Demystifying Quantum Theory Notes of Inverted Passion

Demystifying quantum theory - Notes of InvertedPassion #

Excerpt #

Demystifying quantum theory - Notes of InvertedPassion

Why is quantum theory so unintuitive? #

Quantum theory seems weird and hard to understand because we approach it from our world of classical objects. Our intuition is honed to see objects having different identities: an apple here or apple over there. Because we live in a 3D space, we can’t help but imagine any object (no matter how small or big) as having some shape in the same 3D space. And when we talk about “shape”, we inevitably create boundaries around objects and then because of boundaries, we can’t help but ascribe identities to objects. So, if there are two apples lying on the table, we really do see their boundaries and hence consider them as two different objects.

It also doesn’t help that our physics education starts with Newtonian mechanics where objects can be represented by neat little billiard balls. Then statistical mechanics takes it one step further and asks us to imagine atoms as infinitely small billiard balls (points) each with a specific position and momentum, bumping into each other. This visual isn’t much different than what we can imagine happening on an actual billiard table, so there’s no break in intuition from our familiar world to the world of Newtonian or statistical mechanics. Even Special and General Relativity maintain the same tradition. The only difference is that now little billiard balls are packets of energy/mass and bend the space-time around them.

However, when we come to quantum theory, all hell breaks loose. Suddenly, particles disappear and appear randomly. When we make measurements, we can’t predict outcomes. Sometimes particles are waves. Their location cannot be precisely determined. Their apparent communication between particles light years away. What’s happening?

Well, what’s happening is that we’re trying to apply our classical intuitions (particles as billiard balls, waves as propagation in a medium) to a context that doesn’t admit it. What if we try to understand quantum theory in its own terms and then see how classical intuitions emerge from it (rather than trying to start with classical intuitions)?

Understanding quantum theory on its own terms #

Five resources have helped me to build an intuition about quantum theory:

- Quantum Mechanics: the theoretical minimum

- My podcast interview with Chris Fields

- Quantum sequences by Elezier Yudolwasky

- Quantum mechanics is negative probabilities by Scott Aaraonson

- This comment on Hacker News

I highly recommend going through the resources above. But for an overview of the main ideas, keep reading.

If you haven’t noticed it so far, note that I’ve been talking about quantum theory and not quantum mechanics. I picked this from Chris Fields who said he prefers the term “quantum theory” because at the quantum level there’s no “mechanics” happening (at least in the sense of little billiard balls bouncing around). Of course, any type of dynamics can be called as mechanics so calling it “quantum mechanics” is not exactly wrong, but I’ve found that the word “mechanics” reinforces the notion of motion of 3D space and as you’ll see, 3D space in quantum theory isn’t fundamental.

In classical mechanics, the background setting (the “universe”) comprises of a 3D space containing particles (with each having a specific position and momentum). In this 3D space if some forces exist, they push around particles. But in quantum theory the 3D space is not fundamental at all. Rather, what’s fundamental is configuration space and instead of particles, what it contains is amplitudes. Let’s unpack this,

As the name suggests, configuration space is an abstract representation of possibilities. For example, imagine a particle with spin 0 decays into two particles. Now, according to conservation of angular momentum, we know that the two particles must have opposite spins (say, +1 and -1 or -1 or +1). We can represent these two options as anything, but let’s represent them as |+1-1> and |-1+1> (we could have represented these options as x and y or anything else, remember: it’s just a representation of possibilities).

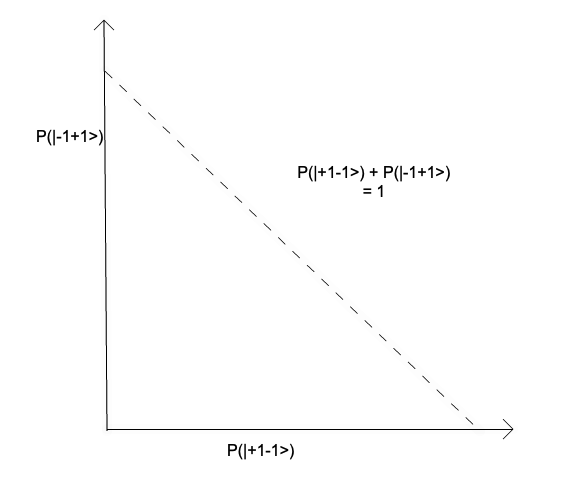

In the configuration space, we can represent these two possibilities as two dimensions and since the actual outcome can be either one of them, their probabilities have to add to 1.

Actually, these classic probabilities are not a fundamental thing in quantum theory. But let’s stick to them for a moment to see why the notion of 3D space is not fundamental. The configuration space above suggests that whenever we measure the spins of either of the particles, we can automatically guess the spin of the other particle no matter how far apart the particles are in 3D space. It’s like both you and your friends get one sock from each from a pair of socks. You don’t know which one you got but both of you travel away from each other with one sock. When you reach light years away from each other, you see which pair of sock you got. If you got the left pair, you know instantly that your friend must have gotten the right pair.

So, if configuration space is fundamental and that is determining what we observe, the notions of 3D space and identities take a back seat. The two socks are really one object because they’re bound together as a possibility in the configuration space. And their distance apart from each other in 3D space does not matter because they’re bound together as a possibility in the configuration space.

Actually, if this was what was actually happening in quantum theory, there would be no confusion. If we can demonstrate something with something as classical as a pair of socks, where’s the confusion? Probabilities as described above are not hard to understand.

Amplitudes are not probabilities #

Let’s examine the analogy of socks from a pair separating. The probabilities of two possibilities (that you got the left while your friend got the right one, or vice versa) exist only because you don’t have full knowledge of the system. If you could peek into the box containing the pair of socks and saw who picked which one, there would be no more probabilities. You would instantly know if you picked the left one or the right one.

This is the argument that Einstein and his colleagues gave where they argued that apparent probabilities observed in quantum experiments are due to our lack of knowledge about some “hidden variables” guiding the outcomes of experiments. Since we don’t have access to these hidden experiments, we get probabilistic outcomes. But those hidden variables exist somewhere out there and if we knew them, our experimental outcomes will be deterministic.

It turns out this assumption of “hidden variables” is not correct. The outcomes of measurements are truly probabilistic and no amount of knowledge can get rid of it. So, it’s not that we have a partial knowledge about state of our system in the configuration space and if we had full knowledge, we’d know what distinct state our system occupies (is it |+1-1> or |-1+1>). Instead, quantum theory says that that our system doesn’t have a distinct state until we measure it. It’s neither |+1-1> nor |-1+1>. Rather it’s a mix of both. The cat is both dead and alive.

How do we represent this superposition of possibilities?

Instead of using probabilities as dimensions of configuration space, we can use amplitudes.

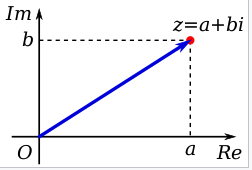

Amplitudes are complex numbers and the actual configuration space in quantum theory comprises not of probabilities as X and Y dimensions but of amplitudes. Since a complex number itself is represented by two dimensions, representing a two dimensional configuration space where each of the dimensions is itself a complex number is difficult. To see why, as a quick reminder, observe how a complex number requires two dimensions to represent.

For the sake of understanding what amplitudes are, let’s drop the imaginary part and simply assume that the dimension of the configuration space is a real number. This small change has a big implication because now we can admit negative numbers as values that different possibilities in a configuration space can occupy.

But what does it mean for a possibility to have a negative number? Isn’t probability always a positive number?

Yes, probability is always a positive number and that’s why amplitudes (that can be positive, negative or even imaginary) are NOT probabilities. Instead, the way we get probabilities is by squaring the number (or multiplying by its conjugate, in case of an imaginary number).

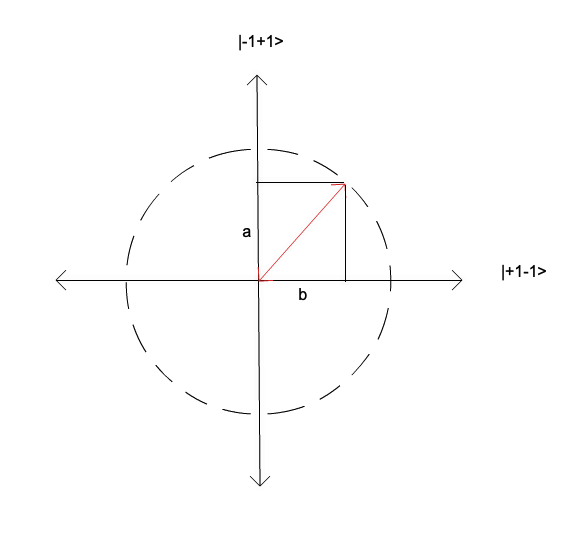

Assuming the same possibilities |+1-1> and |-1+1>, here’s how we will represent them in the configuration space.

Both a and b are real numbers here. Notice how which means the probability of either the possibility |+1-1> (which is ) or the possibility |-1+1> (which is ) adds to 1.

A configuration space of amplitudes where each dimension is a possible measurement is the correct way to visualize state of a quantum system. A couple of consequences of this is as follows:

- The state of a quantum system is represented as a vector in configuration space. Generally, this means we can represent quantum state as

- This combination of two possibilities into one state is what physicists mean by superposition

- The combined possibilities or is what physicists mean by entangled. The word entangled here means that measurements of the quantum system, vary together. If you know one part of the measurement, you instantly know all other parts.

- Both and are complex numbers and their squares give us probabilities of observing the corresponding measurements.

- The quantum system is the entire description of the system. Because it is in superposition of possibilities, does NOT have any intrinsic outcome until we measure it. Again, an important point: it’s not our lack of knowledge. The distinct possibility (as measured in our familiar 3d space) does not exist until we measure it. Before the measurement, though, the state of the quantum system is well-defined (as per the equation above) and evolves deterministically (if analogous to classic world, there are forces acting on the quantum system). It’s just that at the time of measurement, this deterministic evolution breaks down and we end up seeing one of the possibilities.

To sum up so far, quoting Chris Fields again, quantum theory is about systems where you can have full knowledge of the system without knowledge of its constituent parts.

Amplitudes are abstract #

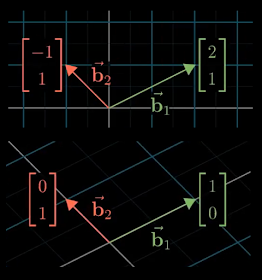

Here’s an important point regarding vectors. A vector can be represented as a combination of any other two vectors (that are not both pointing in the exact same direction).

For example, the same vector has co-ordinates (2,1) in X,Y basis where unit vectors as (0,1) and (0,1) but if you take different unit vectors as your basis, takes the co-ordinates (1,0). I hope it’s visible from the diagram above. If not, consider refreshing your linear algebra concepts.

What this suggests is that any vector can be decomposed into arbitrary number of basis vectors. So, can be seen as a sum of where a and b are two real numbers and and are vectors pointing in different directions.

How is this relevant to amplitudes?

Since amplitudes are vectors, they too can be seen as sum of any two unit vectors acting as basis vectors. As we saw above, the basis vectors are measurement outcomes which means for a quantum system, we’re not limited to measuring it in one particular way (say spin in only X direction, which is either |+1-1> or |-1+1>). We can measure the same quantum system in any way possible and it’ll spit out a measurement outcome. The probabilities of those new possibilities (say we’re measuring spin in the Z direction now) will be determined by decomposing the same quantum system in different basis vectors.

To solidify understanding, let’s go back to the example of measuring spin of a particle such as electron. Unlike the previous case, for simplicity’s sake, let’s assume there’s just one particle and no entanglement is going on.

Spin of a particle is a fundamental physical property that can occupy two values +1 or -1. We don’t have to worry about what it is right now. Let’s just assume that we have an instrument which we can orient in X,Y,Z direction and when we apply this instrument to the particle, it tells us spin of the particle in that direction.

If the instrument is aligned to the X direction, then if spin of the particle is aligned to the direction of the instrument, it says |up>. If spin is opposite to the instrument’s direction, it gives |down>

Now, let’s say a particle starts with some quantum state of the spin which we can represent as:

A property of quantum theory that we have not yet mentioned is that once you measure a system and obtain an outcome, the quantum system remains in the same state for all repeated measurements.

So, for example, if we use the instrument (aligned in the X direction) to measure the spin, we either get or .

Let’s rotate the instrument and orient in the Y plane so that it now reads the spin is or . What reading will you get if you measure the previous state of ?

We can’t derive this from math, but experiments tell us we have a 50-50 probability of getting either or . Since, we’re talking about the same system which was before and now it is either or , we can represent as a sum of and . That is:

The square root exists because to get probabilities of 0.5 for each possibility ( and ), we have to square the corresponding amplitudes (which is ).

Similarly, we can represent

Notice the minus sign which distinguishes from while keeping the possibilities of and as 50%-50% (because minus signs become positive on squaring).

The upshot of this transformation is that a quantum state is different from its measurement possibilities. Hence, the order of measurements matter in quantum theory. If you measure a quantum state in X direction first and then Y direction, you’ll get a different result from when you measure it in the Y direction first and then X direction.

This is called non-commutative behavior and this is why quantum theory is generally a theory in which operations are not commutative. To see this, imagine a quantum system that is in state . If you apply instrument aligned to X direction, you’ll get the measurement of . But now if you apply the instrument aligned to Y direction, you have 50% chance of getting or .

However, if you had measured with the instrument aligned to Y first, you still have 50% chance of getting or . But because measurements change the state of the quantum system, your system is now in either or and no matter which state is it in now, when you measure it with the instrument aligned to Y, now instead of always getting , you now have 50% chances of getting an and 50% chances of getting a . (Hope you can see why. Hint: just like we decomposed into a superposition of and , you can decompose or into a superposition of and ).

Bell’s inequality #

In their famous paper, Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen presented a thought experiment to argue that quantum mechanics may be incomplete. This was in response to prediction of quantum mechanics that in an entangled pair of particles, once we know measurement of one of the particles, we would instantly know the measurement of the other particle too (no matter how far apart they are). Einstein believed nothing could go faster than light (which is true) and that’s why he had a hard time accepting the instantaneous connection between the two particles in an entangled state.

They postulated that entanglement of particles can be explained via a set of “hidden” variables. These hidden variables determine outcomes of experiments, and if entangled particles share these hidden variables (say due to their common mechanism for creation/origin), then it shouldn’t be a surprise that our measurements give correlated results. This is sort of knowing that for a pair of socks, no matter which one you get, the other one will always be the opposite leg sock. EPR said that even though we may not know these hidden variables right now, in future we may discover them and then QM will become completely deterministic and the entanglement phenomena will no longer seem mysterious.

This argument sounded plausible until John Bell in his famous paper detailed how the presence of hidden variables is incompatible with predictions of quantum mechanics. Which means if QM is true, locality as proposed by Einstein did not exist.

Here’s how the experiment works.

Experimental setup #

Suppose you have a mechanism of producing entangled photos that always have the same polarization that’s either 0, 120 or 240 degrees. You also have Alice and Bob who’re measuring the polarization oriented to either 0, 120 or 240 degrees. Now, Alice and Bob pick orientation of their measurement apparatus randomly.

Question is: if this experiment is repeatedly thousands of time, how frequently should Alice and Bob expect both their apparatus to measure the polarization.

What John Bell showed that quantum mechanics made different predictions about the question above than what hidden variables would indicate.

Simulation #

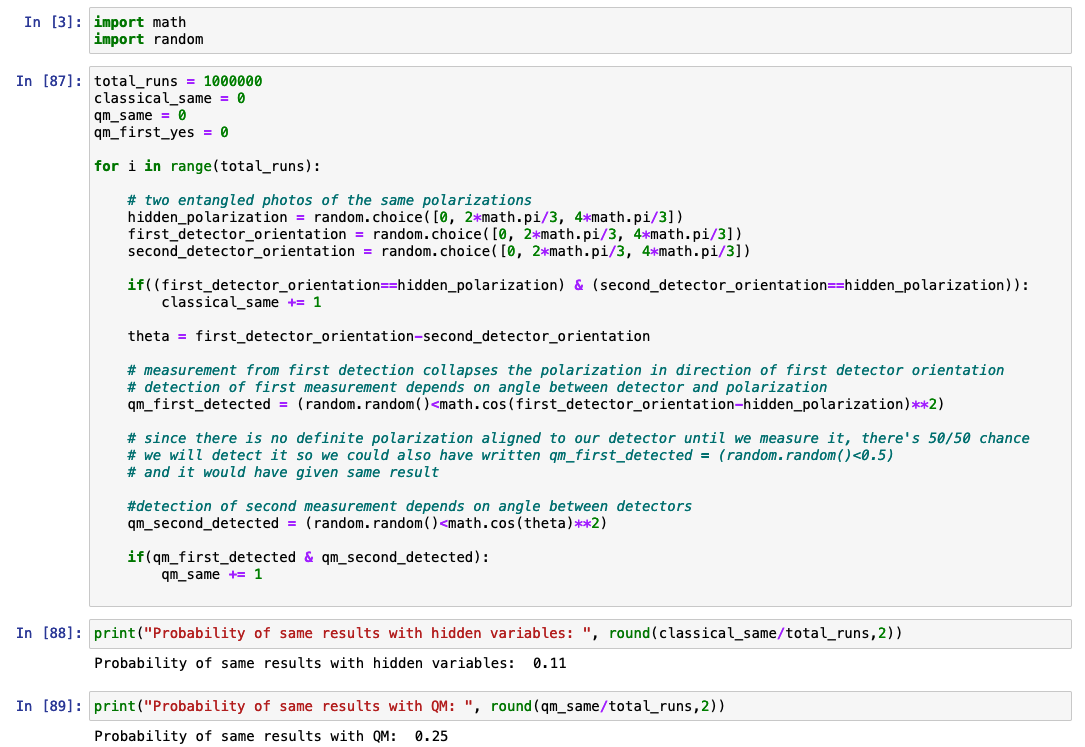

I ran a quick simulation to see what results would we get from QM and hidden variables in the scenario above. Here’s the snapshot of simulation:

So as you can see QM gives a different prediction of 0.25 probability than 0.11 probability of hidden variables of Alice and Bob getting the same result across all runs.

Real world experiment #

What Bell gave was a way to disambiguate which is right: QM or hidden variables. The only way to find which is correct is to do a real world experiment.

When real world experiment happened (and this has been replicated numerous times now), the experimental results agreed with QM predictions. Which means configuration spaces of quantum theory are indeed the deeper reality and since there’s no concept of our spacetime locality in configuration spaces, entanglement is really about one object which happens to manifest as two (entangled) particles far apart in our spacetime.