Multi Coring and Non Blocking Instead of Multi Threading

“Multi-Coring" and “Non-Blocking“ instead of “Multi-Threading” - with a Script - Page 3 of 4 - IT Hare on Soft.ware #

Excerpt #

Abstract:My talk at ACCU2018[→]

Now, as we’re done with describing an individual (Re)Actor, we can proceed to discuss “how to build THE WHOLE SYSTEM consisting of nothing but (Re)Actors” (well, “almost nothing”, as usually – though not necessarily – Infrastructure Code happens to be NOT (Re)Actor-based).

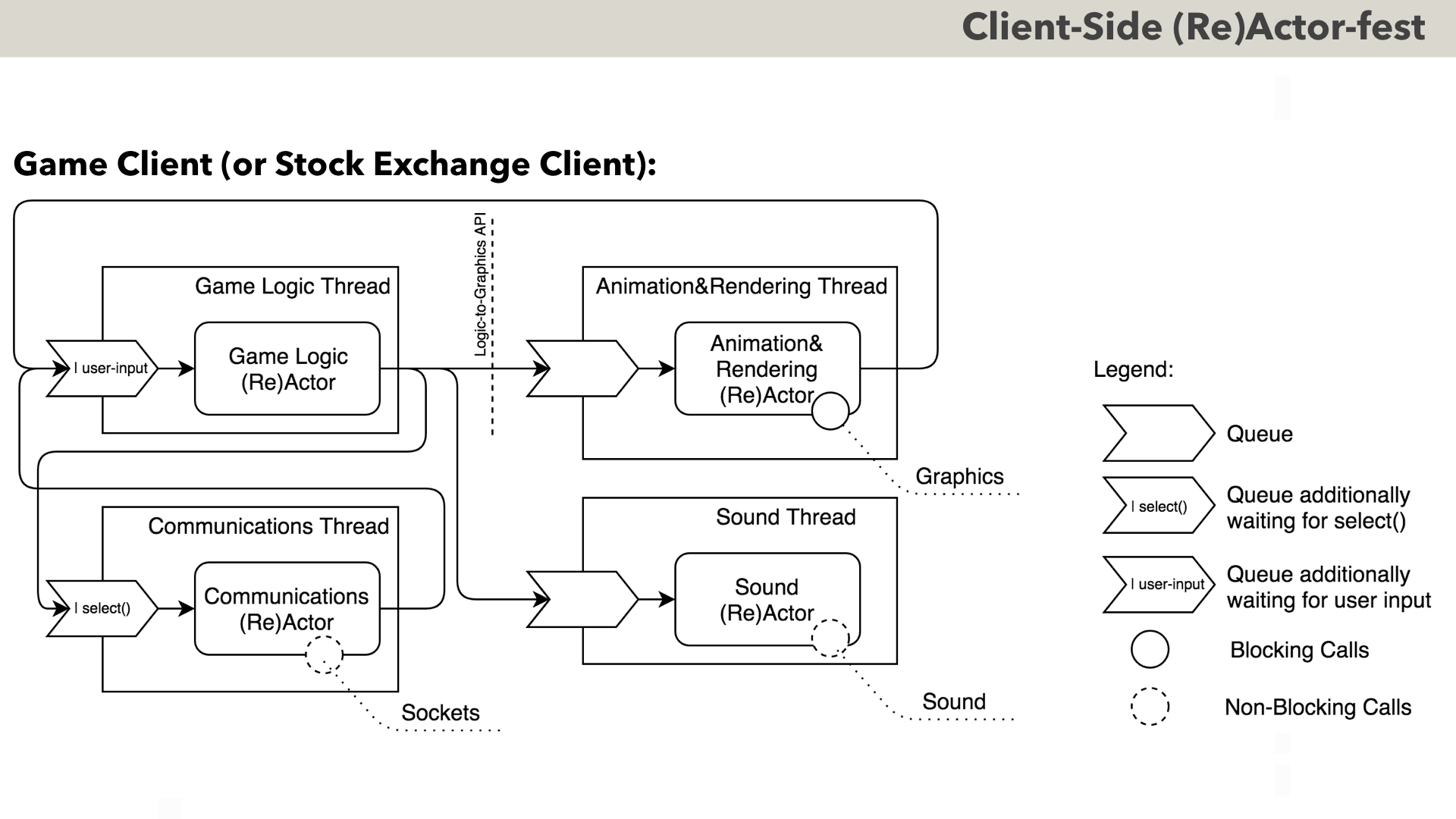

First, let’s discuss (Re)Actor-fest architectures on the Client-Side. Here, I have to note that MOST of the Client-Side Apps are event-driven to start with; in fact, I don’t know of one single GUI framework which is NOT event-driven.

For a usual business app one single core (and therefore, single-threaded (Re)Actor) is usually more than enough; however, let’s consider something more complicated – a Game Client (or a Stock Exchange Client, which, believe it or not, is not THAT different).

As we can see, everything is quite simple here: we have a bunch or (Re)Actors, which communicate with each other via queues; in addition, some of these queues receive information from the outside world (user input, and network via select()). Inside, most of the (Re)Actors MAY call system-level functions to perform certain operations. If the call is guaranteed to complete “fast enough” (such as most of graphics calls) – then we can rely on that “(Mostly-)” prefix in Mostly-non-blocking, and call it in a blocking manner.

However, if the call is of indeterminate length (such as ALL Internet-related calls in Communications (Re)Actor) – we will issue a NON-blocking call and will wait for the result asynchronously. For Communications (Re)Actor, within our Infrastructure Code we’ll usually wait for select()-like function (in practice – it can be poll(), epoll(), WaitForMultipleObjects(), etc). When select()-like function returns – our Infrastructure Code will EITHER convert network packet into an event, OR will ensure that it is received by app-level code after respective await operator returns (in C++, it is done by implementing await_resume() function of an awaiter object).

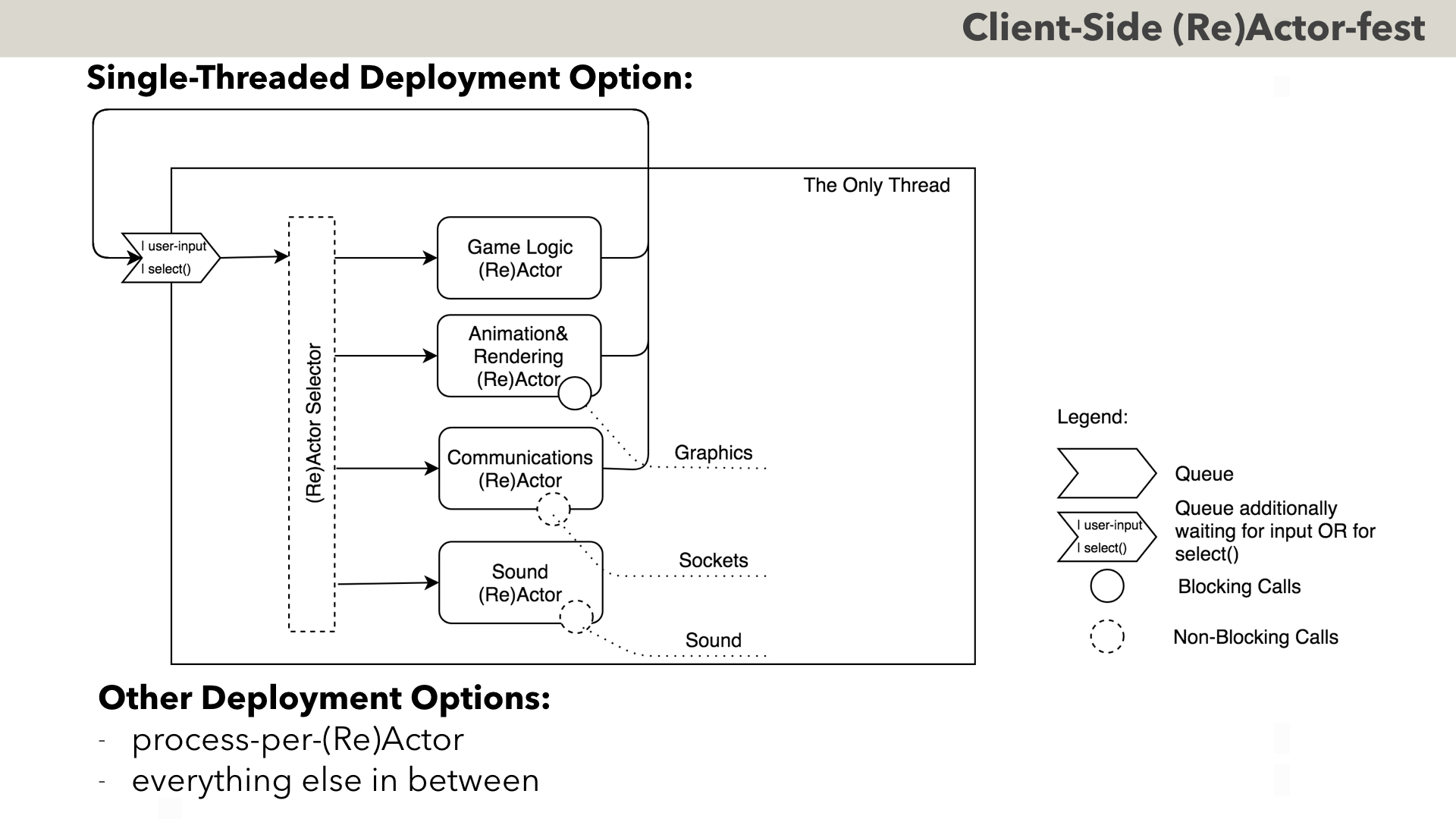

As always with (Re)Actors, all kinds of different deployment options are possible. If our game is a social game or a stock exchange – the following single-threaded configuration is possible. It is about the same thing – but with EXACTLY THE SAME (Re)Actors moved to the main thread of the program.

On the other side of the spectrum is much more heavier system with one (Re)Actor per operating system process; these might be useful if we’re fighting with memory corruptions (either to debug them, or – in case of a buggy 3rd-party library which we have to use for whatever reason – to isolate them).

And, of course, between these two extremes (“everything in one single thread”, and “each (Re)Actor running in its own dedicated process”) there is pretty much everything else.

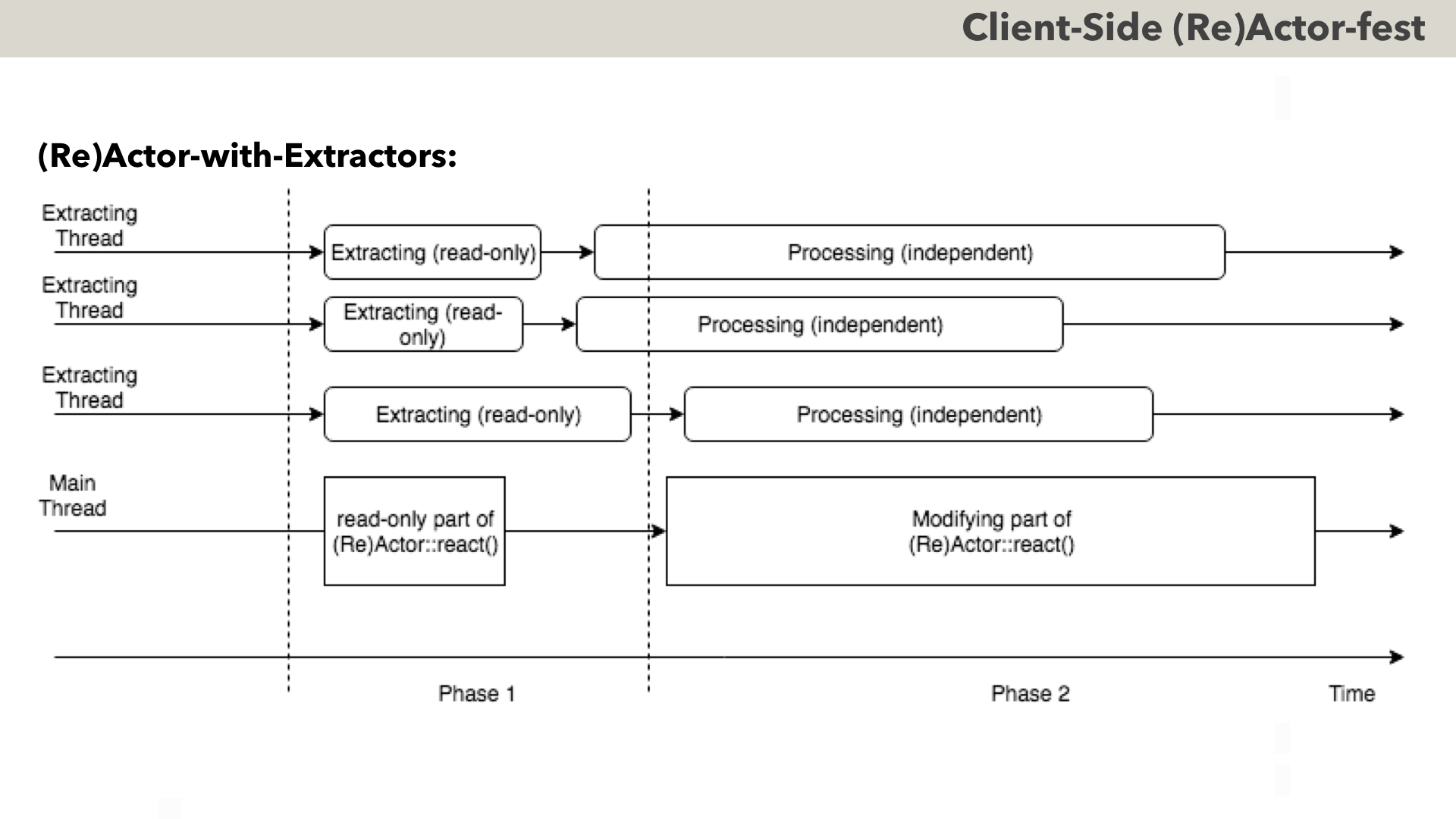

One interesting variation of (Re)Actors is a hybrid between Message-Passing and Shared-Memory architectures; I prefer to name it “(Re)Actor-with-Extractors”.

To the best of my knowledge, (Re)Actor-with-Extractors was first used by Bungie for their AAA game “Halo:Reach” [Tatarchuk]. The idea behind (Re)Actor-with-Extractors is simple:

- essentially, we have two phases in the processing (in games, both these phases usually fit into one single frame).

- during phase one (between dashed lines), state of our (Re)Actor stays CONSTANT (just because all the parties agreed not to modify it); as a result – it is perfectly safe to read it from multiple threads. In particular, “Extractors” may “extract” information-which-they-will-need-for-further-processing.

- as soon as each of extractors is done with extraction – it notifies Main Thread that it is done, and can process extracted data in its own thread, with no interaction with the state of our (Re)Actor.

- and as soon as ALL the extractors are done extracting data, Main Thread can proceed with modifying part of the (Re)Actor::react() (or the whole (Re)Actor::react() if we didn’t separate its read-only part).

This way, we can mitigate that Huge-State-Problem mentioned before (instead of separating it to multiple interacting (Re)Actors) – all while keeping ALL the benefits of (Re)Actors (there is NO thread sync within react(), it can be made deterministic, etc. etc.).

(Re)Actors-with-Extractors are known to be used in real-world (at least in gamedev industry) – however, I’ve seen them only on the Client-Side (my guess is that it can be attributed to an observation that ANY shared-memory approach cannot possibly scale beyond one single box, which is rarely sufficient for the Server-Side).

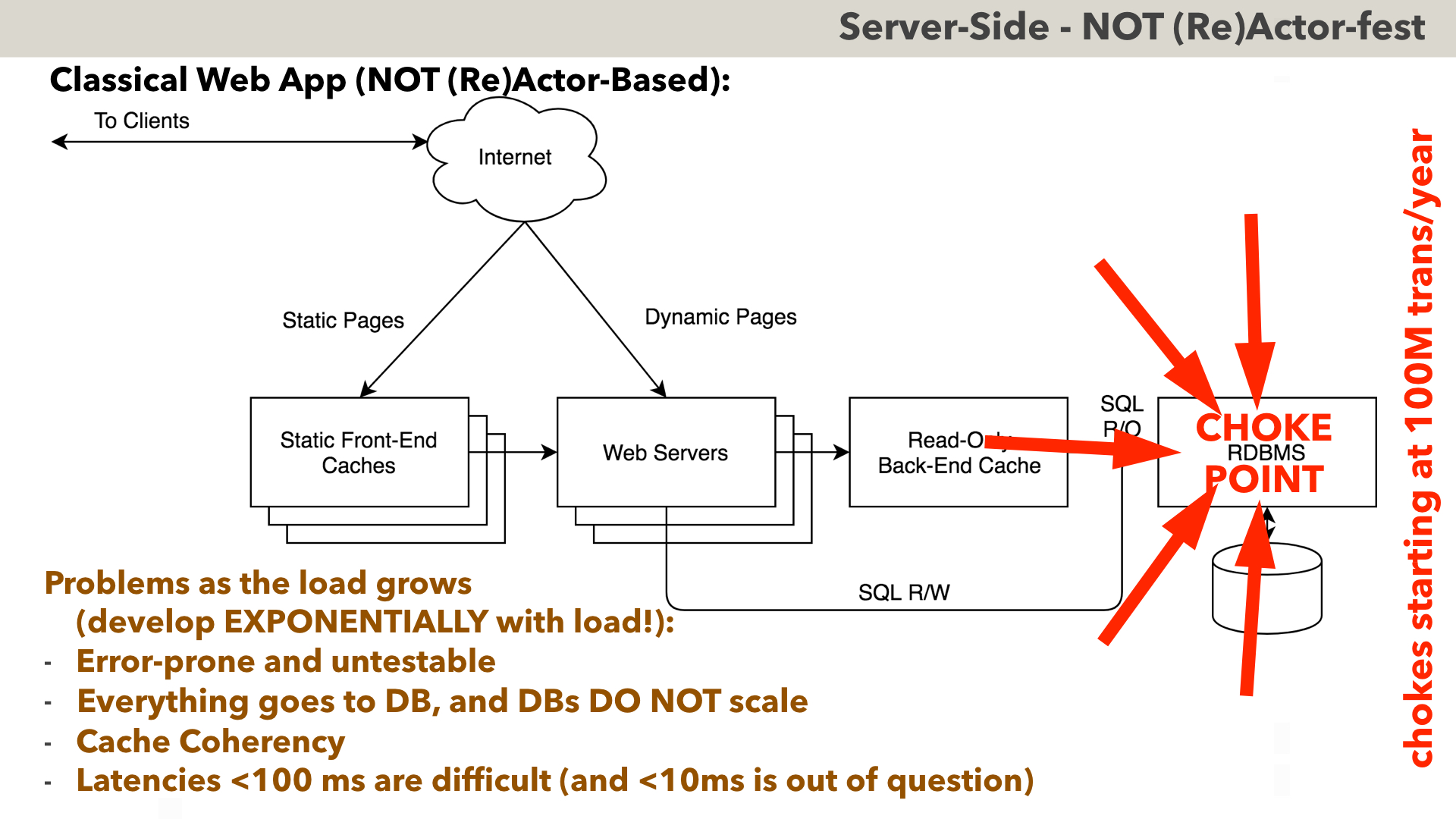

On the Server-Side, things tend to be even more interesting. Let’s start with a classical (NOT (Re)Actor-based) Server-Side for your usual web app.

The whole point of this architecture is that ALL the state we have is stored in the database. It means that EACH AND EVERY USER CLICK MODIFYING SOMETHING (beyond purely Client-Side stuff) – has to go to the DB. Since time immemorial, it was argued that this architecture, being stateless on the app side, BOTH allows for fault tolerance (which it does), AND scales well (which it doesn’t). The problem with the scalability of this architecture is that while scaling stateless apps is indeed trivial, it goes at the cost of pushing ALL the load to the database, and pushing all the load to one single point is rarely a good idea scalability-wise.

Practically, while this architecture does work for not-so-loaded projects, there are three big problems with this architecture as the load grows.

first, as the load grows, in the DB we will have to use “transaction isolation levels” different from “serializable” (for performance reasons); and going into non-“serializable” isolation, in turn, happens to be about as error-prone and fundamentally untestable as multithreaded programming. This includes ALL THE SAME issues such as explicit locking to avoid data races (which is known as “SELECT FOR UPDATE” in database world), and ensuring order of locks system-wide to avoid deadlocks.

Second, when we’re throwing ALL the data we have, at one single DB, no RDBMS out there scales in a linear fashion. In other words, DB becomes a CHOKE POINT of the whole architecture (and we have NOBODY to blame for it but ourselves). I have seen plenty of real-world examples of this problem, but the best publicly available one is a well-known problem of Uber, which first migrated from MySQL to Postgres (in hope to fix scalability issues), only to migrate back two years later or so. However, none of those migrations was really necessary: as we’ll see a bit below, Uber just doesn’t have enough write-transactions-which-HAVE-to-be-durable to cause any trouble even on a single(!) box; it is merely a question of architecting app with scalability in mind instead of blindly following stateless-app model pushed down our throats for last 20 years.

Third, there are cache coherency issues. As SQL writes go directly to RDBMS, bypassing back-end cache, it makes back-end cache not really coherent (which tends to cause quite a few visible-in-end-user-space issues); and attempts to make it coherent at app-level are EXTREMELY error-prone (as Phil Karlton has reportedly said: “There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.”).

And last but not least, latencies of the order of dozens of milliseconds or less are very difficult to achieve. As EACH AND EVERY writing request MUST go to DB – it has to go all the way to DB and back (and DBs are not known for being latency-friendly, especially under high load).

To make things even worse, these problems tend to develop EXPONENTIALLY as the load grows in the linear fashion. In other words – your DB will fail to cope with load (or even worse – exhibit that-multithreading-like problem in your code which never manifested itself before – EXACTLY on your BIG DAY :-(.

Very roughly, speaking of a single DB where trivial partitioning doesn’t exist, as long as you have fewer than 100 millions transactions per year – there is not much to worry about even in this architecture.

Between 100 million and 1 billion write transactions per year (with each transaction handling on average 10 rows) – things become MUCH worse. First, LOTS of previously-unseen transaction-isolation bugs start to surface – as noted above, in a non-linear fashion; and second – it starts to require LOTS of boxes as DBs do NOT scale linearly (that is, unless trivial sharding exists, but as soon as we have at least SOME interactions-just-because-user-A-wants-to-interact-with-userB – it doesn’t).

Between 1 billion and 10 billion transactions/year – things become even worse (to the point of this architecture becoming barely manageable).

And beyond 10 billion write transactions per year – with these architectures, things tend to become REALLY bad even IF (like with Uber) data is inherently trivially shardable.

Of course, all the numbers have to be taken with a HUGE grain of salt, and even in the very best case are accurate only within an order of magnitude.

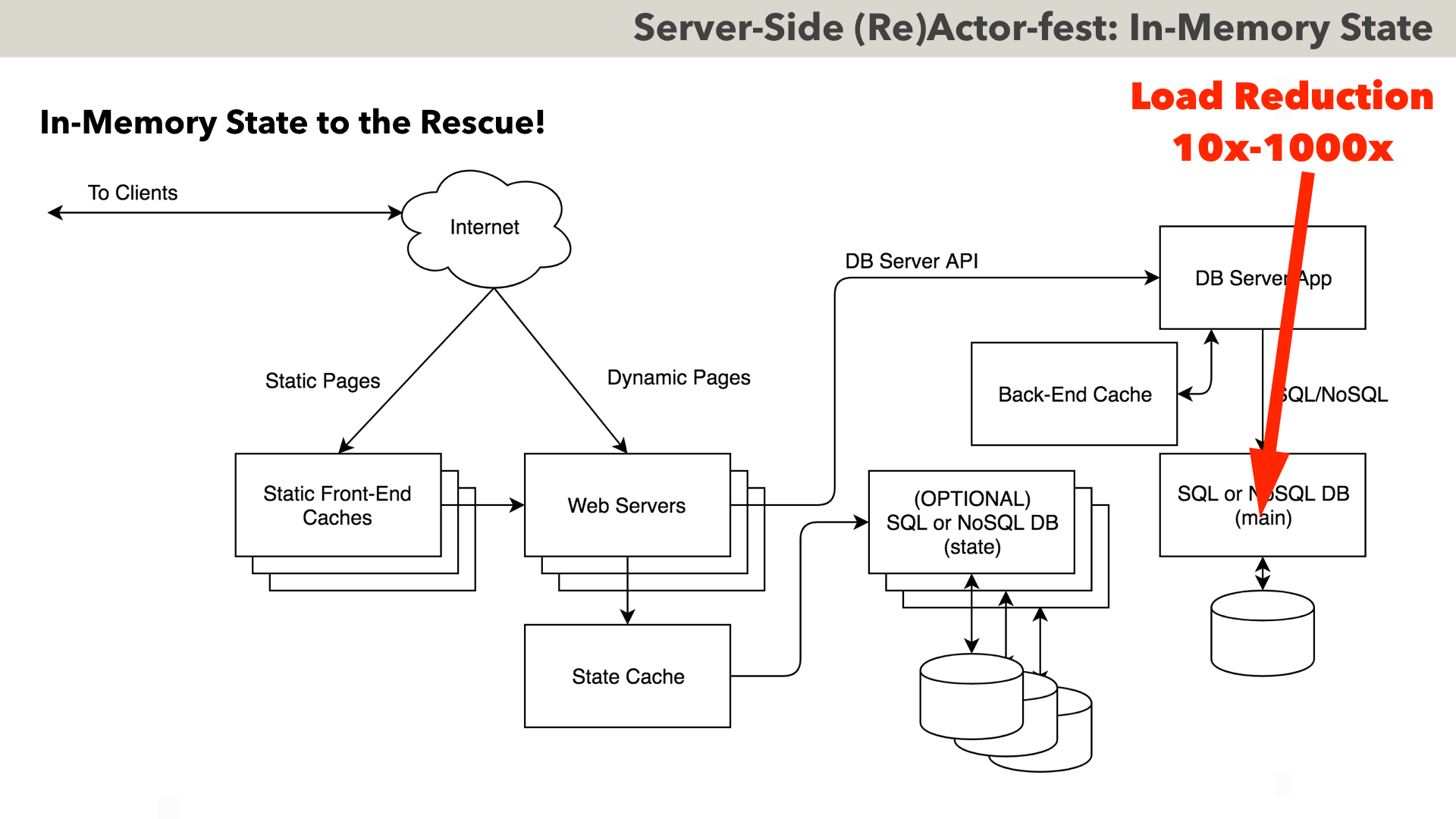

As no single non-trivially-shardable DB can realistically handle over roughly 10 billion transactions per year, there is pretty much the only thing we can realistically do to cope with this kind of load – introduce an in-memory state (at least as a write-back 100%-coherent cache).

Such an architecture is shown on the slide; what we REALLY need to do at app-level, is to decide which parts of our Server-Side state MUST be durable (i.e. MUST NOT be lost even if the whole thing goes down), and which parts of the state can be NON-durable – which means that the sky won’t fall if we lose them during a once-per-several-years crash.

For example, for Uber, it is only RIDES (and maybe ORDERS) which MUST be durable (and with the number of Uber rides being less than half a billion per year – load-wise there is absolutely nothing to speak about, it is certainly possible to handle this kind of load on one single core).

What causes most of Uber troubles, is writing of all those location data from all the drivers and users – but it is NOT kind of data which has to be durable! That is, if, once in a year, this data is lost – well, it will amount to a 30-seconds delay, which is not TOO bad; note that this data MAY still have to be made persistent for analytical purposes, but analytics is a completely different story which we do NOT care about at this point (at least – we can be sure that losing 30 seconds of analytics once a year won’t cause too much trouble).

And as soon as we split our data into “durable” and “nondurable” – our architecture becomes very straightforward: we have web servers which deal with State Cache (which is NOT durable, so DB behind State Caches is actually OPTIONAL), and DB Server App, which is responsible for dealing with DURABLE and highly-critical data.

Under this architecture, the introduction of the State Cache allows to reduce the load on DB Server App – usually by a factor of 10x to 100x, which already makes HUUUUGE difference. In addition, as DB Server App is a SINGLE point of access to DB – it has an option to have a 100% coherent read-only Back-End Cache (which was seen to speed things up further by a factor of 10x, further reducing the effective load on DBMS by another order of magnitude).

As a result, by using an in-memory state, we can reduce DB load by anywhere from 10 times (which, due to highly non-linear issues, already qualifies as A DAMN LOT) to 1000 times (which can easily solve all your problems forever-and-ever – even if you’re Uber, Facebook, or Twitter).

Oh, and from the end-user point of view, there are absolutely no coherency issues (we do NOT have any non-coherent caches in the picture, except for static stuff).

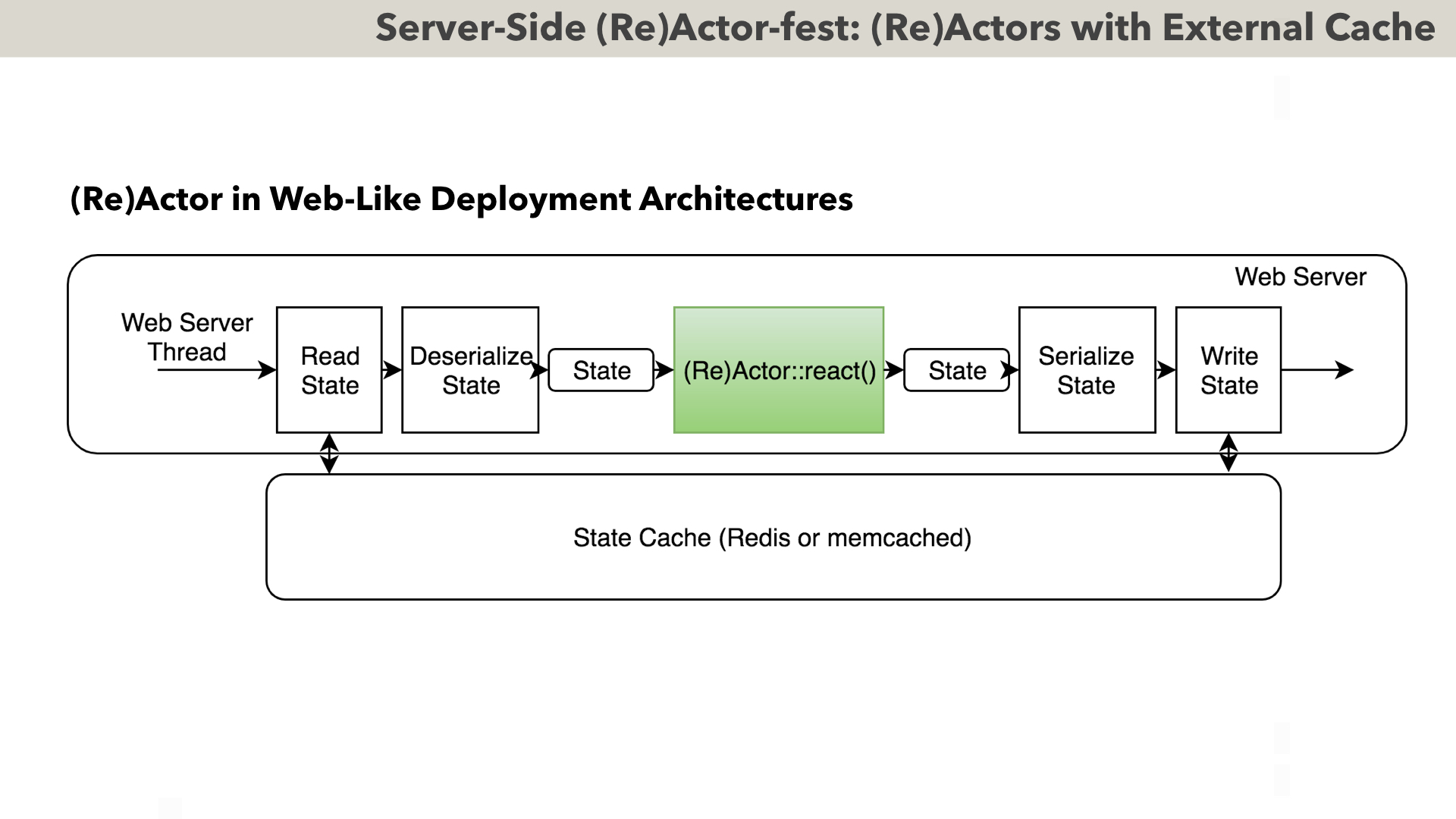

From our current perspective, the most important point of the previous slide is that as soon as we introduce in-memory state, we can already express business-logic as <da-dum! /> (Re)Actor (don’t tell that you didn’t see it coming).

Actually, Infrastructure Code running on our Web Server from the previous diagram, can perform the same thing which we already briefly mentioned in the context of different deployment options for our (Re)Actors. Indeed, nothing prevents us from storing the state of our (Re)Actor externally in Redis or memcached, deserializing the state before, and serializing it back after (Re)Actor::react() call. To ensure coherency, we’ll have to implement some locking (usually I tend to prefer optimistic one based on Compare-and-Swap by Redis/memcached), but this locking can and SHOULD be implemented completely by Infrastructure Code, and without ANY app-level logic involved (which IS important as changing Infrastructure Code is usually possible, while rewriting million-LoC app-level logic is usually a non-starter).

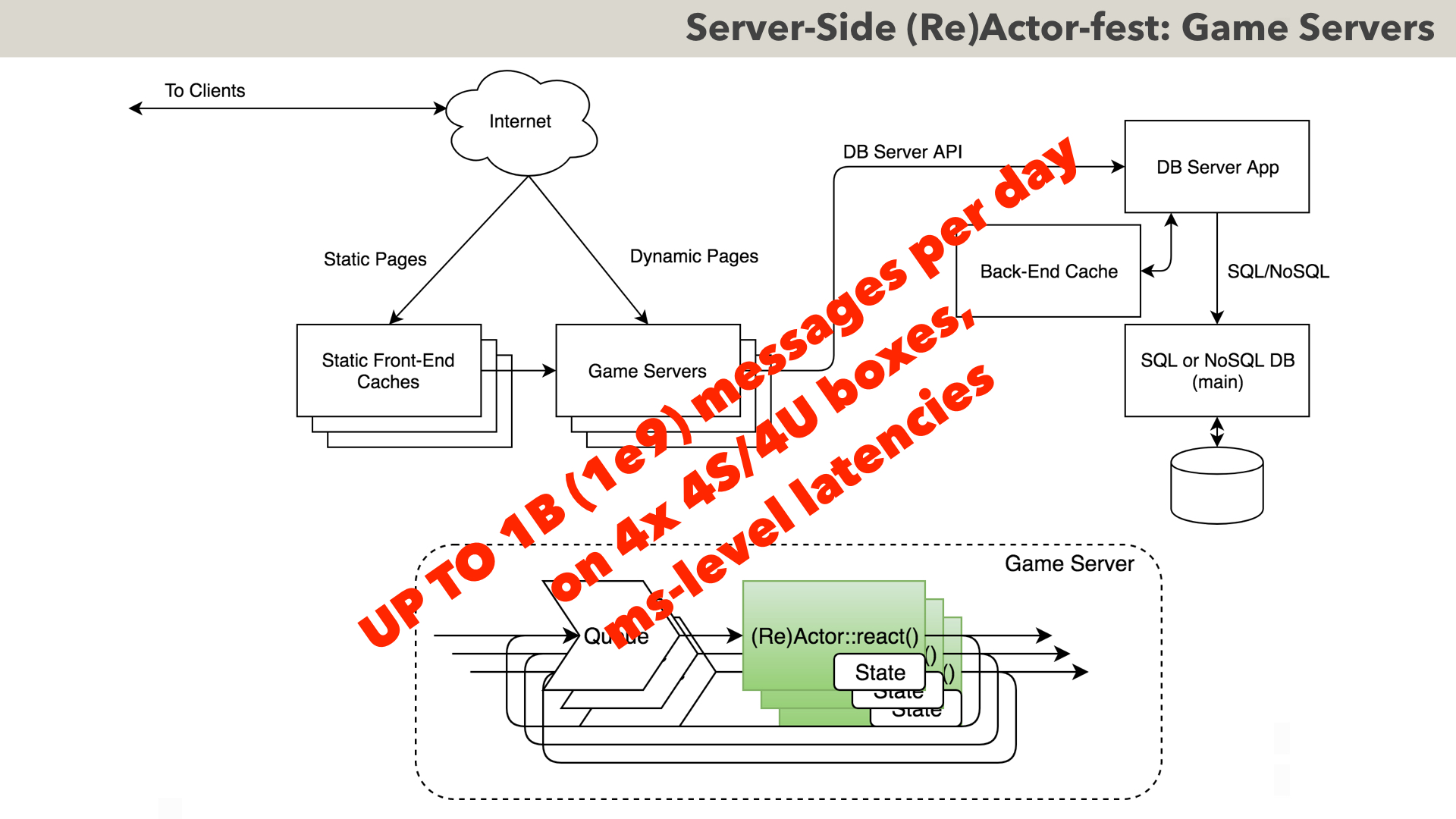

And as soon as we introduce in-memory state and (Re)Actors, moving further becomes a cinch. Here is how a typical MOG game server looks like (with Game Servers running classical (Re)Actors). BTW, quite a few stock exchanges look about the same (while for stock exchanges all transactions have to be durable, they still benefit from reduced latencies, effectively using (Re)Actors as read-only caches).

Note that migration from/to our previous diagram can be implemented without ANY changes to our (Re)Actor code (in other words, whether we want to use an external central cache such as Redis, or intra-(Re)Actor state, is a DEPLOYMENT-TIME DECISION).

As for real-world performance and scalability – such a system has been observed to handle a billion messages per day on mere four server boxes (though this number does not account for two dozens of stateless Front-End Servers to handle purely communications traffic); as for latencies – it has been seen to achieve latencies at single- to double-digit millisecond levels.

By this time, we got a perfectly-debuggable and very-reliable (Re)Actor-based system; however, a question “how to scale our database” remains; while it IS ten-to-a-thousand-times easier to scale than usual stateless web-like architectures, for really-loaded systems it still CAN become a problem.

Strictly speaking, DB Server App is an implementation detail, so to stay within the (Re)Actor-fest model, we are NOT required to implement it in any particular manner.

However, USUALLY, I am suggesting to go the route of gradual development of the DB Server App, where DB Server App is implemented as (no surprise here) a yet another (Re)Actor. While it does sound as an Ultimate Fallacy for anybody with traditional DB experience, it DOES work in the real world for several systems which have already processed hundreds of billions (that’s 11 zeros) of durable write transactions and made some billions of dollars to the respective companies in the process.

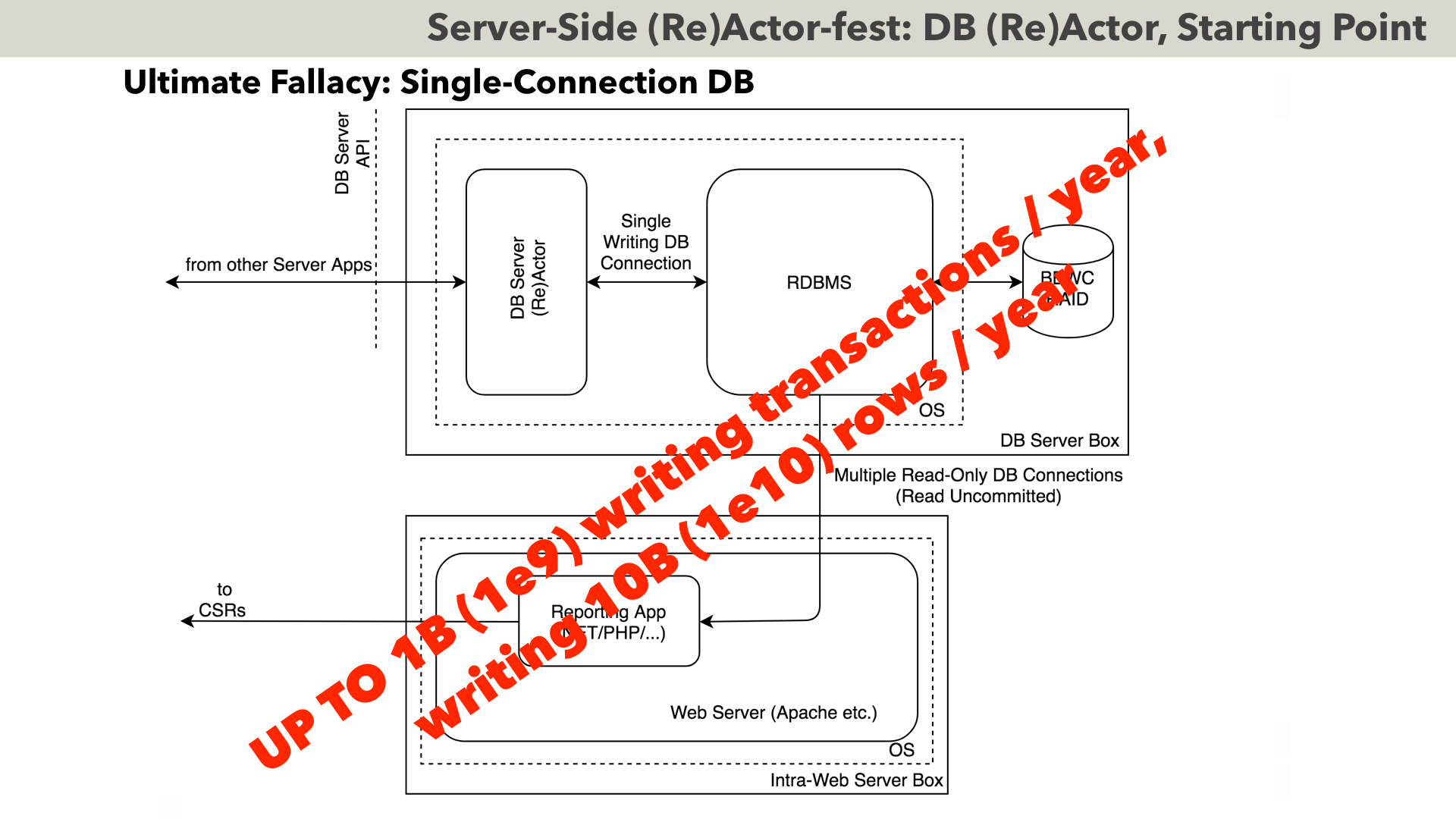

The very first step on the road to hundreds of billions of durable transactions looks as follows. Here, we have a DB Server (Re)Actor, which processes all the incoming requests one-by-one, over a single writing database connection; note that all the requests coming to DB Server (Re)Actor have to be expressed in terms of business logic (such as “move money from account X to account Y”), rather than in terms of SQL. Also, ALL the requests MUST be inherently atomic (so there should be no half-baked transactions or, Codd forbid, cursors after the request is completed).

This allows us to process incoming requests in a (Re)Actor fashion, one by one, and without worrying about “SELECT FOR UPDATE” or deadlocks. It also tends to work very fast and very predictably (there is zero contention by definition, and unless some read-only connection managed to poison RDBMS caches, there is absolutely nothing which can delay our simple requests). Note that we CAN have multiple read-only connections (preferably – with Read Uncommitted isolation, to avoid locks-which-may-affect-our-DB Server (Re)Actor)

When deploying such systems (which are very sensitive to latencies), there is some not-so-usual trickery; in particular, at least for DB logs, we MUST use a local RAID array with a RAID card having so-called BBWC (battery-backed write cache). As soon as this is satisfied – the whole thing works like a charm, and is extremely reliable too: first, the whole thing is debuggable (and can be made deterministic), so ANY issue is identifiable and fixable VERY quickly – and second, even internal races within RDBMS are rather unlikely to manifest themselves (as we’re not using MOST of race-dangerous RDBMS features, bugs in them become irrelevant to our deployment); overall, one specific RDBMS was seen to crash as rarely as once-per-30-to-50-billion-transactions – that is, under this specific configuration (and FWIW, multiple writers, used in replicas, made the same RDBMS crash MUCH more frequently).

After usual DB optimizations such as indexes, proper DB-level caching, etc., such systems have been seen to process about 1 billion transactions/year. As the load grows beyond this number, this system has to be refined.

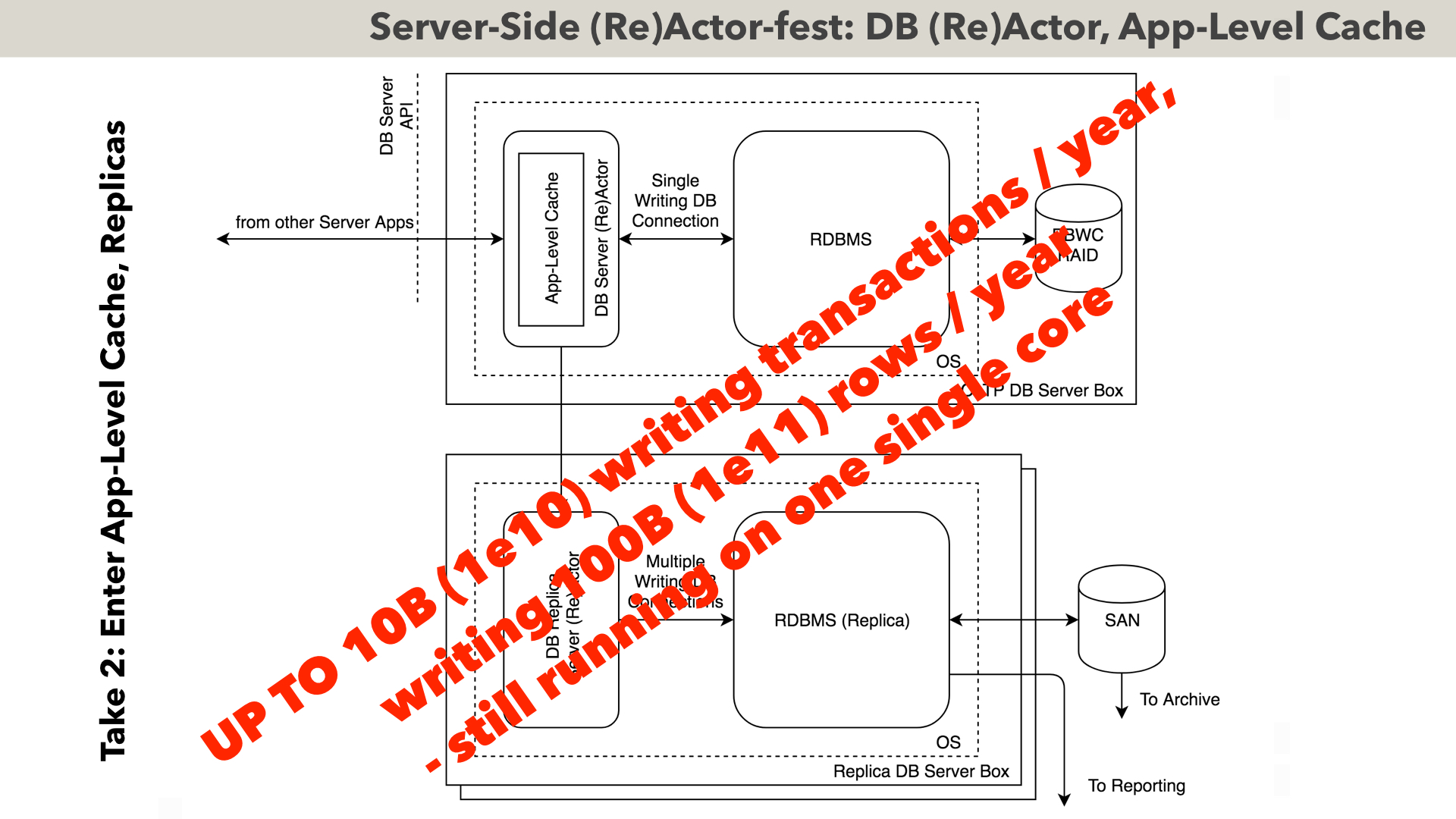

To support loads up to about 10 billion transactions/year (that’s 10 zeros), the following Take 2 (as a gradual evolution of the previous one) has been seen to do the trick. We still have our single-writing connection DB (Re)Actor, but – we’re doing two major improvements here.

First, as we have the single point of access to the database – we can have 100%-coherent app-level cache. This alone has been seen to improve overall performance by about an order of magnitude (especially caching USERS table tends to be beneficial, as there are traditionally LOTS of checks against this table while processing requests).

The second improvement is that instead of running reporting over the main DB, we’re creating a replica, and it is replica which is used to run reporting. This solves two problems: (a) it prevents cache-poisoning-caused-by-rogue-report, from ruining the performance of the main DB, and (b) it allows to limit the size of main DB (which in turn allows to keep it 100% cached, which is a Good Thing(tm)). Note that to limit the size of main DB, our replicas have to become “super-replicas” (i.e. when removing the historical data from the main DB, this data is still kept in super-replicas), but this has been seen working like a charm too.

Such systems (after LOTS of optimizations), have been seen to handle up to 10B transactions/year, writing up to 100 billion rows (that’s over ONE SINGLE DB CONNECTION, AND staying within the deterministic guaranteed-to-be-race-free processing).

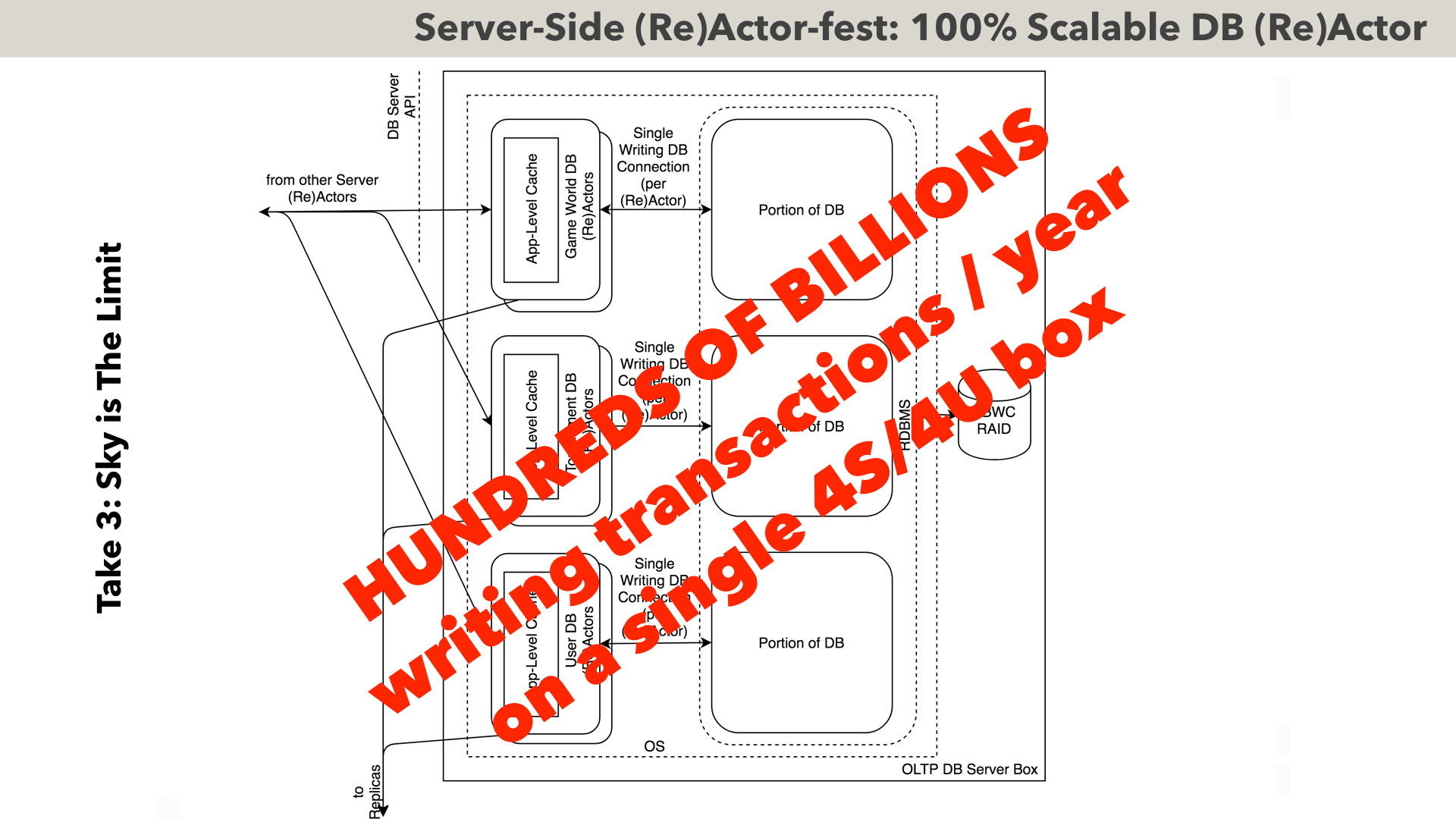

If even 10 billion durable writing transactions/year are not enough (which BTW I have seen in my career only once) – then we can go even further (while still staying within (Re)Actor paradigm). The idea would be to split our single monolithic database into multiple independent ones (it has been seen to work MUCH better than attempting to parallelize within the same DB).

The basic idea here is that when somebody wants to play, say, in a Tournament, first we’re making an ASYNCHRONOUS EVENTUALLY-CONSISTENT TRANSFER of the required attributes (such as “gold-required-to-play”) from USERS DB into respective TOURNAMENT DB, and then TOURNAMENT DB can do whatever-it-needs-to-do within its boundaries. When the tournament finishes – we’re doing another ASYNCHRONOUS EVENTUALLY-CONSISTENT TRANSFER from TOURNAMENT DB back to USERS DB. That’s pretty much it. As the transfers are inherently ASYNCHRONOUS – there is no blocking involved, so each of DBs still works at the maximum possible efficiency.

The way HOW EXACTLY to split DB depends on specifics (on the diagram, a split for a “typical” MOG is shown). OTOH, I don’t know of a system where such a split doesn’t exist. In particular, USERS table is present in a pretty much ANY business-like environment, and “places where users can interact” (on the diagram – “Game Worlds” and “Tournaments”) are also very typical. And as soon as we handled all the USERS and all the interactions between them – there isn’t much we have left; at this point the only thing we have to do, is to shard USERS horizontally (which usually becomes easy at this point, as all the inter-USER interactions are out of the picture) – and we have a PERFECTLY scalable database.

As for the performance – this kind of stuff can handle HUNDREDS OF BILLIONS OF TRANSACTIONS PER YEAR ON ONE SINGLE SERVER BOX. Of course, it WILL scale beyond one single box – but TBH, I know of ONLY ONE real-world system which really needs it; to put it into perspective – Twitter handles 200 billion tweets per year, and all Facebook comments+status updates+photos amount for 500 billion updates per year. The only system which goes above this level is post-2005 NASDAQ where lots of bot trading is happening, and which goes into single-digit thousands of billions quotes+trades per year.

Sure, one single box will NOT be sufficient to store THE HISTORY of all those transactions for more than a few months, so we WILL need historical super-replicas to store the history; however, for 100% COHERENT PROCESSING OF DURABLE TRANSACTIONS it will work (and this is THE ONLY place where we need 100% coherency, so everything else scales trivially).

On a question “hey, everybody is using those huge cloud clusters to handle the same kind of load, why?” I will tell that I don’t really know WHY. However, I can tell a real-world story in this regard. Once upon a time, in a certain online industry, there was an industry leader processing about 50% of the whole market; they made it on a bunch of 50 boxes or so (including both database and app servers). A direct competitor (with 99% of the logic being the same, and reporting available being MUCH weaker), had traffic which was about 4x lower AND used 400 boxes. That means that competitor used 32x MORE SERVER BOXES PER UNIT OF WORK. Moreover, downtimes of the industry leader were about 5x lower than the industry average. Needless to say, that at that point the industry leader was the only one in the industry using (Re)Actor-fest architecture (both at app-level, and at the database level).

Oh, and let’s observe that I DO NOT have ANYTHING against Big Data NoSQL databases: they are indeed REALLY GOOD for their purpose; it is just that they are NOT the best choice to handle durable transactions in a highly coherent manner; their best place is to handle that huge historical arrays of data stored in replicas.

Let’s summarise our findings of (Re)Actor-fest architectures:

- First, it IS possible to build a system using NOTHING but (Re)Actors at least at business logic level

- Second, such systems were seen to:

- scale to at least to 10 billion network messages a day

- (Re)Actor-based database handling can scale up to tens of billions writing DB transactions/year – that’s over a SINGLE DB connection

- there are systems which reached an equivalent of 100 billion writing DB transactions/year in testing, but AFAIK, the number has never been reached in practice

- in addition, (Re)Actor-fest architectures were observed to (a) have 5x less unplanned downtime than a competition, and (b) use 30x less hardware than the competition (for the same unit of work, that is).