An Event Driven Approach Is Not a Golden Hammer by Jarek Orzel Level Up Coding

An Event-driven Approach Is Not a Golden Hammer | by Jarek Orzel | Level Up Coding #

Excerpt #

Event-driven architecture (EDA) is a design paradigm in which system components communicate and operate through the production, detection, and consumption of events. In EDA, an event represents a…

[

]( https://medium.com/@orzel.jarek?source=post_page-----b1b9265ec7d6--------------------------------)[

]( https://levelup.gitconnected.com/?source=post_page-----b1b9265ec7d6--------------------------------)

Photo by Theo Crazzolara on Unsplash

Event-driven architecture (EDA) is a design paradigm in which system components communicate and operate through the production, detection, and consumption of events. In EDA, an event represents a significant change in state or occurrence within the system, and components (event producers) generate these events to signal state changes or actions. Other components (event consumers) respond to these events, triggering further processing or actions. This architecture promotes loose coupling, scalability, and flexibility, as components interact asynchronously and independently, reacting to events as they occur.

While asynchronous event-driven architecture (EDA) offers numerous advantages, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution. There are scenarios where using a REST API might be more appropriate or advantageous. Firstly, we need it when an immediate response is required. Moreover, the command approach when we call a given API endpoint can also be beneficial in asynchronous cases (and for example mimic async behavior using 202 Accepted response status).

I remember that a few years ago when I refactored a distributed system, I wanted to redesign the communication in that way to use events publish-subscribe pattern (pub-sub) everywhere. I had heard a lot that it promotes decoupling and autonomy of services. However, pub-sub is only a technical way of API implementation and should be secondary to logical relationships between bounded contexts.

In EDA event producer typically owns the contract between services. This ownership stems from the nature of events: they inform about significant state changes or occurrences within the producer’s domain.

Assume that we have a service that publishes a lot of various types of events and has a lot of consumers. In addition, it changes a lot over time because it is a core domain that we heavily iterate on. We often modify fields in the existing events and add new events. What’s the problem? Each event change must be updated on each consumer. It is not a huge worry (but it can cause issues) if my team owns the publisher and the consumers. On the other hand, there will be a great deal of effort, coordination, and communication load if separate teams maintain the two sides of the contract.

Please think about a table reservation use case. When a table is reserved we should notify the person who booked it. We consider two options:

TableReservedevent that is published byReservationServiceand consumed byNotificationService

Event-driven approach

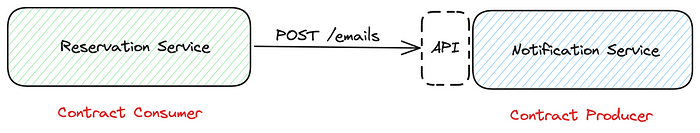

NotificationServiceREST API that provides an endpoint to send email/SMS/etc.

REST API command approach

At this stage, both options look straightforward. Please notice the important thing: in the events approach ReservationService is a contract producer, while in the REST API approach ReservationService is a contract consumer. It is a significant relationship difference that affects future development.

What happens when we get a new requirement from the business that canceling a reservation should also send a notification message to the customer? In the events approach we probably need to add a new event TableReservationCancelled to ReservationService and handle the event on NotificationService side. So, two services need to be changed. On the other side, the REST API approach only needs a change in ReservationService. Of course, it assumes that NotificationService API is quite generic and takes stable parameters like title, text, email_address, etc. Nevertheless, it is a crucial thing. The REST API approach could be advantageous if one side of the contract is stable and generic. Other examples of generic subdomains (I have written more about subdomains’ types

here) could be search engines or reporting. Due to its stability, the generic bounded context ought to be the relationship’s upstream side and provide a contract. If you want to get to know more about upstream/downstream relationships I strongly recommend the DDD Context map tool (e.g.

chapter 4 of What Is Domain-Driven Design? by Vladik Khononov).

To conclude, it is a really good idea before implementing a solution to ask the following questions:

- which component of the relationship is more stable and will not change a lot in the future?

- do we have a generic subdomain?

- do we have a circular dependency (both components impose a part of the contract)? Sometimes it happens when both components publish events that are consumed by each other. It is usually a design smell.

- does component

Ashould know anything about componentB? In our example, is it necessary forNotificationServiceto know anything about the concept of the table reservation?

Event-driven architecture is a really good pattern for designing microservices but sometimes we need to be flexible and mix it with other approaches.