Engineering Principles for Building Financial Systems

Engineering Principles for Building Financial Systems #

Excerpt #

Best practices and principles to create accurate and reliable software based financial systems.

Accounting hasn’t really changed in the past couple of hundred years. Despite this, there is a lot of confusion around the right way of building software for financial systems.

In this post, I’ll share lessons from my years working on financial systems at big tech companies. Our focus will be building an accounting system, but the principles apply to more general financial systems as well.

This post will go over the following

Basic financial definitions relevant to the post

High level goals of an accounting system

Engineering principles to achieve those goals

Best Practices

Definitions #

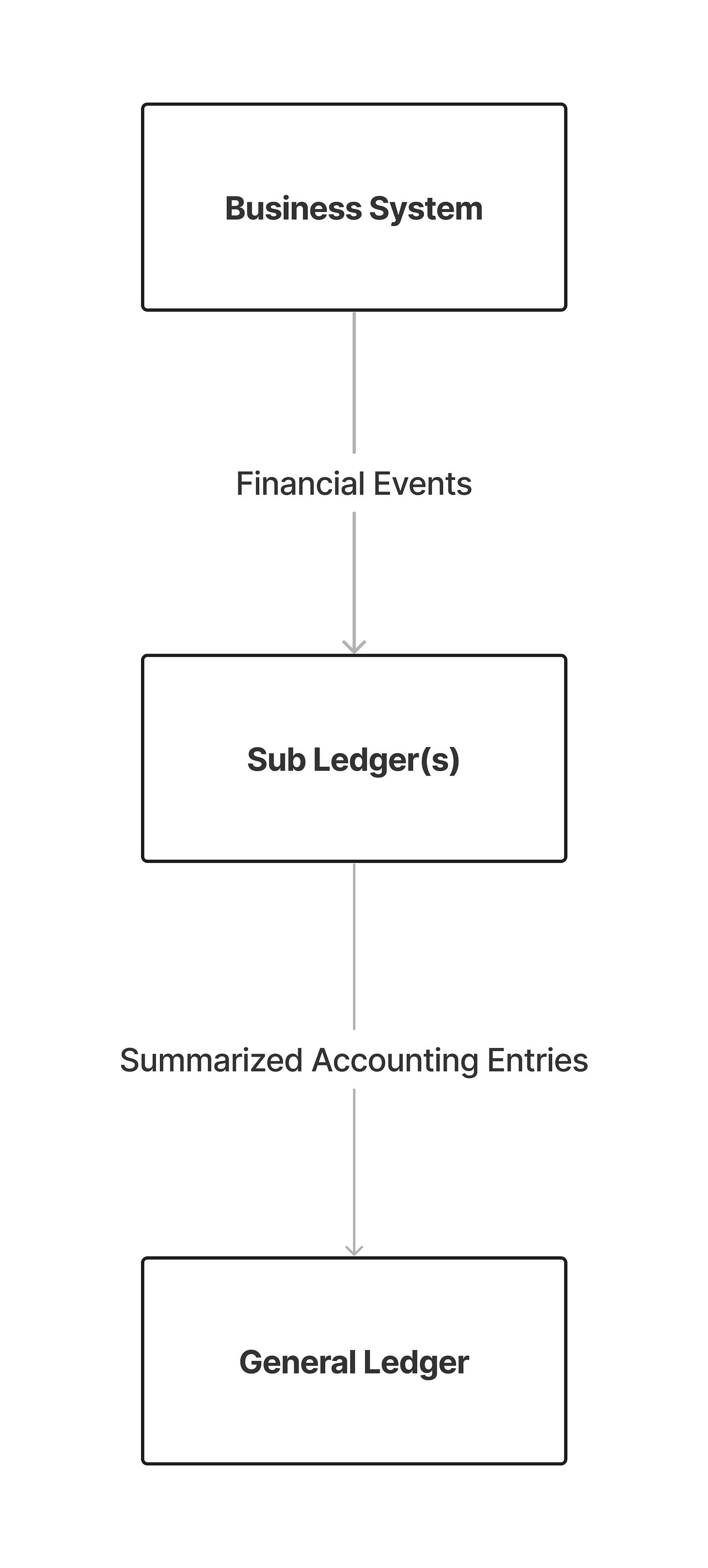

General Ledger (GL): The primary accounting record of the company, summarizing all financial transactions over a specific time period. You can think of this as an aggregation of it’s corresponding sub-ledgers.

Sub-ledger: Contains detailed information about all individual transactions related to a specific GL. Records in the sub ledger will have much more granular data then the general ledger, like who the specific customer is, specific line items in an order, etc. The difference in data between the sub-ledger and GL will depend on the type of business and volume of data you are working with. Some small businesses can get away with not having any sub-ledgers at all, but it is doubtful that they would ever need custom software to manage something that is so low in scale.

Financial Record: This refers to the general ledger and sub-ledgers.

Material: Materiality refers to whether misstatement of information in your financial statements would impact a reasonable stakeholder’s decision making statements. Note that this definition is somewhat ambiguous by design, as different businesses have different materiality thresholds. For example what might be material for a business making $250,000 of revenue per year, will not be material for a business making $1 billion in revenue. From a design perspective, the main value of this concept is to classify different categories of financial data.

High Level Data Flow #

[

Goals #

The three main goals of your accounting system are to be (1) Accurate, (2) Auditable and (3) Timely.

Accurate #

The financial record needs to reflect the known state of the business. This statement is a little broad and up to some interpretation so I will give some real examples.

If we sell a 10 units of a product that costs $9.99, the corresponding financial records must add up to $99.90. This seems obvious but when you are aggregating thousands (in a lot of cases millions) of transactions, simple summation or rounding errors between systems can cause material inaccuracies.

Wasteman’s Note: People say naming is the hardest problem in computer science, I would say a close second is addition. After working on large scale financial systems for the past few years, I can’t remember how many times the smallest bugs caused large discrepancies in our data. Also don’t get me started on summations over floats. I learned the hard way why you should always use integers.

The financial record also needs to be complete. More specifically, both the sub-ledger and the general ledger are a complete representation of all business activities that occurred at a specific time. If there is an event that occurred but is not in the financial record, than the system is not complete. Note, that this doesn’t imply eventual consistency not acceptable. You just need to know when your data will become complete, to notify stakeholders that data has settled.

Wasteman’s Note: Another surprisingly really hard problem is guaranteeing completeness. As your system scales, data hops between many systems and at each hop data can easily be mutated or dropped by accident.

Auditable #

Very related to accuracy, your financial record must be easily auditable so that stakeholders can detect errors and accurately measure performance of your business. And even if you don’t care, the IRS definitely does.

Timely #

This one depends entirely on your business and it’s specific needs. Small businesses can get away with just dumping all numbers near the end of the month, just in time to close the books. Larger businesses generally want to avoid this, and have a near real time system. This allows them to monitor financials within the month, make decisions based on financial data faster, and reduce the rush to close the month/quarter in the first few days of the month.

But whatever that need is, our accounting system should meet the needs of your business, and whatever timely means to them.

Wasteman’s note: People tend to get lost in conversations about batch vs streaming systems with respect to timeliness a lot. My take is that this isn’t an important distinction to make for most systems. If you care about super low latency cases within seconds to minutes, then this matters. But you would be surprised at how often I hear people arguing about which to do, when the consumer doesn’t need to see updates more than a couple times a day. Just because they asked for it doesn’t mean they need it.

The three main engineering principles your accounting system should abide by are

Immutability and Durability of data

Data should be represented at the smallest grain

Code should be Idempotent

Immutable and Durable #

This allows for auditability, which helps debugging and in turn accuracy. When data is immutable, you have a record of what the state of the system was at any given time. This makes it really easy to recompute the world from previous states, because no state is every lost.

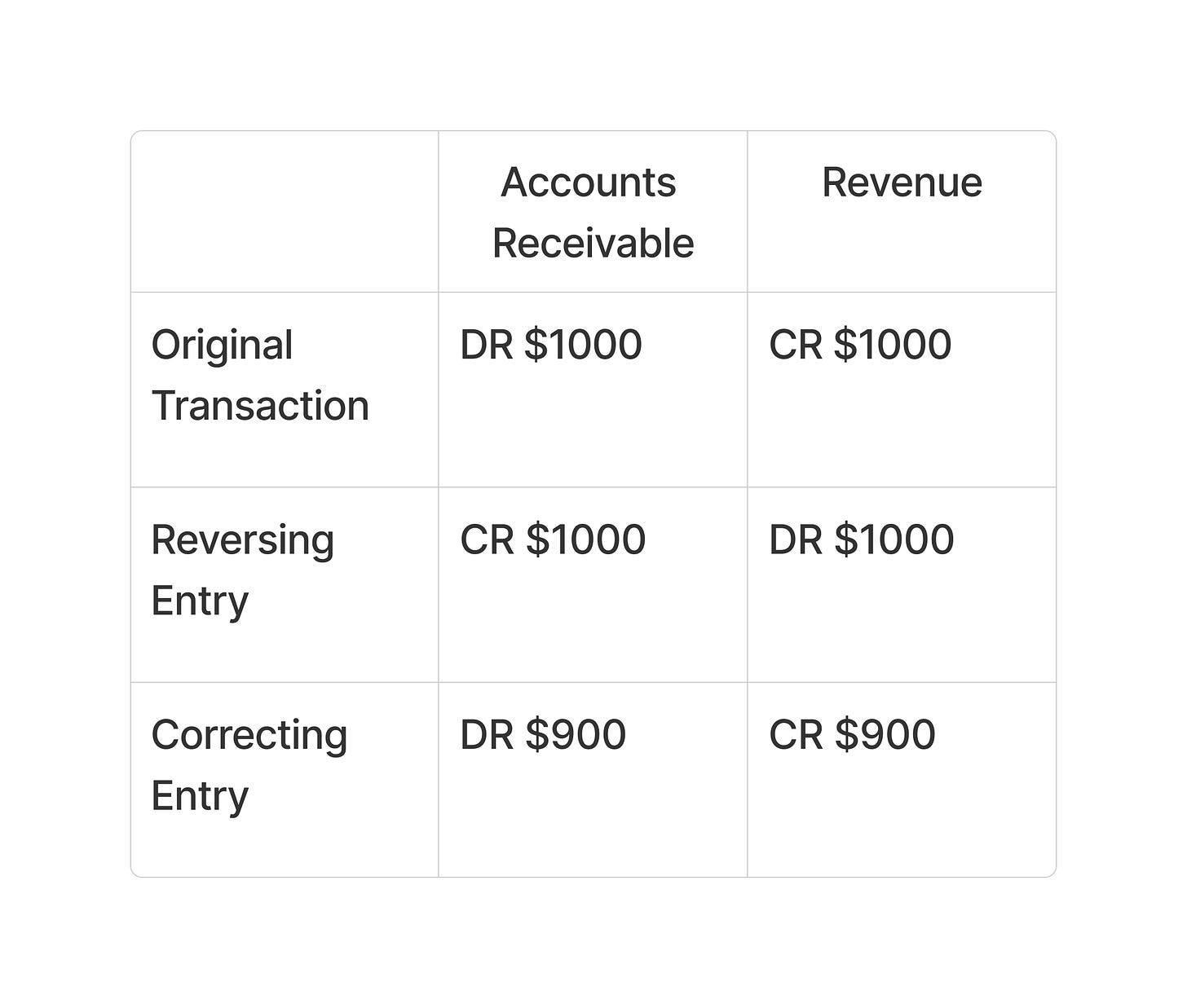

Building on, once data is stated in the financial record it cannot be deleted. Any corrections to the system must be represented as a new financial transaction. For example let’s say your system had a bug and accidentally reported that a service was sold for $1000, when it should have been $900. To correct this mistake, you should first reverse the accounting entries corresponding to the mistake, and restate the accounting entry for the correct amount.

It will look something like this:

[

So you can see that in the financial record, there is evidence that the balance of Accounts Receivable (AR) and Revenue was $1000 at some point, but was corrected later. Even though that balance was incorrect, we want an audit trail of what the balance was at any given moment.

Data recorded at the smallest grain #

Similar to the above principle, this is also critical for enabling a clear audit trail. Even though financial reports and the general ledger are aggregated, they are computed from more granular events. When the data doesn’t make sense, you need the most granular data to debug what might have been the issue.

Saving data at the lowest granularity also makes it really easy to correct data that is derived from that dataset. If a single immutable dataset is the core source of truth for all views of that data, to correct the view all you need to do is rerun the pipeline that creates that view after fixing your data.

Similarly when accountants are preparing to close the books, they reconcile account balances with all the transactions that occurred to validate that the books are accurate. When a discrepancy is discovered, you can dig into the exact transaction that might be causing the issue.

Idempotency #

Every financial event can only be processed once, duplicates in the financial record will cause obvious inaccuracies. For that reason, all code that produces financial records should be idempotent.

Best Practices #

Over the years, I have run into quite a few gotchas that have caused me a lot of pain. Below are best practices I recommend, to avoid the many pitfalls I have personally faced.

Prefer integers to represent financial amounts. Makes arithmetic much easier. Certain decimal representations are okay, avoid floats at all cost.

Granularity of your financial amounts should support currency conversions with minimal loss of precision. If you are only working with dollars, representing values in cents might be sufficient. If you are a global business, prefer micros or a decimal like DECIMAL(19, 4). The decimal choice is quite popular among financial systems, but micros has been the standard for ads financial systems. This limits loss of precision when converting between currencies.

Wasteman’s note: Micros of a currency = base currency unit * 1,000,000. E.g $1.23 = 1,230,000 micros. I first came across this when working with Google’s metrics API.

Use consistent rounding methodologies. At scale the way you round can create material differences between expected amounts. For example one rounding methodology is to round all values 5 and up to the next significant digit, and 4 and below rounds down. Another valid way is to always round up. All that matters is you are consistent across the board. When you are dealing with millions of transactions, being off by 1 cent per transaction can lead to material differences. (10 million transactions off by 1 cent, leads to a difference of $100k). This may not be material to your business at this scale, but it’s material enough for the government to come after you for underpaying taxes.

Wasteman’s note: If you are a global business there can be a lot of gotchas with rounding and currency conversions. I would go as far as saying you should make a centralized library/service to handle both rounding and currency conversions. Different governments respect different rounding rules when calculating taxes, so having all these nuances abstracted into a single service will reduce complexity.

Delay currency conversion as long as you can. Preemptively converting currencies can cause loss of precision. Delay currency conversions until after aggregations occur in their local currency.

Use integer representations of time. This one is a little controversial but I stand by it. There are so many libraries in different technologies that parse timestamps into objects, and they all do them differently. Avoid this headache and just use integers. Unix timestamp, or even integer based UTC datetimes work perfectly fine. The less data conversions that occur between systems, the better. (Read about Etsy’s own problems with timestamp types here)

Wasteman’s note: I haven’t even talked about daylight savings related bugs. Using an incrementing integer can help you avoid this altogether. If you really insist on using datetimestamps, please at least use UTC. You would be surprised at how many very large businesses use non UTC timestamps.

Thanks for reading this post, I am sure I made a controversial statement somewhere but please feel free to comment and start a discussion. I am very open to learning and hearing other people’s thoughts. And if you enjoyed this post, consider supporting me by subscribing below!

And for further reading, here are some really good blog posts on accounting tailored towards software engineers.