Demystifying General Relativity Notes of Inverted Passion

Demystifying general relativity - Notes of InvertedPassion #

Excerpt #

Demystifying general relativity - Notes of InvertedPassion

Demystifying general relativity #

The best summary of general relativity was given by John Wheeler when he said:

Matter tells spacetime how to curve, spacetime tells matter how to move

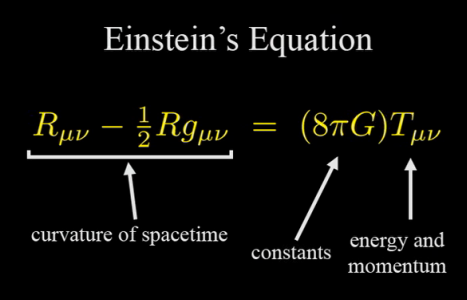

This can easily be seen in the Einstein’s field equations for general relativity:

As you can see in the equations, curved spacetime (described by the left part) = matter density (described by the right part)

In other words, curvature of the spacetime is literally just the amount of energy and mass contained in it.

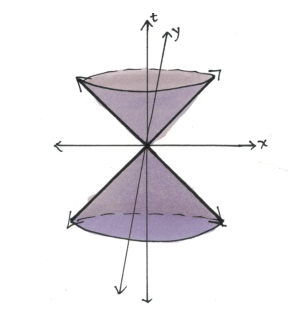

Tilted light cones #

In special relativity, light cones are useful visualizations. In the space time diagram, a light cone around any event indicates the future events that event can influence and the set of past events that could have influence this event. These light cones have a 45 degree angle boundary indicating light emitted from the event, since nothing can go faster than light all future events have to remain within the light cone.

The spacetime of special relativity (Minkowski space) is the one without any mass (and hence without any curvature, hence without any gravity). Hence, the Minkowski space is a special case of general relativity where curvature of spacetime is zero.

But, as we saw from Einstein’s field equations, if there’s matter (mass or energy), there will be curvature. The easiest way to see what curvature does is to see how light cones are impacted by nearby matter.

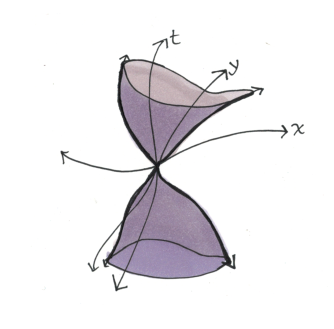

So, the curvature of the spacetime can be seen as light cones getting bent. The effect of light cones getting tilted and bent towards the matter can be seen in the new phenomena that general relativity predicts:

- Light bending around heavy objects (gravitational lensing) because the light cone around a massive object is bent (and light travels on the edges of this light cone)

- Time ticking slowly near a massive object as compared to lighter object. This is because the tilting of light cone converts the time velocity into spatial velocity, and hence proper time slows down near a massive object (this is the same effect as of the time dilation for a moving observer)

- Existence of black holes. Where light cones get tilted horizontally, meaning not even light is able to escape a horizon.

Let’s explore each of these in a bit more details.

Geodesics #

On a 2D plane, the shortest path between two points is a straight line. However, that’s not true for all surfaces. For example, on Earth (approximated as a sphere), the shortest path between two points is a circle on the surface of the sphere connecting the two points.

Geodesic is defined as the shortest path connecting the two points on a surface. Someone traveling on a geodesic path feels like they’re traveling straight (even if the surface has a curvature). As an aside, curvature is defined as positive if the sum of 3 angles of a triangle comes as >180 degrees, negative is it comes as <180 degrees and zero if it comes exactly as 180 degrees.

The key idea in relativity (both special and general) is that objects without any forces acting on them (in inertial frames) travel on geodesics paths that maximize proper time. In flat spacetime of special relativity, if no force is acting on an object, it will continue to travel straight in its world line (maximizing its proper time). In general relativity, the straight lines become geodesics because the spacetime is curved. What this emphasis on geodesic suggests that without any external forces acting on you, you’ll not feel anything as geodesics are a path of straight line. The following animation illustrates this point:

In other words, an object without any forces will travel a straight line in spacetime. It’s just that because matter curves spacetime, the straight lines bend towards the matter and that is what we observe as gravitation. The gravitation, effectively, does not exist. It’s simply a straight motion on a curved surface.

How time dilation happens #

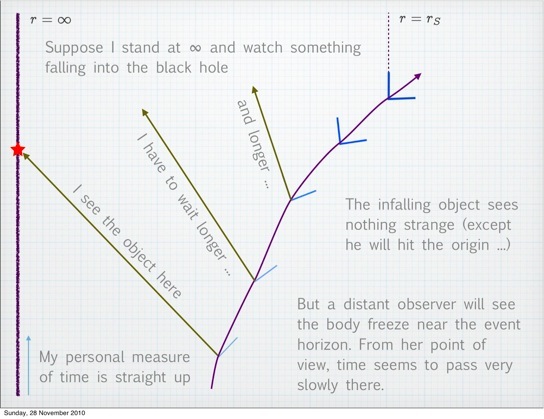

The easiest way to visualize phenomena in spacetime is to draw light cones. As we have seen, massive objects cause tilting of light cones towards themselves.

Imagine if light signals are sent to you from such successively more tilted light cones, such light cones will take longer and longer (in your reference frame) to reach you and you’ll perceive that as time slowing down near a massive object.

In relativity (both special and general), if we compare two world lines between the same events, the longer world line experiences lesser time as compared to the two. (This is why in twin paradox, as per Demystifying special relativity, twin with the longer world line ages more). This is a natural outcome of the fact that massive objects curve spacetime a lot more near them as compared to farther than them. So this curving increases the length of the worldline and hence time passes slowly near massive objects than far away from them.

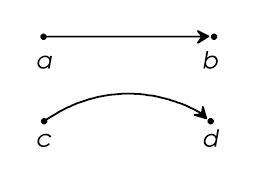

Here’s how to interpret the image above. Imagine the two points are in in my reference frame where I’m at infinity so that no gravitational impact is felt by me and I’m stationary. If there’s no massive object near the two points, they’ll have a path like AB but if there’s a massive object near them, they’ll have a path like CD. Since CD is longer than AB and speed of light is constant in all reference frames, looking from a distance it would seem like clocks ticking slower on CD than in AB (if I measure the straight line distance as one tick in my reference frame).

In other words, in strong gravitational fields, objects move slower in time since they have to travel a longer path.

Time dilation causes gravity #

For a while, I was stuck on the question of why gravity causes time dilation. But it is actually the other way around. For an object like a person in a gravitational field, the time ticks faster on her head than her feet. This differential velocity in time at two different spatial points near a massive object create a spatial velocity vector which we perceive as gravitational attraction.

Perhaps, a spacetime diagram can help illustrate this clearly:

Another good video on the same subject is this:

Space-space curvature #

Most of the gravitational effects that we observe near Earth is due to space-time curvature. But massive objects bend space-space slice of the entire 4D spacetime as well. We just don’t notice the effects of this curvature because we’re moving slow relative to the Earth but a fast moving object (like a light ray or a spaceship traveling close to the speed of light) will feel its space-space curvature as well.

What does the space-space curvature look like?

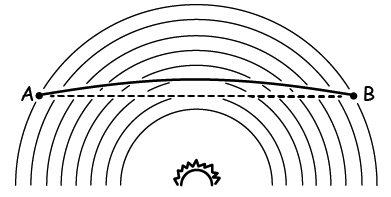

Notice that this is a 2D slice without any time dimension. However, because of bending of space around a massive object, the path between the two points that travels via the bend traverses a long path as compared to the path in flat plane (away from the massive object).

In popular depictions, the space around a massive object is depicted as follows:

This illustrates how the circumference of circles is longer near massive objects than you’d expect in a flat spacetime (because there’s a bulge due to massive object). However, this image a bit misleading because it assumes an extra dimension for bulge but in general relativity, we don’t need an extra dimension. The space-space paths are indeed longer due to massive objects.

What happens near a black hole: spacetime bending vs spacespace bending #

One way to understand general relativity is as follows. Assumes you have the flat spacetime where the speed of light is 1, which means one unit distance is 1 light second and one unit time is 1 second.

Now, put some matter (mass and energy) into it. What this matter does is that it makes both the units of distance and time longer near it as compared to far away in my reference frame where effects of that matter are nil.

The curvature in spacetime that I observe appears to me like space itself falling towards a point. (It appears like falling because if I observe you from a distance, it’ll appear like you automatically move towards the massive object even if you don’t do anything).

The curvature of space-space that I observe appears to me like light (or other objects) with the same velocity having to travel longer to arrive to me, closer they’re to a massive object than the time they would have taken if it were a lighter object.

The upshot of this is that it is useful to visualize general relativity as matter stretching the fabric of space (elongating the lengths in space) and making space fall towards itself with time (that too at an accelerating pace because time is curved more near the object than far from it). Only if spacetime falls faster as it is closer to the massive object will light take longer to reach a distant observer, hence making time appearing to tick slower closer to massive object.

Here’s a nice visualization of this spacetime falling (also called the river model).

A useful video explaining the same visualization is here:

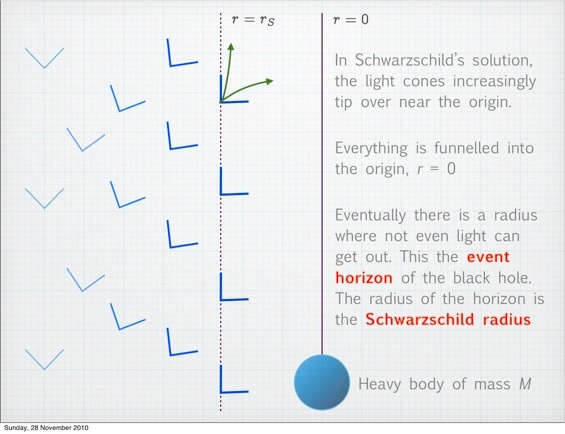

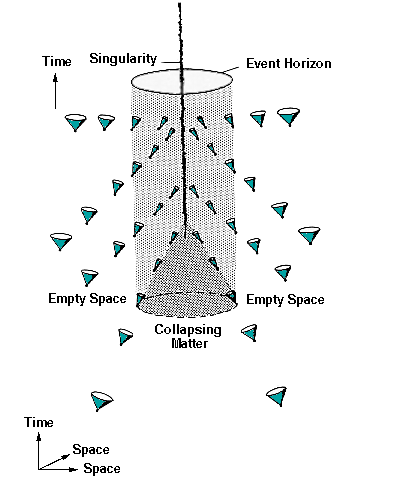

Another way to visualize this falling of space is to use light cones. Here’s how a light cone looks for a blackhole.

Notice two effects:

- Tilting of light cones. Inside the black hole, light cone completely tilts towards the spatial direction. This means even light cannot escape the spatial boundary marked by the event horizon. (In terms of falling space, this means inside the event horizon, the rate of falling of spacetime is faster than the speed of light so effectively even light cannot swim “upstream”).

- Shrinking of light cones. This is because viewed from your perspective of a far observer, light takes longer to travel between two points near a massive object because the path is longer due to space-space curvature.

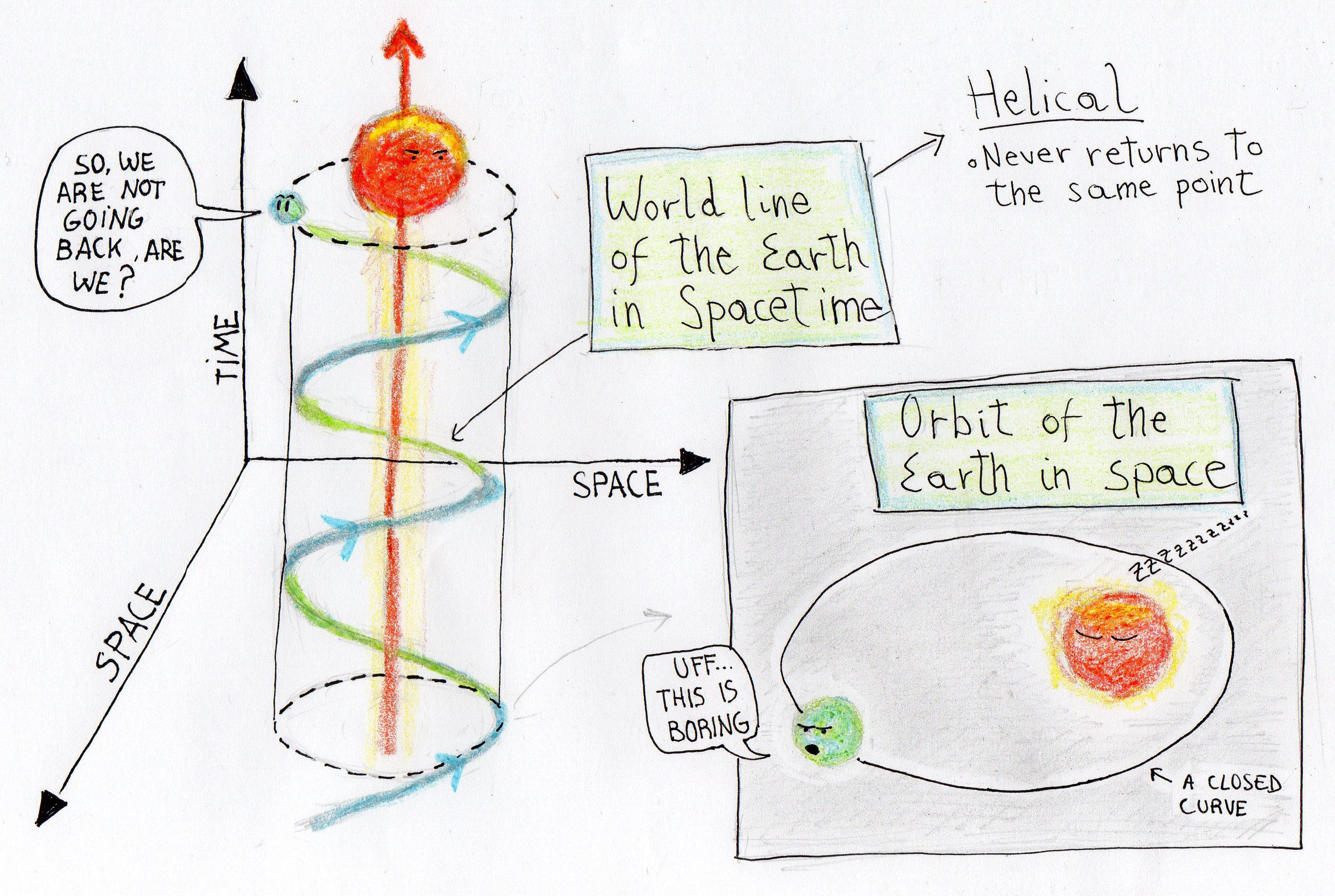

Why planets rotate #

They rotate because they have an initial velocity in a spatial direction that’s perpendicular to the time geodesic. So these two velocities add up to create a perpetual helical velocity in spacetime that appears to us as elliptical in space.

So, the Earth travels in a straight line (like all objects) but the geodesic (which is a straight line path) is itself curved near the massive object (Earth). In case of launched satellites, if the initial velocity is higher than the rate of spacetime curving, the satellite will move away but if it is lower than the rate of spacetime curving, it’ll simply fall towards the object. The initial velocity has to be just right so that the satellite always travels with an effective velocity equal to the tangent of the orbit.

Quantum considerations #

We know that the theory of general relativity is incomplete. This is because in the world of quantum mechanics, we’re not able to account for how spacetime is bent because of quantum fields / particles. Sure, some phenomena such as (black holes radiating energy as Hawking radiation) use both general relativity and quantum mechanics. But such analysis assume a specific spacetime curvature because of a massive object like a black hole and try predicting how quantum phenomena will behave around such curved space time. But nobody has been able to incorporate spacetime curving itself because of quantum phenomena. That is the holy grail of all efforts trying to come up with quantum gravity.

Also note that special relativity has been quite successfully incorporated into quantum theory, giving us quantum electro dynamics and quantum field theory. Here, particles or wavepackets moving near speed of light totally use length contraction and time dilation effects due to special relativity.

That said, as per Carlo Rovelli in the book Order of Time, we can imagine how spacetime will change if we successfully quantize it. He talks about following three effects:

- Discreteness: instead of values in spacetime continuously changing, we will have minimum units of plank time and plank length.

- Probabilistic light cones: instead of a definite light cone given by our formulas, we will get definite probabilities of what light cones should we expect if we measure it.

- Indeterminacy: until some measurement happens, the light cone will truly be indeterminate (like spin of a particle). This means we can probably expect phenomena like entanglement of (distant) light cones and so on.