10 Things Software Developers Should Learn About Learning

10 things software developers should learn about learning #

Excerpt #

A scientific understanding of how human memory, learning, and problem solving work.

This is the latest issue of my newsletter. Each week I share research and perspectives on developer productivity.

By the way, we’re hosting a discussion with Manuel Pais, co-author of Team Topologies_, later this month on structuring your platform engineering team. Sign up to join us here._

This week I read 10 Things Software Developers Should Learn about Learning, a paper that distills research findings about how memory and learning work. I found this paper particularly insightful not only for developers eager to master their craft but also for leaders engaged in recruiting and training.

My summary of the paper #

As software developers, continuous learning isn’t just beneficial—it’s a distinguishing attribute of great engineers. Yet, just because we learn doesn’t mean we understand how we learn.

This paper distills findings from prior work on learning that apply specifically to software developers. I’ve summarized the ten lessons here, and have organized them into themes.

How human memory and learning work #

1. The unique nature of human memory

Unlike computer memory, which operates through straightforward ‘read’ and ‘write’ functions, human memory is more complex. When we attempt to recall information, we activate a network of neurons, leading to a phenomenon known as ‘spreading activation.’ This process isn’t limited to specific pathways and can facilitate unexpected connections and insights. It’s often why stepping away from a complex problem and engaging in unrelated activities—like taking a walk or a shower—can lead to innovative solutions through these unexpected neural connections.

2. Human memory includes two systems: long-term memory and working memory

Human memory consists of two main systems crucial for learning: long-term memory, where information is stored permanently, and working memory, which is used for processing and solving problems. Having higher working memory may help developers ramp-up faster, however it’s the contents of their long-term memory that distinguishes experts.

Techniques like ‘chunking,’ where related information is grouped into larger, manageable units, enhance our ability to retain and process data in working memory, facilitating deeper expertise over time.

When adopting new tools or skills, it’s also important to gauge the cognitive load involved. This load can stem either from the inherent complexity of the task (intrinsic load) or the way the information is presented (extrinsic load). Cognitive load can be reduced by either breaking down complex problems into simpler parts, or by improving the presentation or delivery of information.

How to become an expert #

3. Experts recognize, beginners reason

If you have read Thinking Fast and Slow, you’re familiar with the idea that our cognition operates through two systems: one that is fast and driven by recognition, and another that is slower and more focused on reasoning. Research has identified that because expert developers can recognize common patterns in code (they’ve seen the problem before, or something like it), they can process and address problems more quickly with less effort. Beginners, on the other hand, might have to read line by line to try and understand the workings of the code. Beginners can therefore become experts faster by reading and understanding a lot of code.

4. Learn new concepts by starting going from abstract → concrete → abstract

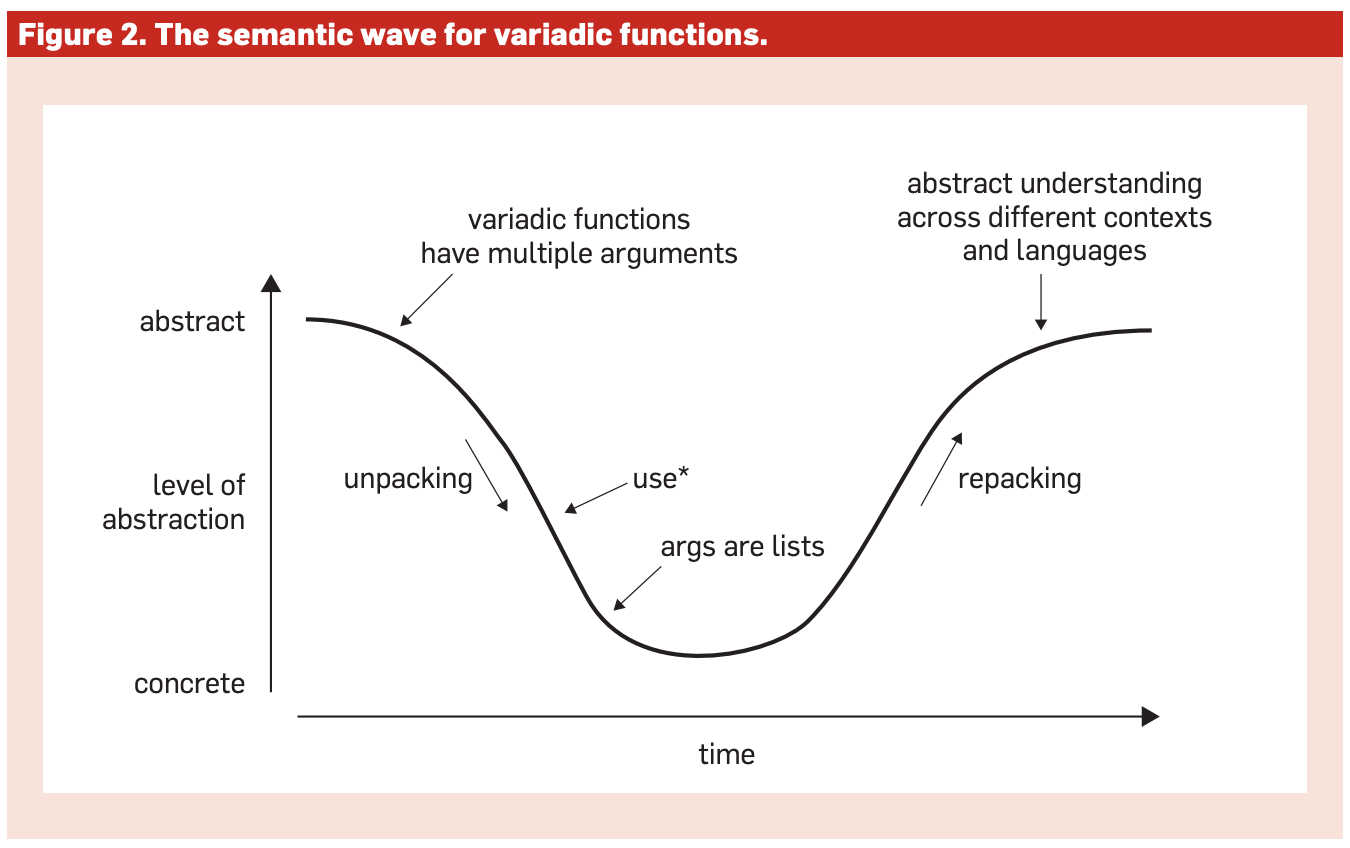

When we’re learning something new, we benefit from both abstract and concrete forms of explanation. More specifically, the most effective way of learning something new is to start with an abstract definition of a concept, then go to concrete examples (including wrong examples), and then back to revisit the abstract idea. (Beginners often start and stay with concrete examples of an idea.) Switching between the two helps us understand complex ideas more fully. This is called the semantic wave, as illustrated in the image below.

[

5. Memorization is still important, even with the internet and AI

Despite the accessibility of information via the internet and tools like ChatGPT, memorization is still an important skill. It facilitates quicker pattern recognition and supports higher levels of abstraction and understanding, effectively reducing cognitive load and increasing problem-solving speed.

Additional strategies to improve learning #

6. Use spacing and repetition to your advantage

There’s a concept in cognitive psychology called the spacing effect: it’s the idea that the best way to learn problem-solving concepts is to use both spacing and repetition. That’s as opposed to cramming information in as little time as possible. Spacing refers to doing regular practice sessions, spaced out over multiple days or weeks, and repetition is revisiting topics again and again.

7. Problem-solving is not a generic skill. To get better at programming, practice programming

‘Problem-solving is not a general skill that can be learned. Rather, we learn how to solve problems within specific domains, such as with programming, chess, or knitting. Each of these problem-solving skills is separate and does not influence the others. For example, research into chess found little or no effect of learning it on other academic and cognitive skills, and the same is true for music instruction and cognitive training. In other words, the best way to learn how to solve programming problems is to practice solving programming problems, rather than looking for performance benefits from learning other skills or any other kind of cognitive training.

Interestingly, this also applies to hiring. Google used to be famous for asking candidates to solve brain teasers, but they later found that this was a waste of time. There is no reliable correspondence between problem-solving in the world of brain teasers and problem-solving in the world of programming.

Insights for recruiting and training #

8. Experts aren’t always the best trainers

Experts can sometimes fail at training beginners because they fail to tailor their explanations for someone with a different mental model. This is known as the expert blind-spot problem: difficulty in seeing things through the eyes of a beginner once you have become an expert. This is why beginners may benefit more by learning from a more knowledgeable (but still relatively novice) peer.

Additionally, knowledge transfer between programming languages can lead to faulty knowledge. The authors give this example: “a programmer may learn about inheritance in Java, where one method overrides a parent method as long as the signatures match, and transfer this knowledge to C++, where overriding a parent method additionally requires that the parent method is declared virtual.” These kinds of differences—where features are similar in syntax but different in semantics between languages—hinder the transfer of knowledge.

9. It is very hard to predict who will be able to program

Someone’s ability to learn programming likely depends on a mix of aptitude and practice. However, research has failed to identify links between either and someone’s ability.

For example, research has found that all of the following fail to predict programming ability: gender, age, academic major, race, prior performance in math, prior experience with another programming language, and preference for humanities or sciences. There’s mixed evidence for the importance of years of experience (which relates to practice). And while there are weak causal links between general intelligence and working memory capacity, and someone’s success in early programming, even these two factors are more predictive of someone’s rate of learning rather than their absolute ability.

10. Having a growth mindset matters

When learners tackle new challenges with a growth mindset, they not only persist through obstacles but also navigate failures more effectively. Cultivating a growth mindset, however, is itself a skill, not merely an attitude adjustment.

Closely linked to this is the concept of goal orientation, which bifurcates into two distinct types: approach and avoidance. An approach orientation focuses on achieving success and fosters productive learning behaviors, while an avoidance orientation is more about dodging failure. It’s important to create environments where making mistakes is part of learning, not a source of penalty. This helps team members towards approach rather than avoidance.

Final thoughts #

This paper is packed with insights that can help refine our approaches to hiring, training, and learning. One standout observation in the realm of hiring and training is the surprising lack of reliable proxies for programming proficiency. Common requirements like years of experience or familiarity with multiple programming languages fall short in accurately assessing a candidate’s capabilities. Instead, the only reliable method to gauge programming skill is through evaluating previous work or conducting tests on practical programming tasks.

The insights about how we learn were interesting too, and mostly reinforce what many of us might already expect. For instance, the benefit of taking breaks from a problem to enable a solution to emerge, or the advantage of spaced learning sessions over cramming, are both affirmed by research.

Thank you for reading Engineering Enablement. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Who’s hiring right now #

Here’s a roundup of new Developer Experience job openings:

Foursquare is hiring a Product Manager for Platform Engineering | New York

Plaid is hiring a Product Manager - Developer Platform | San Francisco

Rocket Money is hiring a Team Leader - Engineering Performance & Developer Experience | Various cities or remote (US)

SEB Bank is hiring a Head of DSI Developer Experience | Stockholm

Sprout Social is hiring an Engineering Manager - Developer Experience | Remote (US)

Uber is hiring a Senior Staff Engineer - Developer Platform (Gen AI) | San Francisco and Seattle

Find more DevEx job postings here.

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading.

-Abi

Subscribe to Engineering Enablement #

The latest research and perspectives on developer productivity.