance.

Nintendo is “able to navigate these franchises through a period of change to a period of technological changes and still maintain the same brand values and same expectations of the audience, and surprise them on top of that,” he said. “That’s a much harder thing to do than adding more chips and more storage capacity and better battery life to things.”

Manny Fidel is a producer and writer based in Brooklyn, New York.