A Video Game That Pays Lessons Learned From Working Remotely

A Video Game that Pays: Lessons Learned from Working Remotely #

Excerpt #

Engineering, Robotics, AI, Technology

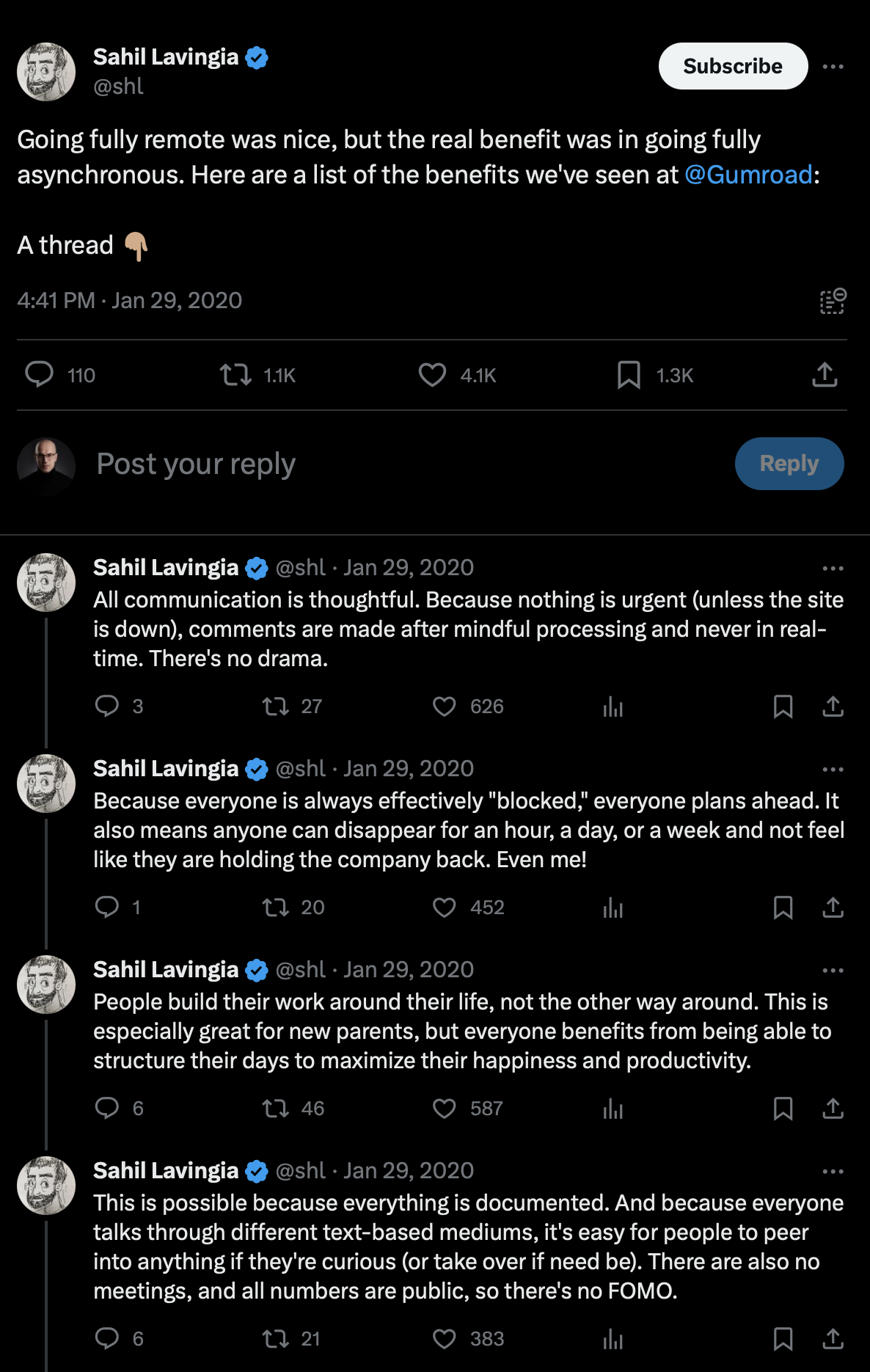

The original tweet by Sahil Lavingia

Some time ago, I stumbled upon this amusing tweet from @shl. I love how true this statement is, although it feels very wrong to admit it. Let’s think about the day in the life of a software engineer:

- You interact with people from all corners of the world.

- You complete tasks on different online platforms (Slack, GitHub, VS Code, Google Docs, etc.).

- You have a list of your main quests to complete (you can find them in your journ… Kanban board!)

- There are also side-quests to take care of (“Hey Damian, could you take a look at this bug?”).

- Sometimes you can gang up with your teammates to slay a big beast (“Hey, I have this nasty bug that I have been working on for the past few days. I know you have better knowledge of this particular part of the repository, could we jump on a pair programming session?”).

- And you get to level up once in a while!

Playing a game that pays you money is cool for one important reason. Nobody can give you a hard time playing - after all, the game pays money.

I enjoy exploring the similarities between video games and remote software engineering. However, on a serious note, remote work has its own set of pros and cons, which those experienced in this field are well aware of. Having worked remotely for almost two years, I’ve gained some valuable insights and lessons that I want to share in this blog post. I believe these insights could be helpful to others, especially as more people are considering remote work after the Covid era.

Trust - The Currency of Success in Remote Work #

It is said (source: “So Good They Can’t Ignore You” by Cal Newport) that there are three traits that characterize work done with passion: creativity, impact, and control.

This last trait, control, especially control over our schedule, is what makes remote work so liberating. As long as you deliver quality work, you are (to a large degree) free to plan your day according to your preferences. You have the flexibility to blend your work schedule with your personal life. You are trusted to find your best individual way to contribute to the company. I find this very motivating.

However, working remotely often demands much more discipline and self-organization than an onsite position. In the office, it is often easy to confuse physical presence with productivity. I am fairly convinced that merely showing up to work and producing limited output is enough for people to “survive” for years in some organizations. Even though they do not produce meaningful output, this is not important, as long as they “show up”. Remote work, on the contrary, is more about building trust through continuously producing quality output, in the absence of the physical presence.

Do you remember the infamous Elon Musk ‘laptop class la-la land’ interview? While I disagree with his claim that remote work is immoral, I understand his concern about productivity. At the same time, I also have strong reasons to believe that in many cases, Elon would have no problem hiring a remote software engineer if he could trust them enough.

If you are working in a remote setting, you should ensure that your colleagues trust you and can rely on you. Even if you are not online at the moment, they should know that you eventually will be there and not leave them hanging. The goal of building trust is to eliminate potential friction that arises due to the lack of physical presence.

There are a few simple rules that I try to enforce every day to make my remote colleagues’ lives easier:

- Always try to end your day in a way that allows the people you interact with to seamlessly pick up where you left off.

- Communicate and work asynchronously. If you want to work fully remotely, it is extremely important to learn how to work asynchronously.

- Do not leave people hanging. If someone asks for your help, either help them or communicate that you cannot do so.

Being a trustworthy remote colleague means that your team and managers can rely on you. They understand that your good work helps them do good work, even if they do not physically see you doing it.

@shl makes some great points here. He often shares lessons learned from running his company, Gumroad, which is 100% remote and async

Clarity and Precision: Slow is Smooth and Smooth is Fast #

Imagine you’re sitting at your office desk, fiddling with the idea of getting a cup of coffee. Despite this, you manage to quickly send a message to your friend, notifying her that you encountered a bug after her changes. Then you go grab a coffee. If she did not understand your message, you can quickly visit her desk on the way back from the kitchen and explain in more depth what your perhaps somewhat hasty and imprecise message was all about.

However, when you work remotely, you never know if your colleague is online. Even worse, by the time she comes back and reads your message, you may no longer be online. This brings me to my main point:

You want to leave your messages in a state where your colleagues can quickly act on them without needing additional clarification. This ties back to the previous point about asynchronous communication. Your messages should leave no room for ambiguity and enable your colleagues to promptly understand what they need to work on.

Let me provide a few examples:

You are blocked by an error introduced by your colleague’s pull request. You currently can’t fix it, so you want to give her a heads-up that her diff broke the functionality. What should you do?

Bad: Leave an imprecise, sloppy message like, *“Hey, X, have you seen this before: [insert the last line from the stack trace]? Please help!”

Good: Leave a detailed description of the problem, including the full stack trace (not just the last few lines), along with an explanation of what you were trying to achieve, what your environment is, and how to reproduce the problem.

or

You have a proposal for a feature or a design solution that you want to share with the team.

Bad: Leave a convoluted, unstructured, hasty explanation that, ironically, raises more questions.

Good: Provide a short, high-level description of what you would like to implement and include a piece of pseudocode, a flowchart, or a diagram. It doesn’t matter whether you use a formal language like UML or any other visual representation. The key is to efficiently compress your ideas into a format that will enable your colleagues to accurately reconstruct your mental model.

Yes, following this advice may take an extra 10 minutes of your time, but it will save you twice that time by avoiding back-and-forth exchanges with your team. It will also provide nicely documented material for future reference and show that you are a good communicator who is mindful of the time of your teammates. Remember: slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.

Embrace the Small Time Zone Overlap #

Very often, in a remote setting, there is a time zone difference between you and your colleagues. If you are working remotely from Brazil and interacting with the European team, your colleagues are most likely finished before your afternoon. Whether you like it or not, they most likely will not be available for a good part of your evening. For some, this may be frustrating. What happens if I get stuck working on a task? Do I need to wait until the next day for my colleagues to step in?

From my experience, most people in their work environment struggle with the opposite problem - the lack of time to work on their own. We often have difficulty “blocking off” the “focus time”. We are in a perpetual context-switching loop. In our calendars, we try to schedule time blocks in advance, hoping to muster up half an hour of concentration time. Very often, we go to some isolated part of the office so that we can work alone on the problem at hand. Serendipity at the workplace is cool, but many companies embrace it so much that employees cannot focus on meaningful deep work. I remember suffering from the same problem when working in the office. I was trying all sorts of creative ways to shield myself from distractions. All the attempts at downloading calendar-blocking apps or openly communicating my focus-time hours were quite futile. The final solution was also suboptimal - showing up in the office at 7 a.m. to get some tasks done before most of the employees arrived at 9 a.m.

Most remote workers are blessed with a few hours when they are not being pinged and have no need to check their email/Teams/Slack/etc. They have the comfort of knowing that every day there are at least a few hours free from the beehive buzz. So their schedule is naturally divided between “deep work” done in seclusion and then back-to-back meetings, discussions, and other attention-grabbing interactions. I find the natural division of the daily schedule productive. It allows for enforcing more structure and thus maintaining better control of your time.

A 40-hour time-blocked work week, I estimate, produces the same amount of output as a 60+ hour work week pursued without structure. - Cal Newport

Meetings: Less is More #

One could naturally flip my argument and say that working across time zones (and thus a limited overlap window) may be harmful to the productivity of an organization. There is only a limited time window in which all team members or the larger part of the organization is available for synchronous meetings. I can recognize how this may be a disadvantage: if there are so few opportunities for all people to meet at the same time, how does the information flow through the company, and how can any sensible decisions be made?

But then again, have you ever worked in an organization that has suffered from too few meetings? It is mostly too many meetings! Any company, especially one that grows fast, is very fertile soil for unnecessary meetings to grow like weeds. Recently, @johnlqian wrote a short and nice blog post about how startups lose the spark as they scale. He points out that the proliferation of unnecessary meetings is one of the main factors.

During my time at Tesla, despite the company’s size, I think we did an okay job of protecting our schedules. This was the result of the rules established by Elon: “Excessive meetings are the blight of big companies and almost always get worse over time”. Tobias Lütke, the CEO of Shopify, is also very critical of excessive meetings. Critical to the point where Shopify conducts periodic “calendar purges” to avoid trudging through the swamp of meetings.

Excessive meetings are like an anchor that serves its purpose until it no longer does, resulting in slowing down the whole organization. So if you are a remote-first company, embrace the blessing and the curse of a limited time overlap. You most likely will not be able to spin out multiple series of all-hands, dailies, stand-ups, syncs, or war council meetings. Your meeting budget is fixed and modest, so you need to be mindful of how to spend it. This restriction should be positive in the long run. It should coerce organizations to build a sensible and efficient approach toward the quality and quantity of meetings.

Conclusion #

For me, going remote was very rewarding. My commute has decreased by 2 hours daily. I have returned to running marathons, take much better care of myself, and spend much more time with my loved ones. I am also much more productive, and able to disentangle deep work in isolation from times when I need to be available for collaboration and context-switching.

Let’s also be clear, remote work is not all unicorns and rainbows. The lack of physical contact with other human beings is, personally, my biggest issue. You can no longer take the act of randomly bumping into one another and spontaneous discussions for granted, as you would in the office. I realized how much I miss meeting with my colleagues at 8 a.m. for an objectively mediocre yet delicious office coffee that gains its value from the social context. In the remote setting, socializing among colleagues needs to be actively managed. While some may think that working remotely may be perfect for introverts, it may be worthwhile to be the force that brings the group together. Putting more direct effort into building relationships, setting up pair-programming sessions, or initiating watercooler talk may benefit everyone.

After the first onsite with Neural Magic, where I got to finally meet the people in the flesh, my team’s productivity significantly boosted. Getting to know people and realizing that they are interesting, passionate individuals rather than pixels on a screen improved our communication and collaboration immensely.

I hope that this write-up was useful for you. Remote work is like playing a video game that not only makes money but also hopefully allows you to grow and have a positive impact on the world.