Tips on How Staff Engineers Can Impact Incidents

Tips on How Staff Engineers Can Impact Incidents #

Excerpt #

Staff engineers impact incidents by modeling transparent and productive, serving as incident commanders to coordinate response, and getting involved in retrospectives to address root cultural issues.

Key Takeaways #

- Staff engineers can provide examples of – and coach teammates in – productive behaviors like transparency, admitting knowledge gaps, and questioning assumptions to help prevent incidents.

- Bolstering a supportive, inclusive engineering culture provides another layer of defense against incidents. As culture stewards, staff engineers should continually invest in psychological safety.

- Staff engineers have the skills to excel as incident commanders during outages, including coordination across workstreams, communicating with stakeholders, and preventing responder burnout.

- Staff engineers should get involved in post-mortems to raise the quality of root cause analysis and push for pragmatic action items tied to culture gaps.

- Improving the underlying cultural issues prevents more incidents than procedural gates.

As a staff engineer, I recently led my team through one of the worst incidents of my career. In my talk at QCon SF 2023, I told the story of this situation. An infrastructure change introduced automation that ended up erroneously deleting critical customer data. It took us three days to fully resolve the outage and restore the data.

In retrospect, there were many things we could have done differently – from preventing the initial incident to improving our response process. This showed me that staff-plus engineers have an opportunity in all stages of the incident process to drive positive change.

The Incident #

At the company where this incident occurred, the infrastructure was managed via Terraform code. The Platform team (my team) reviewed and approved Terraform changes in PRs, but the changes were written by product teams. At the time, we had no centralized system for applying Terraform changes. This resulted in low transparency around what infrastructure changes were made, by whom, and when. This particular incident was caused by a small Terraform code change that enabled automation to expire and eventually mark data objects to soft delete after 24 hours. If we didn’t catch and fix the issue in time, it would then hard delete these critical customer data objects after another 24 hours.

Related Sponsored Content #

Introducing the Reliable Web App Pattern for .NET #

Digging Deeper into Building on LLMs, ChatGPT Programming, and Observability #

Microservices Versus Serverless #

Key Components of an Event-Driven Microservice Platform #

Amazon Web Services Cookbook: Recipes for Success on AWS (By O’Reilly) #

It took a day before our monitors started to alert us to the issue, and it was immediately customer-impacting. During the initial stage of triaging, we were able to stop the bleeding and prevent data loss, but inadvertently created a secondary incident, which unfortunately our customers discovered first. By this time, many of us working on the incident were tired or distracted, and there was no coordination across the multiple groups trying to solve issues.

It took a total of three days for senior and staff level engineers across most of our teams to restore the damage done, affecting almost every part of our platform. It was a confluence of issues and missteps that, when combined, allowed this change to slip through.

Contributing Factors #

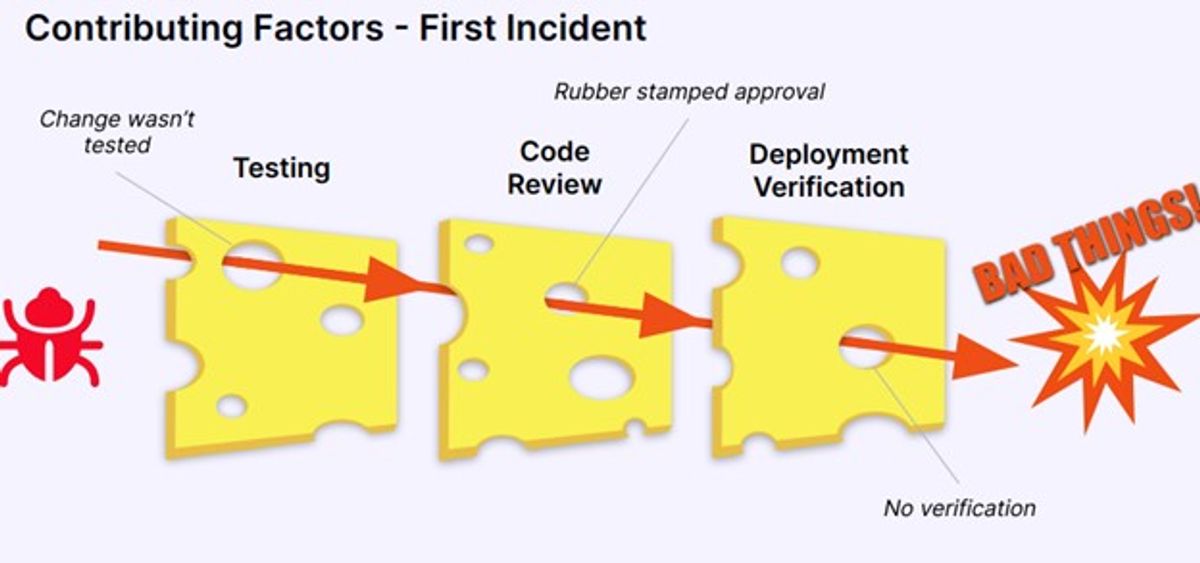

The Swiss cheese model is a metaphor often used in risk analysis or root cause analysis to demonstrate the need for a multi-layered system approach to security or safety. I first learned about this model when I was working at the Kennedy Space Center for the shuttle program, and safety there was paramount in everything we did. When applying this model to software incidents, each slice of cheese represents a layer of our defenses against an incident.

With the initial incident, while we had layers of defense set up to protect ourselves from an incident, the holes all aligned, allowing this issue to slip through:

- Testing - the change wasn’t tested in a pre-production environment first to verify it worked as intended.

- Code Review – the change was approved in the code review without any questions or discussion.

- Deployment Verification - the change wasn’t verified after it had been deployed to production to make sure it was working as expected.

Cultivating Culture as a Defensive Boost #

We already had a supportive and inclusive culture. However, no environment is perfect or even static. A great culture can still have blind spots, which was the case for us. There’s always room to continue to put care and feeding into your culture. It’s never perfect and it’s never done. As technical leaders, you can be the champions for attending to that culture.

Looking back on the incident, it’s possible that bolstering the supportive culture would have provided more coverage in our defenses. As a technical leader, I can model productive behaviors – working transparently, admitting knowledge gaps, relentlessly gathering information, and questioning assumptions. And I can coach teammates to do the same. Improving safety nets enables engineers to produce their best work.

Testing and Culture #

The author of the change knew the importance of testing as a best practice. From later discussions, I learned that they didn’t know how to put together an appropriate test plan for this change. Digging deeper, we discovered that this change was in an unfamiliar area of the system for the author. We could then ask, why didn’t the author ask for help if they were unfamiliar and didn’t know how to go about testing this? Unfortunately, we didn’t ask the author why they didn’t but can speculate that the author may not have been comfortable asking anyone for help.

Digging into the contributing factors of this discomfort, without knowing why they felt that way, can be challenging. This is an important aspect of any organization’s culture that requires constant care and feeding. Staff engineers have a lot of influence here. Any time spent asking, “How can we make our peers feel more comfortable asking for help?” and following up on those changes is well worth your time. We can surmise that if the author had known they should have tested their changes and felt comfortable reaching out to get help, the incident possibly could have been prevented.

Code Review and Culture #

Simply requiring code reviews is insufficient. Reviewers may not speak up with questions or concerns even if they don’t fully understand the changes. I admit that I was one of the reviewers, and didn’t ask questions, or investigate even though I knew that the change was on a critical piece of our platform. I was concerned about the code but was unwilling to admit to my new team that I didn’t understand the potential impact. If I had asked questions, if I had had the courage to be vulnerable, and show that I didn’t know something publicly, maybe that conversation could have helped us prevent this incident.

Solving this problem of people not feeling comfortable asking questions, or admitting when they don’t know something, is not easy. This is a human psychological issue. You can create the most supportive, inclusive environment, and people may still feel uncomfortable or insecure at times. As leaders, we should always be working to improve the environment to be as inclusive for everyone as much as we can.

Deployment Verification and Culture #

Looking at the deployment verification layer of defense, we can ask why the author didn’t verify their changes after they were deployed. While we didn’t get to that question specifically in our post-mortem, I can guess that there weren’t clear expectations on how to verify. This, compounded by the author’s lack of understanding how to verify their change in the first place, most likely led to no deployment verification at all. Here’s another opportunity to look at improving our culture to buffer our defenses.

It could be baked into the culture that development and testing best practices are frequently shared, and expectations are made clear as to what tasks are the responsibility of the developer or author to meet the definition of done. Staff engineers can play a big part in establishing this. They can model this behavior as well as overseeing and coaching their teammates to follow these best practices.

Overseeing Effective Incident Response #

Once the incident began, stress levels and urgency to restore service meant responders were reactive in their behavior, without much coordination. We lacked an empowered incident commander maintaining vision on the big picture. Poor handoffs caused duplication of effort across fragmented workstreams. Fatigue led to gaps in coverage. Some people took break without clearly sharing when they’d be back online.

Incident Commander role #

Staff engineers have the experience to step in as incident commanders. Keeping emotion at bay, bringing structure, pushing for regular progress updates, and escalating appropriately allows for those fixing issues to stay heads-down.

We didn’t always have an explicitly identified person serving as the incident commander. When we did, that person was also deep into triaging, troubleshooting, and fixing. They were too focused on their own work. This made it very difficult for them to be able to adequately look at the big picture, manage updates, and communicate with stakeholders, or pull in the right help when it was needed.

We also didn’t have anyone coordinating schedules, expectations, or deliverables. People were just self-volunteering for things or not, logging on and off whenever they chose to, without explicitly handing off work or communicating their planned schedules.

A staff engineer is a great candidate for volunteering to assume the incident commander role. You don’t even need to be on the impacted team. In fact, it might even be better if you’re not.

An incident needs someone that can keep their head above the tree line and on the big picture. An incident commander can gather status from those that are working heads-down, and handle the communication with the stakeholders, thus allowing the hands-on folks to stay focused on their work. They can work on coordinating and removing blockers. They can make sure there’s clear communication and expectations as to who’s working on what, what their schedule and plans are. If there needs to be a handoff, the incident commander can ensure that’s done as well.

The incident commander can also advocate for themselves. If you’re the incident commander and you need a break, or you’re no longer the best fit for the role as the situation changes, you can ask for someone else to relieve you and take over command. No one should be hesitant to assume command thinking they’ll be stuck with it for the duration. Any of the roles and responsibilities throughout the incident should be able to be fluid as the situation changes. We just need to be explicit when those things change. And setting that example for the rest of the triage team is a great way to encourage an environment where people can step away with the appropriate notification and handoff.

These are all skills and capabilities that fall into the wheelhouse of a staff-plus engineer. Having an effective incident commander can really make or break the success of the incident response.

Driving Lasting Improvement via Post-Mortems #

After resolution, a blameless post-mortem process can unearth valuable insights. It certainly helped us. But learning degrades without proper follow-through on action items. Here again is an opportunity to provide pragmatic leadership – facilitating robust conversation without judgment, and orienting solutions based on a thorough root cause analysis.

We use an incident management automation tool, and we have a template that autogenerates the post-mortem document. And we’ve got guidelines and a format for conducting the post-mortem debrief meeting. We even start each post-mortem debrief meeting reading the retrospective prime directive to remind everyone of our blame-free focus:

“We run a blameless incident process, meaning that we do not search for or assign blame or even attribute causes to individuals. Regardless of what we discover, we understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job they could, given what they knew at the time, their skills and abilities, the resources available and the situation at hand.”

Recently, we’ve noticed that people running these debrief meetings were just reading the template and going through the motions. They were checking the box that they’d held the debrief meeting and wrote the post-mortem doc, but the quality was low. There was little effort made on the root cause analysis, or retrospecting over the incident management process. There were few action items, and those that were identified were often forgotten about or not followed through with.

This is an example of how culture can make the difference over process. Adding process wouldn’t have helped us have more effective post-mortems – we already had a lot of process. People were going through the motions in these meetings, not because they were lazy, but most likely because these engineers were new to managing and facilitating retrospectives, and they didn’t know how to drive those conversations. The true gaps were environmental and cultural.

As shepherds of engineering culture, staff engineers should seize the critical growth opportunities that incidents provide. We own continuous improvement, and progress compounds when built upon enhanced safety, trust, and resilience. Even if you aren’t running the meeting, you can ask probing questions. You can show curiosity without judgment. You can model and direct root cause analysis. You can help determine pragmatic solutions for action items.

Even if you weren’t directly involved in the incident, as a staff engineer, you should attend post-mortem debriefs and read the documents so that you can influence the process and help raise the quality of the output. An incident is a critical opportunity to learn lessons and identify improvements that could be made. Staff engineers’ involvement can help make that happen.

Root Cause Analysis #

Within the post-mortem debrief, it’s critical to perform a thorough root-cause analysis. This can help identify actions that may prevent similar incidents from occurring in the future. However, when we’re performing a root cause analysis, we shouldn’t stop at the first contributing factor. We need to retrospect on each contributing factor and keep asking why until there are no more answers. That’s when we’ve hit the root cause. When you perform this level of analysis, what you often find is that there’s something about the environment or culture that contributed to a given hole in our defense layer. As a technical leader, you have a prime opportunity to spot cultural gaps that allow incidents and determine ways to address them. Improving the culture for engineers is ideal, rather than layering on processes that could hurt productivity.

Conclusion #

You can’t prevent all incidents from occurring with improvements to your engineering culture, but you can reduce the number of incidents, and dramatically improve the time to resolve those incidents. You can model, foster, and encourage a learning culture, where questions and vulnerability are acceptable. You can serve as an incident commander and have many opportunities to improve the incident response. When incidents do happen, you can help get them fixed effectively and efficiently. You can improve the quality of the post-mortem process. You can drive the solutioning of action items to best fit the improvements needed to improve your environment and prevent similar incidents in the future.

About the Author #

Erin Doyle #

Erin Doyle is a Staff Platform Engineer @Lob. For the last 20+ years prior she’s been working as a Full Stack Engineer with a focus on the Front-End. She’s also an instructor for Egghead.io and given talks and workshops focusing on building the best and most accessible experiences for users and developers.

Show more