We Tried That, Didn’t Work

We tried that, didn’t work #

Excerpt #

In our quest for making programming simpler, faster, and prettier, no logical fallacy provides as much of an obstacle as “we tried that, didn’t work”. The fallacy that past failed attempts dictates the scope of what’s possible. That just because someone, somewhere, one time attempted something similar and failed, nobody else should try…

In our quest for making programming simpler, faster, and prettier, no logical fallacy provides as much of an obstacle as “we tried that, didn’t work”. The fallacy that past failed attempts dictates the scope of what’s possible.

That just because someone, somewhere, one time attempted something similar and failed, nobody else should try. That lowering our collective ambition to whatever was unachievable by others is somehow good.

There would be no human progress if we all quit trying after any unsuccessful attempt.

This fallacy is bad enough when it talks about what hasn’t yet successfully been achieved, but it’s downright bewildering when it’s trotted out to refute the reality of what’s already been proven possible.

Take the example of building fast, modern web applications with #NoBuild JavaScript. We’ve been running HEY without bundling or compiling JavaScript for three years now (you can sign up and View Source to see exactly how!). We have tens of thousands of happy, paying customers, and we’ve made millions in profits from this product. Yet certain quarters of the dev discourse continue to insist what we’ve done isn’t possible. Wat?

It’s like insisting your map is correct even after it failed to record the massive mountain you’re literally staring at. Refusing to believe reality because it doesn’t comport to your mental model of the world is an intellectual failure state.

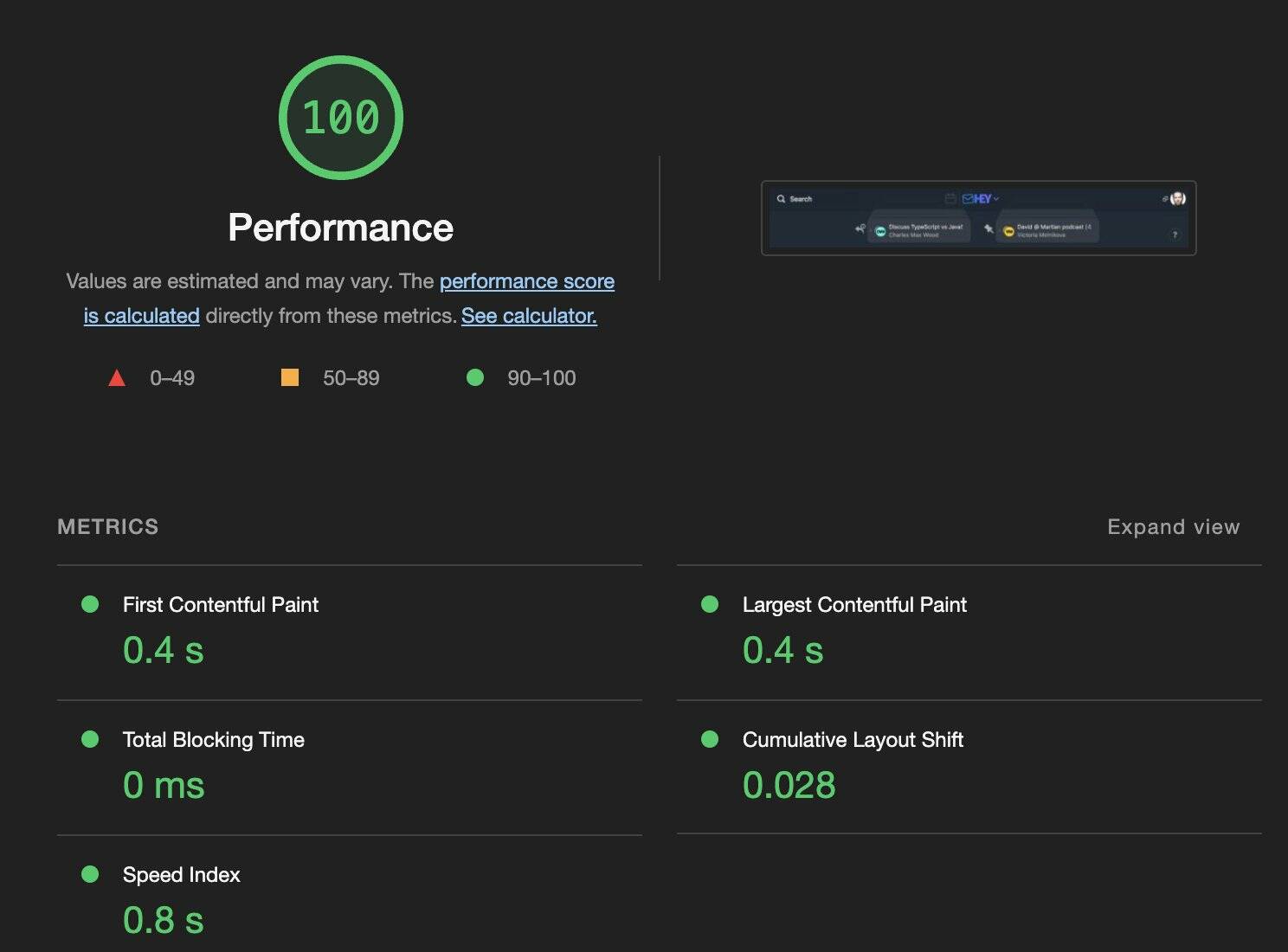

Part of that outdated mental map of what’s possible on the web includes the notion that #NoBuild JavaScript inevitably leads to slow applications. That you’ll drown in the waterfall of requests cascading through your dependencies. Here’s a report from Google’s web performance tool Lighthouse. HEY literally gets a perfect 100/100 score on performance:

Now yes, that’s because HEY is built differently from, say, Khan Academy or Vercel. We don’t have hundreds of dependencies or thousands of JavaScript files. We send about ~100 individual JavaScript files over HTTP/2, and only rely on a handful of external libraries, mostly Hotwire.

That’s how progress usually happens! By someone doing something different than whoever went before them in pursuit of the same goal. But instead of recognizing that, and perhaps becoming just a bit curious at how it was done, the “we tried that, didn’t work” fallacy sucks people into the small world of “can’t”.

Making programming better requires a willingness to test your priors. To question your assumptions. To recognize the half-life of facts. Yes, how we built HEY wasn’t feasible prior to 2020, before import maps opened the door. So if your mental model of the web is soaked in the possibilities of 2010-2020, I understand your skepticism, but please don’t let it restrict your ability to appreciate the progress happening now.

None of this is an argument that everyone should follow us into this glorious #NoBuild future. I’ve retired from trying to convince anyone who’s happily making stuff with other tools that they must change their ways. I’m sharing how we’re building HEY because it not only works, but works exceptionally well for us. Do with that testimony and technology as you please.

But when you’re building with small teams, or even alone, you need all the conceptual compression you can get. Nothing compresses what you need to know like removing an entire step from the equation.

That’s always been what excited my about building for the web, from Ruby on Rails through Hotwire through everything. Making programmers more effective by reducing the amount of moving parts they have to learn and wrestle with on the daily.

Don’t get stuck in the mud of complexity.