Good Refactoring vs Bad Refactoring

Good Refactoring vs Bad Refactoring #

Excerpt #

Refactoring can make your code way better - or way worse. Here’s how to avoid messing up your codebase when you refactor code.

I’ve hired a lot of developers over the years. More than a few of them have come in with a strong belief that our code needed heavy refactoring. But here’s the thing: in almost every case, their newly refactored code was found by the other developers to be harder to understand and maintain. It also was generally slower and buggier too.

Now, don’t get me wrong. Refactoring isn’t inherently bad. It’s a crucial part of keeping a codebase healthy. The problem is that bad refactoring is, well, bad. And it’s surprisingly easy to fall into the trap of making things worse while trying to make them better.

So, let’s get into what makes a good refactor versus a bad one, and how to avoid being that developer everyone dreads seeing near the codebase

The good, the bad, and the ugly of refactoring #

Abstractions can be good. Abstractions can be bad. The key is knowing when and how to apply them. Let’s look at some common pitfalls and how to avoid them.

1. Changing the coding style substantially #

One of the most common mistakes I’ve seen is when developers completely change the coding style during a refactor. This often happens when someone comes from a different background or has strong opinions about a particular programming paradigm.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine we have a piece of code that needs some cleanup:

Before:

// 🫤 this code could be cleaner function processUsers(users: User[]) { const result = []; for (let i = 0; i < users.length; i++) { if (users[i].age >= 18) { const formattedUser = { name: users[i].name.toUpperCase(), age: users[i].age, isAdult: true }; result.push(formattedUser); } } return result; }

Bad refactor:

import * as R from 'ramda'; // 🚩 adopted a completely different style + library const processUsers = R.pipe( R.filter(R.propSatisfies(R.gte(R.__, 18), 'age')), R.map(R.applySpec({ name: R.pipe(R.prop('name'), R.toUpper), age: R.prop('age'), isAdult: R.always(true) })) );

While this refactored version might appeal to functional programming enthusiasts, it introduces a new library (Ramda) and a completely different coding style. For a team not familiar with this approach, it could be a nightmare to maintain.

Good refactor:

// ✅ cleaner and more conventional function processUsers(users: User[]): FormattedUser[] { return users .filter(user => user.age >= 18) .map(user => ({ name: user.name.toUpperCase(), age: user.age, isAdult: true })); }

This version improves the original code by using more idiomatic JavaScript methods like filter and map. It’s more concise and easier to read, but it doesn’t introduce a completely new paradigm or external dependencies.

2. Unnecessary abstractions #

I once hired someone who added tons of new abstractions without understanding the underlying code. They began grouping things that should not be grouped and were in the process of (intentionally) diverging over time. They consolidated some configurations that shouldn’t have been (different APIs needed different configurations).

Before:

// 🫤 this code could be cleaner function processUsers(users: User[]) { const result = []; for (let i = 0; i < users.length; i++) { if (users[i].age >= 18) { const formattedUser = { name: users[i].name.toUpperCase(), age: users[i].age, isAdult: true }; result.push(formattedUser); } } return result; }

Bad refactor:

// 🚩 there are way more layers and abstractions here than necessary class UserProcessor { private users: User[]; constructor(users: User[]) { this.users = users; } public process(): FormattedUser[] { return this.filterAdults().formatUsers(); } private filterAdults(): UserProcessor { this.users = this.users.filter(user => user.age >= 18); return this; } private formatUsers(): FormattedUser[] { return this.users.map(user => ({ name: this.formatName(user.name), age: user.age, isAdult: true })); } private formatName(name: string): string { return name.toUpperCase(); } } const processUsers = (users: User[]): FormattedUser[] => { return new UserProcessor(users).process(); };

This refactor introduces a class with multiple methods, which might seem more “object-oriented”, but it’s actually more complex and harder to understand at a glance.

Good refactor:

// ✅ cleaner and more conventional const isAdult = (user: User): boolean => user.age >= 18; const formatUser = (user: User): FormattedUser => ({ name: user.name.toUpperCase(), age: user.age, isAdult: true }); function processUsers(users: User[]): FormattedUser[] { return users.filter(isAdult).map(formatUser); }

This version breaks down the logic into small, reusable functions without introducing unnecessary complexity.

3. Adding Inconsistency #

I’ve seen cases where developers update one part of the codebase to work completely differently from the rest, in an attempt to make it “better”. This often leads to confusion and frustration for other developers who have to context-switch between different styles.

Let’s say we have a React application where we consistently use React Query for data fetching:

// Throughout the app import { useQuery } from 'react-query'; function UserProfile({ userId }) { const { data: user, isLoading } = useQuery(['user', userId], fetchUser); if (isLoading) return <div>Loading...</div>; return <div>{user.name}</div>; }

Now, imagine a developer decides to use Redux Toolkit for just one component:

// One-off component import { useEffect } from 'react'; import { useDispatch, useSelector } from 'react-redux'; import { fetchPosts } from './postsSlice'; function PostList() { const dispatch = useDispatch(); const { posts, status } = useSelector((state) => state.posts); useEffect(() => { dispatch(fetchPosts()); }, [dispatch]); if (status === 'loading') return <div>Loading...</div>; return <div>{posts.map(post => <div key={post.id}>{post.title}</div>)}</div>; }

This inconsistency is frustrating because it introduces a completely different state management pattern for just one component.

A better approach would be to stick with React Query:

// Consistent approach import { useQuery } from 'react-query'; function PostList() { const { data: posts, isLoading } = useQuery('posts', fetchPosts); if (isLoading) return <div>Loading...</div>; return <div>{posts.map(post => <div key={post.id}>{post.title}</div>)}</div>; }

This version maintains consistency, using React Query for data fetching across the entire application. It’s simpler and doesn’t require other developers to learn a new pattern for just one component.

Remember, consistency in your codebase is important. If you need to introduce a new pattern, consider how you can get buy-in from your team first, rather than creating one-off inconsistencies.

4. Not understanding the code before refactoring #

One of the biggest problems I’ve seen is refactoring code while learning it, in order to learn it. This is a terrible idea. I’ve seen comments that you should work with a given piece of code for 6-9 months. Otherwise, you are likely to create bugs, hurt performance, etc.

Before:

// 🫤 a bit too much hard coded stuff here function fetchUserData(userId: string) { const cachedData = localStorage.getItem(`user_${userId}`); if (cachedData) { return JSON.parse(cachedData); } return api.fetchUser(userId).then(userData => { localStorage.setItem(`user_${userId}`, JSON.stringify(userData)); return userData; }); }

Bad refactor:

// 🚩 where did the caching go? function fetchUserData(userId: string) { return api.fetchUser(userId); }

The refactorer might think they’re simplifying the code, but they’ve actually removed an important caching mechanism that was in place to reduce API calls and improve performance.

Good refactor:

// ✅ cleaner code preserving the existing behavior async function fetchUserData(userId: string) { const cachedData = await cacheManager.get(`user_${userId}`); if (cachedData) { return cachedData; } const userData = await api.fetchUser(userId); await cacheManager.set(`user_${userId}`, userData, { expiresIn: '1h' }); return userData; }

This refactor maintains the caching behavior while potentially improving it by using a more sophisticated cache manager with expiration.

5. Understand the business context #

I joined a company once with horrible legacy code baggage. I led a project to migrate an ecommerce company to a new, modern, faster, better tech… angular.js

It turns out, this business was heavily dependent on SEO, and we built a slow and bloated single page app.

We shipped nothing for 2 years besides a slower, buggier, and less maintainable carbon copy of the website. Why? The people leading this (me - I am the asshole of this scenario) hadn’t worked on this site before. I was young and dumb.

Let’s look at a modern example of this mistake:

Bad refactor:

// 🚩 a single page app for an SEO-focused site is a bad idea function App() { return ( <Router> <Switch> <Route path="/product/:id" component={ProductDetails} /> </Switch> </Router> ); }

This approach might seem modern and clean, but it’s entirely client-side rendered. For an e-commerce site that depends heavily on SEO, this could be disastrous.

Good refactor:

// ✅ server render an SEO-focused site export const getStaticProps: GetStaticProps = async () => { const products = await getProducts(); return { props: { products } }; }; export default function ProductList({ products }) { return ( <div> ... </div> ); }

This Next.js-based approach provides server-side rendering out of the box, which is crucial for SEO. It also offers a better user experience with faster initial page loads and improved performance for users with slower connections. Remix would be equally good for this purpose, offering similar benefits for server-side rendering and SEO optimization.

6. Overly consolidating code #

I once hired someone who, on their first day working on our backend, immediately started refactoring code. We had a bunch of Firebase functions, some with different settings than others - like timeout and memory allocation.

Here’s what our original setup looked like.

Before:

// 😕 we had this same code 40+ times in the codebase, we could perhaps consolidate export const quickFunction = functions .runWith({ timeoutSeconds: 60, memory: '256MB' }) .https.onRequest(...); export const longRunningFunction = functions .runWith({ timeoutSeconds: 540, memory: '1GB' }) .https.onRequest(...);

This person decided to wrap all these functions in one createApi function.

Bad refactor:

// 🚩 blindly consolidating settings that should not be const createApi = (handler: RequestHandler) => { return functions .runWith({ timeoutSeconds: 300, memory: '512MB' }) .https.onRequest((req, res) => handler(req, res)); }; export const quickFunction = createApi(handleQuickRequest); export const longRunningFunction = createApi(handleLongRunningRequest);

This refactor set all APIs to have the same settings, with no way to override per API. It’s a problem because sometimes we need different settings for different functions.

A better approach would’ve been to allow the Firebase options to pass through per API

Good refactor:

// ✅ setting good defaults, but letting anyone override const createApi = (handler: RequestHandler, options: ApiOptions = {}) => { return functions .runWith({ timeoutSeconds: 300, memory: '512MB', ...options }) .https.onRequest((req, res) => handler(req, res)); }; export const quickFunction = createApi(handleQuickRequest, { timeoutSeconds: 60, memory: '256MB' }); export const longRunningFunction = createApi(handleLongRunningRequest, { timeoutSeconds: 540, memory: '1GB' });

This way, we keep the benefits of the abstraction while preserving the flexibility we need. When consolidating or abstracting, always think about the use cases you’re serving. Don’t sacrifice flexibility for the sake of “cleaner” code. Make sure your abstractions allow for the full range of functionality that the original implementation provided.

And seriously, understand the code before you start “improving” it. We had issues the next time we deployed some APIs that could’ve been avoided without this blind refactoring.

How to refactor right #

It’s worth noting that you do need to refactor code. But do it right. Our code is not perfect, our code needs cleanup, but keep consistent with the codebase, be familiar with the code, be choosy about abstractions.

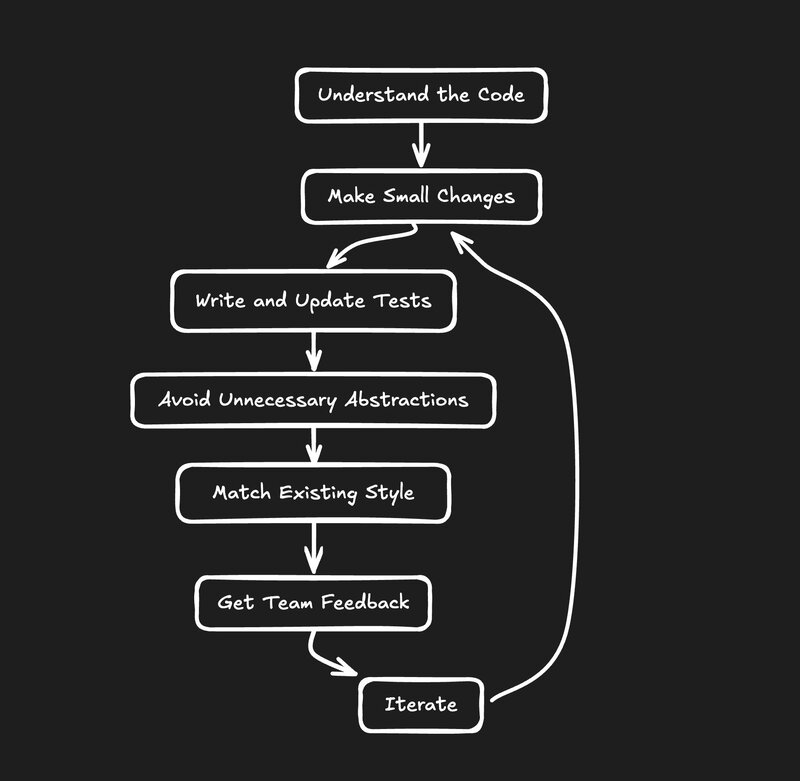

Here are some tips for successful refactoring:

- Be incremental: Make small, manageable changes rather than sweeping rewrites.

- Deeply understand code before doing significant refactors or new abstractions.

- Match the existing code style: Consistency is key for maintainability.

- Avoid too many new abstractions: Keep it simple unless complexity is truly warranted.

- Avoid adding new libraries, especially of a very different programming style, without buy-in from the team.

- Write tests before refactoring and update them as you go. This ensures you’re maintaining the original functionality.

- Hold your coworkers accountable to these principles.

Tools and techniques for better refactoring #

To help ensure your refactors are beneficial rather than harmful, consider the following techniques and tools:

Linting tools #

Use linting tools to enforce consistent code style and catch potential issues. Prettier can help auto-format to a consistent style, while Eslint can help with more nuanced consistency checks that you can easily customize with your own plugins.

Code reviews #

Implement thorough code reviews to get feedback from your peers before merging refactored code. This helps catch potential issues early and ensures the refactored code aligns with team standards and expectations.

Testing #

Write and run tests to ensure your refactored code doesn’t break existing functionality. Vitest is a particularly fast, solid, and easy-to-use test runner that requires zero configuration by default. For visual testing, consider using Storybook. React Testing Library is a great set of utilities for testing React components (there are Angular and more variants as well).

(The right) AI tools #

Let AI help you with your refactoring efforts, at least those that are able to match your existing coding style and conventions.

One tool that’s particularly useful for maintaining consistency while coding frontends is Visual Copilot. This AI-powered tool can help you turn designs into code while matching your existing coding style and correctly leveraging your design system components and tokens.

Conclusion #

Refactoring is a necessary part of software development, but it needs to be done thoughtfully and with respect for the existing codebase and team dynamics. The goal of refactoring is to improve the internal structure of the code without changing its external behavior.

Remember, the best refactors are often invisible to the end-user but make life significantly easier for developers. They improve readability, maintainability, and efficiency without disrupting the overall system.

The next time you feel the urge to make “big plans” for a piece of code, take a step back. Understand it thoroughly, consider the impact of your changes, and make incremental improvements that your team will thank you for.

Your future self (and your colleagues) will appreciate the thoughtful approach to keeping the codebase clean and maintainable.

Oh also do you like YouTube vids? Theres a video on this too from yours truly:

About me #

Introducing Visual Copilot: convert Figma designs to high quality code in a single click.