How to Create Software Quality. Irrational Exuberance

How to create software quality. | Irrational Exuberance #

Excerpt #

I’ve been reading Steven Sinofsky’s Hardcore Software, and particularly enjoyed this quote from a memo discussed in the Zero Defects chapter:

You can improve the quality of your code, and if you do, the rewards for yourself and for Microsoft will be immense. The hardest part is to decide that you want to write perfect code.

If I wrote that in an internal memo, I imagine the engineering team would mutiny, but software quality is certainly an interesting topic where I continue to refine my thinking. There are so many software quality playbooks out there, and I increasingly believe that all these playbooks work in their intended context, but are often misapplied.

I’ve been reading Steven Sinofsky’s Hardcore Software, and particularly enjoyed this quote from a memo discussed in the Zero Defects chapter:

You can improve the quality of your code, and if you do, the rewards for yourself and for Microsoft will be immense. The hardest part is to decide that you want to write perfect code.

If I wrote that in an internal memo, I imagine the engineering team would mutiny, but software quality is certainly an interesting topic where I continue to refine my thinking. There are so many software quality playbooks out there, and I increasingly believe that all these playbooks work in their intended context, but are often misapplied.

For example, pretty much every startup has someone on an infrastructure team who believes that all quality problems can be solved with a sufficiently nuanced automated rollout strategy. That’s generally been true in my experience at companies with a high volume of engaged usage, and has not at all been true in environments with low or highly varied usage. Unsurprisingly, folks who’ve only seen high volume scenarios tend to overestimate the value of rollout techniques, and folks who’ve never seen high volume scenarios tend to underestimate the value of rollout techniques.

This observation is the underpinning of my beliefs about creating software quality. Expanding from that observation, I’ll try to convince you of two things:

Creating quality is context specific. There are different techniques for solving essential domain complexity, scaling complexity, and accidental complexity.

For example, phased automated rollouts don’t help much if there’s little consistency among your users’ behaviors.

Quality is created both within the development loop and across iterations of the development loop. Feedback within the loop, as opposed to across iterations, creates quality more quickly. Feedback across iterations tends to measure quality, which informs future quality, but does not necessarily create it.

For example, bugs detected after software is nominally complete tend to be fixed locally, even if they reveal a suboptimal approach. I’ve seen projects launch using Redis for no reason, which later causes a production incident, just because the developer was interested in learning about Redis and it was too late to rip it out without doing substantial rework.

Those are some nice words. Let’s see if I can convince you that they’re meaningful words.

Defining quality #

Generally I think quality is in the eye of the beholder, but my experience writing for the internet indicates that people will be upset if I don’t supply a definition of quality, so here’s my working direction:

- Software behaves as its users anticipate it should behave

- Software is easy to modify

- Software meets reasonable non-functionality requirements (latency, cost, etc)

There are, undoubtedly, better definitions out there, and feel free to insert yours.

Kinds of complexity #

Managing quality is largely about finding useful ways to deal with complexity. For example, a codebase might be complex due to its size. Complexity in large codebases can be managed by using a strongly typed language, increasing test coverage, and so on.

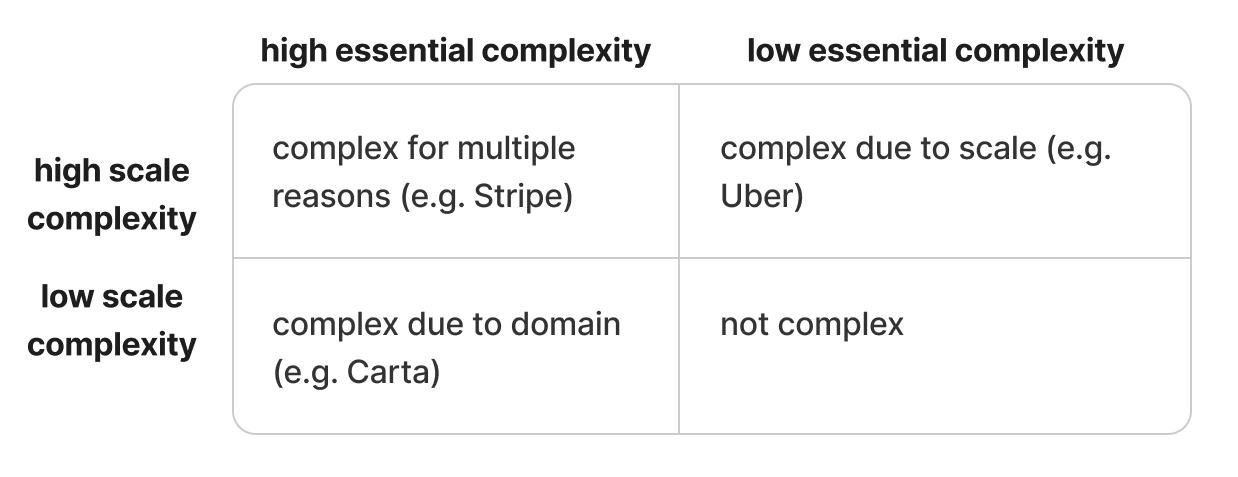

I find it useful to recognize whether complexity is mostly driven by high scale (e.g. you’re performing 10,000s or 100,000s of requests per second) or whether complexity is mostly driven by a complex business domain (e.g. you’re trying to capture the intent of open-ended business contracts into a structured database). I think of the former as “scale complexity” and the later as “essential domain complexity”, extending the phrase from Fred Brooks’ No Silver Bullet.

The third common sort of complexity is accidental complexity. If you’ve used a bunch of different technologies for each part of your product because your team was excited to “try out something new”, then your problems are likely of the accidental variety.

Creating quality is context-specific #

My experience is that most folks in technology develop strongly-held opinions about creating quality that anchor heavily on their first working experiences. For example, many folks whose early jobs included:

- high-volume websites or APIs believe that automated rollbacks driven by production metrics are a fundamental mechanism to prevent a low quality release from impacting users. However, in a domain with infrequent, complex and precise user actions–very much the case for Carta’s domains of fund accounting and managing cap tables–those techniques are less helpful. They certainly might prevent some issues, but they’d fail to prevent many others because the volume of user actions is insufficient to test the full cardinality of potential configurations

- high-volume consumer-facing applications believe that A/B testing can determine quality. However, Michelle Bu’s Eagerly discerning, discerningly eager discusses how many tools for validating quality don’t apply effectively when it comes to API design. She proposes friction logs as a replacement for user interviews, pilot programs as a replacement for beta testing, and dogfooding as a replacement for A/B testing

- highly critical and narrow problem spaces might benefit from multiple heterogeneous implementations voting to determine the correct answer in the face of software errors, as described in Gloria Davis’ 1987 paper An Analysis of Redundancy Management Algorithms for Asynchrous Fault Tolerant Control Systems. However, maintaining and verifying multiple heterogeneous implementations would be extremely costly for broad problem domains that are expected to change frequently (the typical problem domain for startups)

The key observation here is that there’s no universal solution that “just works” across all problem domains. Even the universally accepted ideal of “have a highly conscientious and high-context engineer do it all themselves” isn’t a viable solution in an environment where the current team is too small for the desired volume of work.

Generally, I think your approach to creating quality will vary on these dimensions:

- Essential domain complexity – a problem domain with few workflows and conditions can often be validated by looking at user usage (e.g. an application like Instagram, TikTok or Calm has very few workflows and conditions in the software, although the variety of mobile devices they need to run on does increase essential complexity). A problem domain with many workflows or many conditions requires a different approach, which might range from simulating usage to formal specification.

- Scalability complexity – sufficient user traffic solves a lot of problems. At Calm, Uber or Stripe, the scale was high enough that errors were immediately visible in operational data, even with an incremental rollout strategy. At Carta, that would only be true in the case of an exceptionally broad error (a category of error that’s relatively straightforward to catch with automated testing), given the different user usage patterns.

- Maturity and tenure of team – a team with deep context in the problem domain is able to drive quality with fewer distinct roles, more individual empowerment, and less structured process. A team with high turnover generally leans on more defined roles where it’s easier to quickly develop context. Similarly, a team that feels accountable for high-quality will behave differently than a team that feels otherwise.

To develop my point a bit, let’s think about two combinations and how we’d approach quality differently:

- Low essential complexity problem domain, high traffic, and deep team context – a thorough test suite will go a long way to validating the expected behavior, and the team has enough familiarity with the problem space for engineers to effectively test as they implement. If you do miss something, an incremental rollout mechanism, using production operating metrics to pace rollout, will probably prevent testing gaps from significantly impacting your users

- High essential complexity problem domain, low traffic, and limited team context – designing effective test suites is a challenge because of your team’s limited context and the complex problem space. This means you may need dedicated individuals working on testing frameworks to encapsulate domain context into a reusable testing harness/framework rather than relying on individual team member’s context. It might also mean a focus on highly defined types that codify parts of the domain context into the typechecker itself rather than depending on the awareness of each individual writing incremental code. Incremental rollout mechanisms are unlikely to catch issues missed by testing, because conditions differ enough across users that even a small number of catastrophically failing users are unlikely to meet the necessary thresholds

These are radically different approaches, and if you naively applied the solution for one combination to another, you will generate a lot of motion, but are unlikely to generate much impact. Once you’re aware of these combinations, you can start to see what sort of techniques are adopted by folks working on similar problems, but the awareness also helps you start to build a model for creating quality across various circumstances.

Is tolerance for error an important dimension? #

Before developing a model for reasoning about creating quality, a few comments on “tolerance for error.” I think many people would argue that your tolerance for error is an important dimension in determining your approach to creating quality, but to be honest I haven’t found that a useful dimension.

For example, if you tell me that you highly prioritize quality at your company, and that’s why you have a very large quality assurance organization, or a very formal verification process, my first response would be skepticism. Quality assurance teams are extremely useful in many scenarios. Formal verification processes are also very useful in many scenarios. However, neither is universally ideal, and both can be done poorly.

In my personal experience, the highest quality organizations are those with detail oriented executives who actively inspect quality in their teams’ work. That executive-driven inspection elevates quality into first-tier work done by their leadership, and so on down the chain. In those organizations, there are often teams that build quality assurance tools, but those teams support quality rather than being directly accountable for it.

Others’ personal experiences will be the opposite, and that’s entirely the point: I’ve seen low tolerance for error drive a wide variety of different approaches. Similarly, I’ve seen organizations with a high tolerance for errors both go heavy on quality assurance and heavy on engineer-led quality. As such, I don’t think this is an important dimension when reasoning about creating quality.

Iterating on a model #

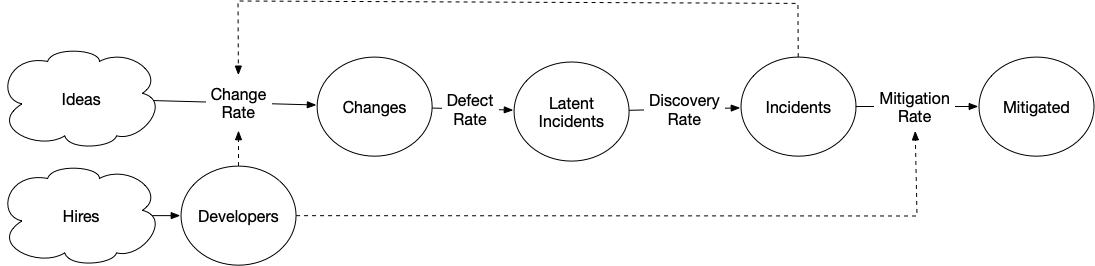

My model of creating quality started as a model for reliability.

There’s a lot to like about this model, I think the idea of “latent incidents” is a particularly useful one, because it acknowledges that even if you improve your quality practices, it may take a very long time to drain the backlog of latent incidents such that you actually feel like you’ve improved quality. I imagine many teams actually solve their quality problem but accidentally abandon their successful approach before they drain the backlog and realize they’ve solved it.

I made the above model at a period when I was almost entirely focused on accidental complexity from a sprawling codebase and scaling complexity from an increasingly large volume of concurrent usage. Because of that focus, I spent too little time thinking about the third source of complexity, essential domain complexity.

What I’d like to do here is to develop a model that incorporates both the insights of my prior model and also the fact that essential domain complexity has been the largest source of quality issues in my current and prior roles at Carta and Calm.

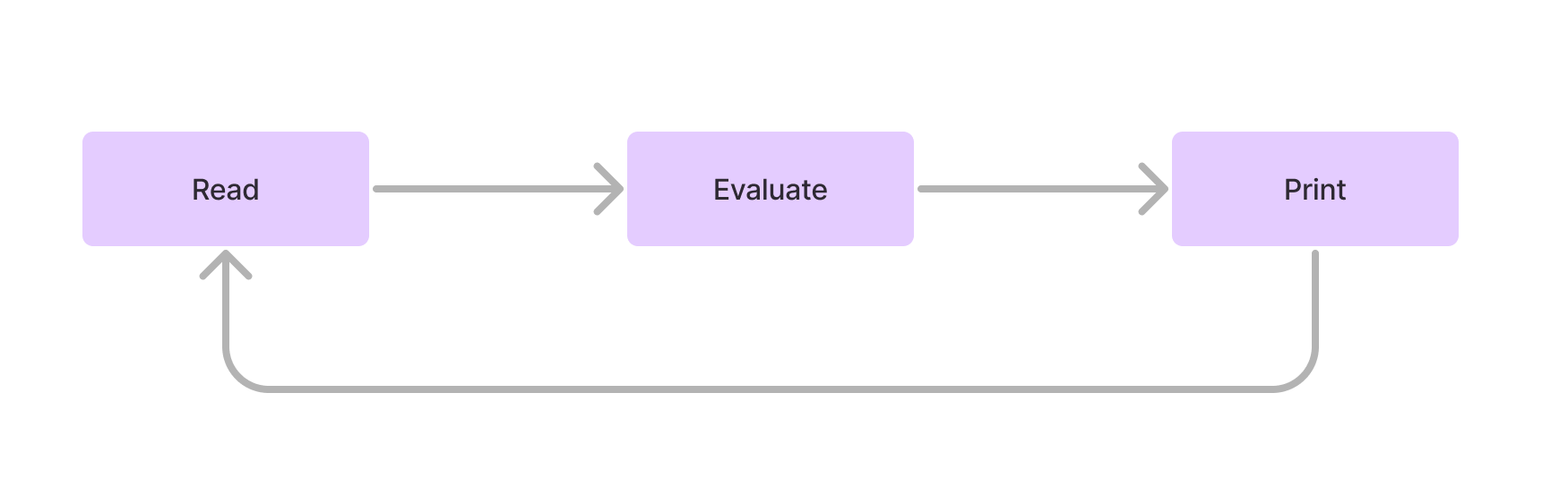

I think it’s useful to start with the smallest possible loop for iterating on software, the Read Eval Print Loop (aka REPL), first popularized in 1964.

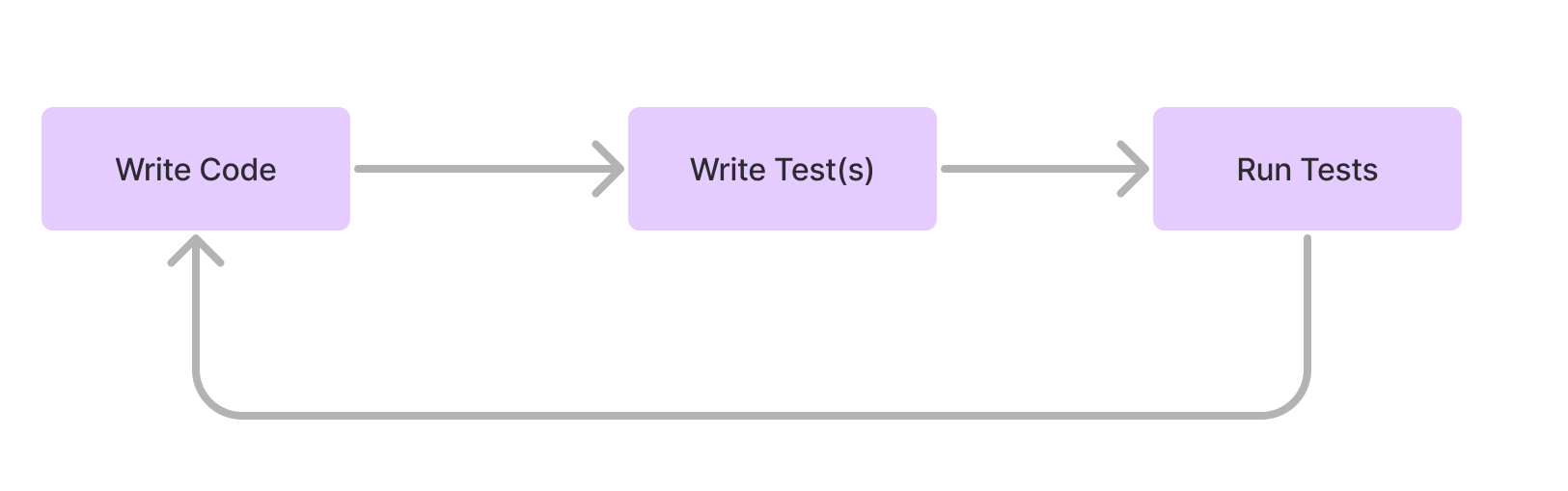

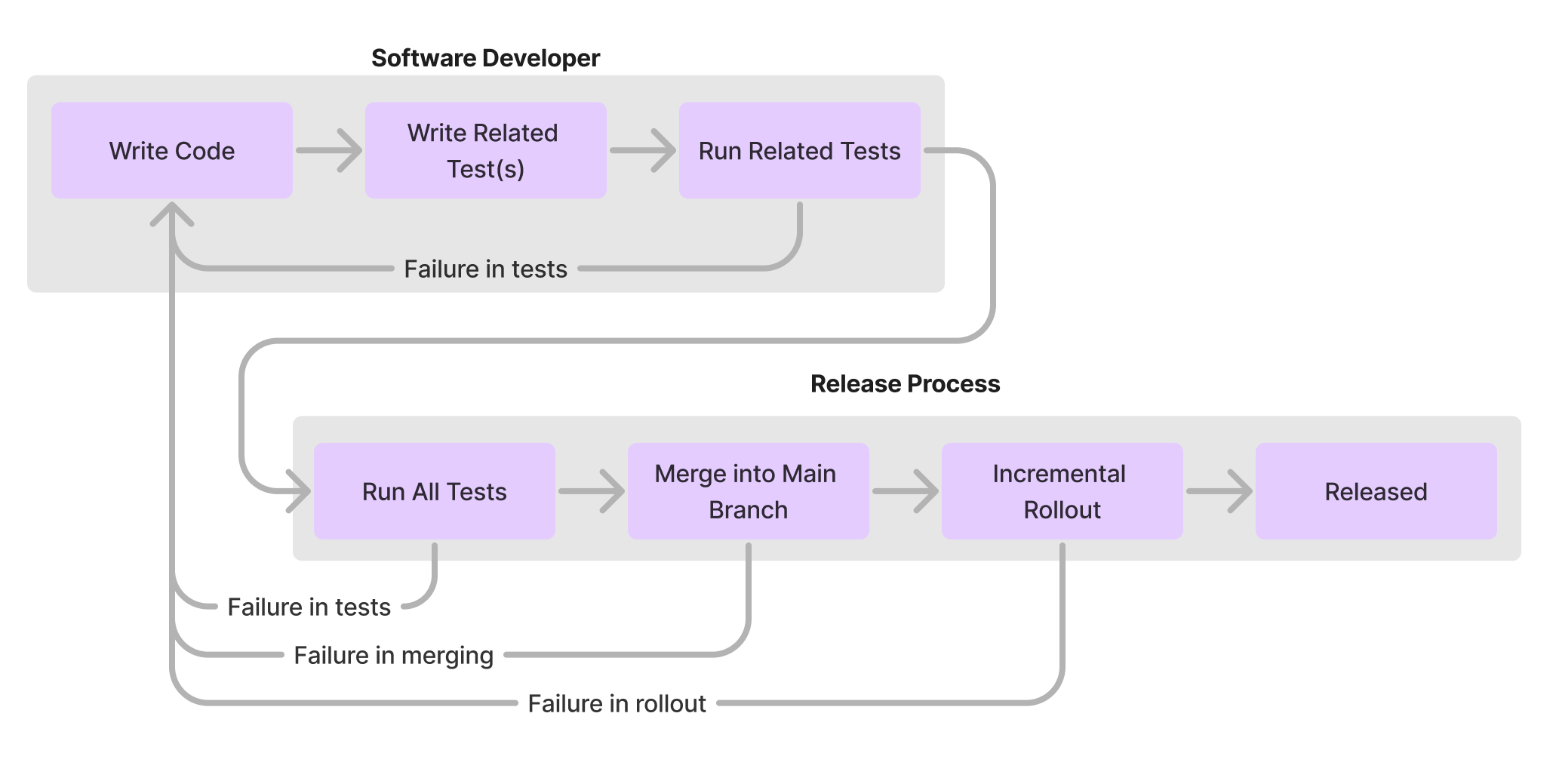

Not much modern development is done directly in a REPL, but developer-led testing provides a very similar loop, with a single developer looping from writing a piece of code, to writing tests for that code, to running the tests, to addressing the feedback raised by those tests.

Now let’s try to introduce the fact that this tight iteration loop is just one phase of shipping software. After writing software, we also need to release that software into production. After all, as Steve Jobs said, real artists ship!

In particular, it’s worth noticing the loops that occur within one node versus the loops that occur across nodes. It’s significantly faster to iterate within a node than it is to iterate across nodes.

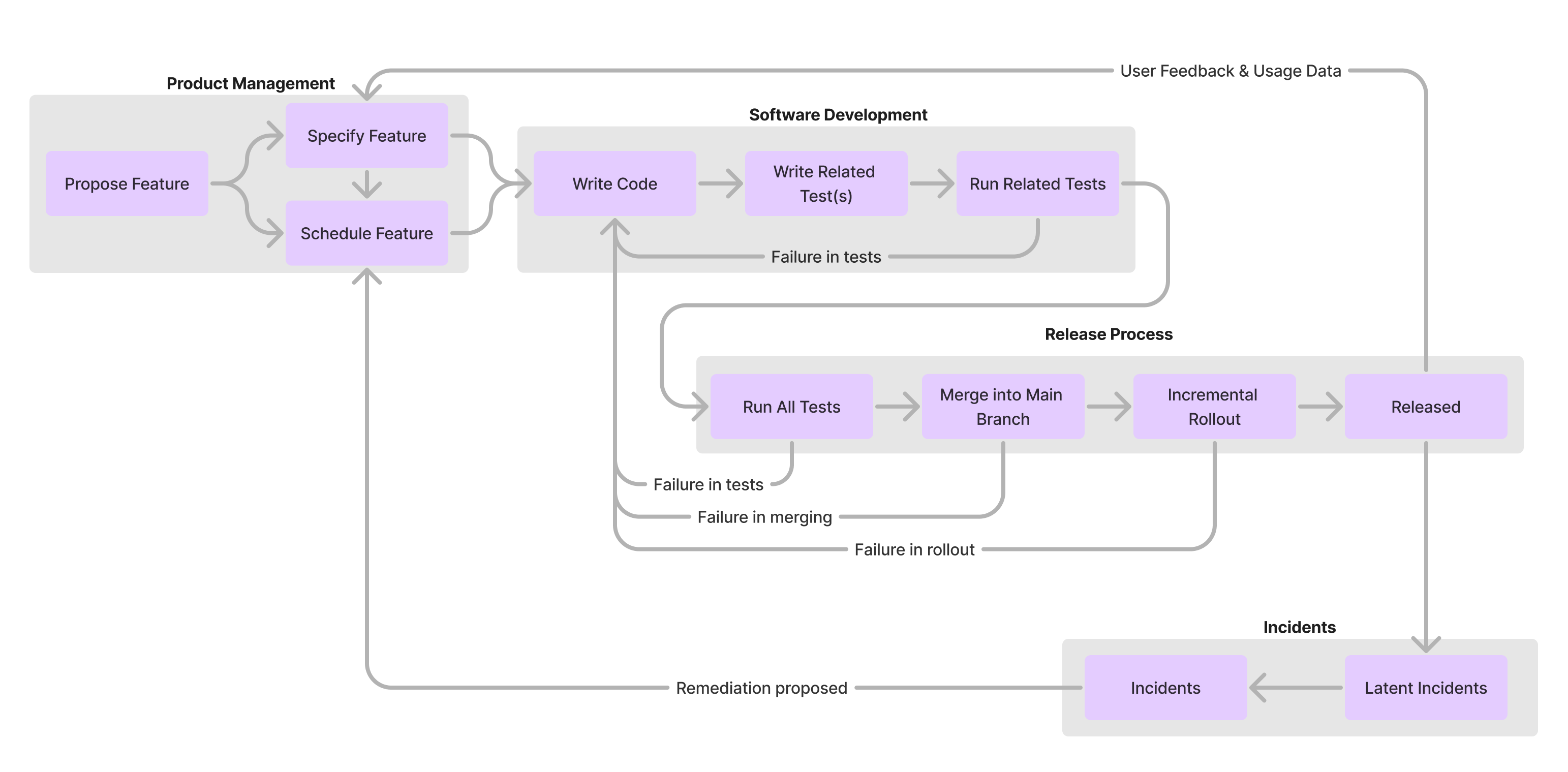

While we’re starting to get a bit closer, but we’re missing a few key things here to reason about the quality of our code. First, even after releasing code, there can be a defect rate where the implementation doesn’t wholly solve the domain’s essential complexity, such that there is a latent defect. Alternatively, there might be an emergent issue in production caused by either accidental complexity (e.g. sloppy environment setup) or scaling complexity (e.g. unexpected traffic spike).

Second, sometimes engineers don’t understand the feature they’re trying to implement, even when they’re trying hard to do so. This might be because they’re new to the team and it’s a complex problem space. Or it might be because they had a miscommunication with their product manager, who is responsible for defining the required functionality.

This model starts to get interesting! The first thing to note is just how delayed the feedback is from writing software to rewriting software if that feedback requires releasing the software. If the handoff of specification from product to engineer goes awry, it may take weeks to detect the issue. This is even more profound in “high cardinality” problem domains where there’s a great deal of divergence in user usage and user data: it may take months or quarters for the feedback to reach the developer about something they did wrong, at which point they–at best–have forgotten much of their original intentions.

Like any good model, you can iterate on it endlessly to capture the details that are most interesting for your situation:

- If you’re mostly focused on scalability complexity, then the release process is likely particularly interesting for you.

- If you’re focused on accidental complexity, then proactive and reactive controls on software design–mechanisms that gate access to and departure from the software development cluster–would be the most interesting such as architecture reviews or verifying properties within pull requests before merging them.

- If you’re focused on essential domain complexity, then you’re focused on either feature specification or the software development feedback loop. Techniques to address might vary from embedding new hires onto teams with high context to requiring pull requests be reviewed by a domain expert, to developming a comprehensive test harness that makes it easy for developers to test new functionality against the full spectrum of unusual scenarios.

The best way to get a feel for any model is to experiment with it. Delete pieces that aren’t interesitng to you, add pieces that seem to be missing from your perspective, and see what it teaches out.

Measurement contributes to (!= creates) quality #

One important observation from this model is that errors detected in production, or even in release, are much harder to address effectively than errors detected by the engineer writing the software initially. I think of detecting errors after the software engineer handoff primarily as measuring quality rather than creating quality. My reason for this distinction is that any improvement from this measurement occurs in a later iteration of the loop, as opposed to within the current loop.

I think this is an important distinction because it provides the vocabulary to discuss the role of software engineering teams and the role of quality assurance (QA) teams.

Software engineering teams write software to address problem domain and scaling complexity. Done effectively, developer-led testing happens within the small, local development loop, such that there’s no delay and no coordination overhead separating implemention and verification In that way, developer-led testing directly contributes to quality in the stage that it’s written.

QA teams write software (or run manual processes) to measure the quality of that software in the problem domain. QA-led testing happens in a distinct step, even if that step occurs concurrently, and as such the software’s initial design is not influenced by QA tests. That influences only occurs when the quality loop next repeats.

This is an important distinction, because the later in development an issue is detected, the more likely it is that it’s addressed tactically rather than structurally. Quality issues detected late are more likely to drive improvement in specific correctness (fix the test case) rather than in fundamental approach (redesign the architecture). It also doesn’t mean that QA-led testing isn’t valuable, it’s very valuable for managing the sort of cross-feature bugs that an engineer with narrow context would not know to test for, but it does mean that developer-led testing of their current work creates quality sooner and in ways that QA-led testing does not.

Trying to ground this observation in something specific, think about John Ousterhout’s idea of defining errors out of existence from Philosophy of Software Design. That principle argues that you can eliminate many potential software errors by designing interfaces which prevent the error from occuring. For example, instead of throwing an error when I attempt to delete a non-existent file, it might simply confirm the file does not exist. QA-led testing might ensure that the function throws the error only at the correct times, but it would only be developer-led design (potentially including developer-led testing or dogfooding) that would allow the quick iteration loop that supports changing the interface entirely to define that error out of existence.

As an aside, this is more-or-less the same point I tried to make in my contribution to GitHub ReadME, but there I was focused on incident response. Measuring prior incidents and instances of incident response are an input to improving future incident response, but do not directly improve reliability: only finishing projects that increase reliability does that, and investing more into measurement when you aren’t completing any projects doesn’t solve anything.

What should you do? #

The intended takeaway from all this is exactly where we started in the introduction: creating quality is context specific. Be wary of following the playbook you’ve seen before, even if those playbook were tremendously successful. They might work extremely well, but they often don’t unless you have a useful model for reasoning about why they worked in the former environment.

Throughout this piece, I’ve tried to explain and references ideas as I’ve invoked them, but here are some of the materials that might be worth reading through if this is an interesting topic to you:

- “Define errors out of existence” is an idea from John Ousterhout’s Philosophy of Software Design, and described with some great examples in this page from the TCL Lang wiki

- The distinction between essential and accidental complexity, discussed in Fred Brooks’ No Silver Bullet from Mythical Man Month is a valuable dimension for reasoning about complexity (and consequently, quality)

- Eagerly discerning, discerningly eager is a great piece from Michelle Bu that discusses how API design is distinct from many other sorts of product design (e.g. can’t use A/B testing, but can work with other companies as design partners)

- Kent Beck’s Tidy First? discusses a number of strategies for addressing accidental quality issues within a codebase, mostly those caused by inconsistent implementations across a large codebase. I wrote up some notes on this book a while back

- Reclaim unreasonable software captures my thinking about creating quality in a codebase that has become challenging to reason about. In this piece’s vocabulary, it’s most interested in solving accidental and scaling complexity

- Manage technical quality is a chapter from Staff Engineer which describes many of the tools you can use to improve quality. Most of the discussion here is composition-agnostic, e.g. useful techniques that might or might not apply to various compositions, and certainly you can use the quality model to evaluate which might apply well for your circumstances

- Domain-Driven Design Distilled by Vaughn Vernon is a good overview of domain-driven design, which is an approach to software development that applies particularly well to working in problem domains with high essential complexity

- Practical TLA+ by Hillel Wayne is a useful introduction to formal specification, which is a topic that not many software engineers spend time thinking about, but an interesting one nonetheless

- Building Evolutionary Architectures by Ford, Parsons, Kua and Sadalage has a number of ideas about guided evolution of codebases (here are my notes on the 1st edition). Generally composition-agnostic in their recommendations

These are all well worth your time.