The Fermi Paradox of Ideas by Luca Rossi Refactoring

The Fermi Paradox of Ideas 👽 - by Luca Rossi - Refactoring #

Excerpt #

A handy mental model to reflect on business ideas, build vs buy, and aliens.

Hey 👋 this is Luca! Welcome to a ✨ monthly free edition✨ of Refactoring.

Every week I write advice on how to become a better engineering leader, backed by my own experience, research and case studies.

You can learn more about Refactoring here.

To receive all the full articles and support Refactoring, consider subscribing 👇

A few weeks ago, while having a beer with some friends, the discussion turned to one of my favorite concepts: the Fermi paradox about extraterrestrial life.

I don’t pretend this is the stuff we discuss regularly — in fact, we rapidly went back to our nerdy zeitgeist around tech and startups. But the things were somehow connected, and I kept thinking at how Fermi’s argument could be used for much more than aliens.

But let’s recap the original paradox first 👇

In the summer of 1950, while walking to lunch, Enrico Fermi discussed recent UFO reports with a few fellow physicists.

The conversation turned to the apparent conflict between the high estimates on the existence of extraterrestrial life, and the lack of obvious evidence for it.

Fermi argued that even with the slow kind of interstellar travel that is within reach of Earth technology, it would only take between 5 and 50 million years to colonize the galaxy. This is relatively brief on a cosmological scale, and since there are many stars older than the Sun, and since intelligent life might have evolved earlier elsewhere, you have to wonder why the galaxy has not been colonized already.

Even if such colonization turned out to be impractical or undesirable, we could still see signs of intelligence from a distance. Chances are advanced civilizations should be visible within the range of today’s observable universe.

With no evidence of such intelligent life in places other than Earth, it must be that some step in the evolutionary process is very unlikely, and prevents the vast majority of settings from moving further.

In other words, there must be a great filter that sits somewhere between the presence of a habitable planet, and the galaxy colonization stage by a civilization born and raised on it.

Several great filter candidates have been proposed over time, like abiogenesis, resource exhaustion, or global catastrophes.

Crucially, as humans, we should hope to be already past this filter, whatever it is. We should root for the filter to be one of the stages we already went through, like the creation of life (the most accredited candidate), or the emergence of tool-using intelligent animals.

This is why many scientists argue that finding life on Mars would actually be bad news for humanity. If life is so common that we find it even on nearby planets, the great filter is likely to be still ahead of us.

Nick Bostrom, Director of the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford, explained it better than I do, in 2007:

Ok, but, as amusing as it might be, why are we talking of aliens on Refactoring?

I believe the Fermi paradox is a great mental model you can use in other situations too — which arguably more useful, for the rest of us, than extraterrestrial life. My favorites are:

💡 Evaluating business ideas

🔨 Build vs buy decisions

Let’s say you have an idea for building something new. Something that makes people solve a pain (or, better, do a job) 10x better than they do today.

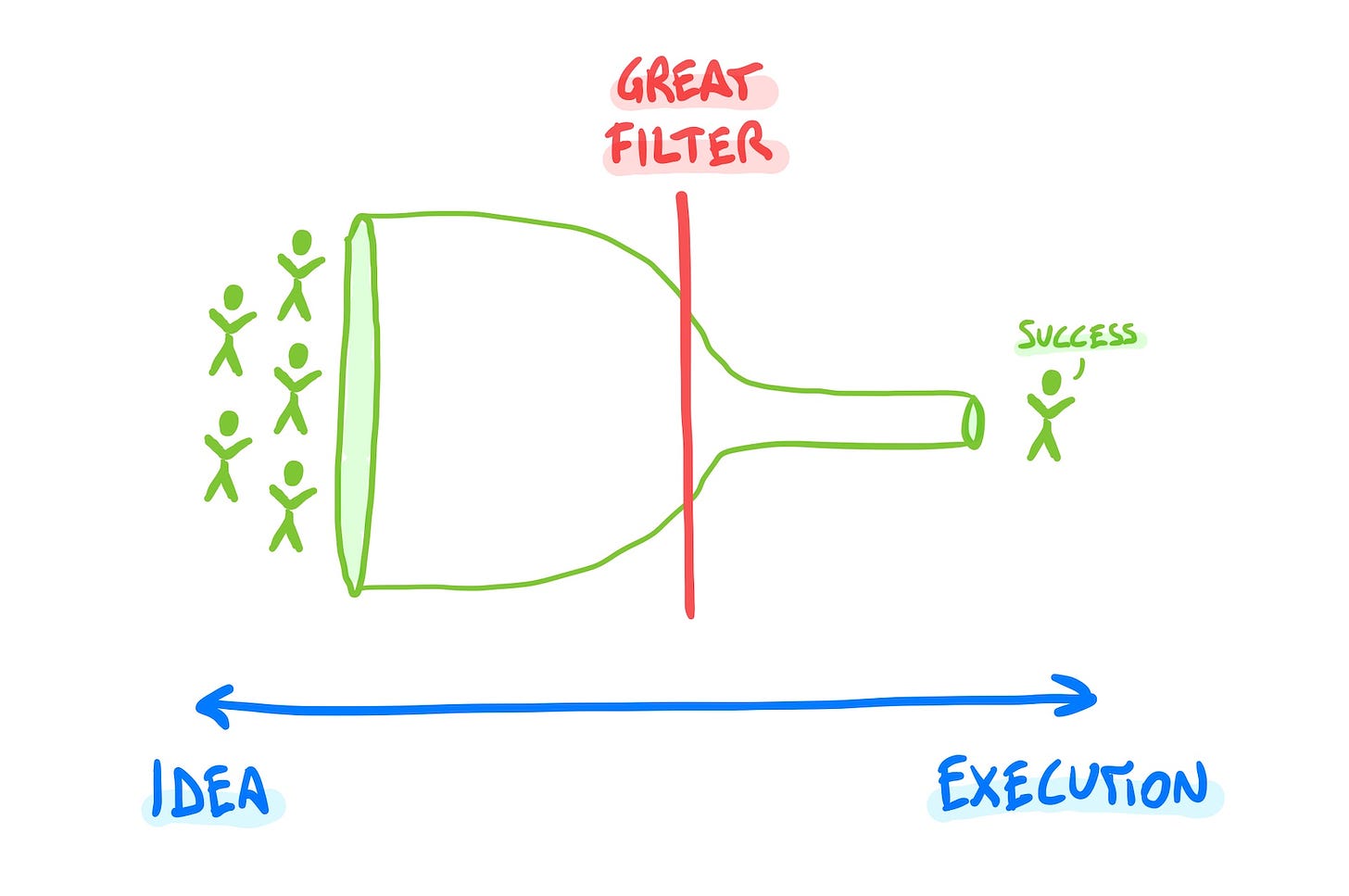

You may ask yourself: why doesn’t it exist already? If this is a great product / business, where is everybody? Like Fermi, we have to conclude there is a great filter somewhere that prevented this product from being created so far.

To get a hint of where such great filter is, one useful trick is to check what other people think of your idea.

If your idea looks good to most, you should conclude that many other folks will have had the same idea, but failed somewhere. There will be a great filter at execution time that makes things hard.

[

One example of such ideas is Uber. Everyone falls in love with the idea of summoning cabs anywhere, but very few people have the chops to deal with labor, regulation, low margins, and the issues about scaling in the various markets.

Viceversa, if your idea looks bad to most people, it may very well be that the great filter is at the idea stage itself. There are no successful products because very few people think they are worthy of being built.

Of course, most ideas that look bad do so because they are bad indeed. However, as Paul Graham famously wrote, there is a sweet spot for good ideas that look bad, and these are arguably the most promising ones.

The first time Peter Thiel spoke at YC he drew a Venn diagram that illustrates the situation perfectly. He drew two intersecting circles, one labelled “seems like a bad idea” and the other “is a good idea.” The intersection is the sweet spot for startups.

– Paul Graham

Today, when I tell people I quit my job to write a newsletter, they are puzzled. I do my best to explain Refactoring to them, but most do not get it, or make a face that makes it clear they think it’s a bad idea.

I used to be concerned about it, but now I am slightly thrilled when people react this way. The less people get why I do this, the higher the chances I am already past the great filter.

It works the other way too — when many people tell me that my idea is good, well, that might be bad news. Just like life on Mars.

A while ago I also stumbled upon this tweet by Camille Fournier:

This is basically the Fermi paradox of internal tools.

Let’s take aside your core tech, as you are always going to build by yourself what makes you unique and is a core asset to your company.

But when it comes to operations and internal workflows, SaaS products and low-code solutions are so advanced today that building bespoke code is an exception to the rule.

So to reframe the great filter question: if this product should be useful to other businesses too, why hasn’t anyone built it yet?

Three answers come to my mind:

This is extremely common, because looking for good tools to buy / integrate is harder than it seems.

In my experience, your best strategy about it is to nurture your network so you can eventually ask peers what they do in similar scenarios.

You can (and should) also leverage communities for the same reason. Shameless plug: check out here how a startup CTO was recommended multiple tools to solve his problem on the Refactoring community.

Maybe there isn’t anything that works straight out of the box because it is easy to build it with Zapier and a few automation tricks.

You can also try Parabola or Integromat for different automation flavors.

If you can exclude the first two solutions, and it is not related to your core business, you should really ask yourself why no one else needs this — as Camille points out.

Basically, don’t be the Glass Sword man.

From time to time I am happy to promote great tools I think you may be interested in 👇

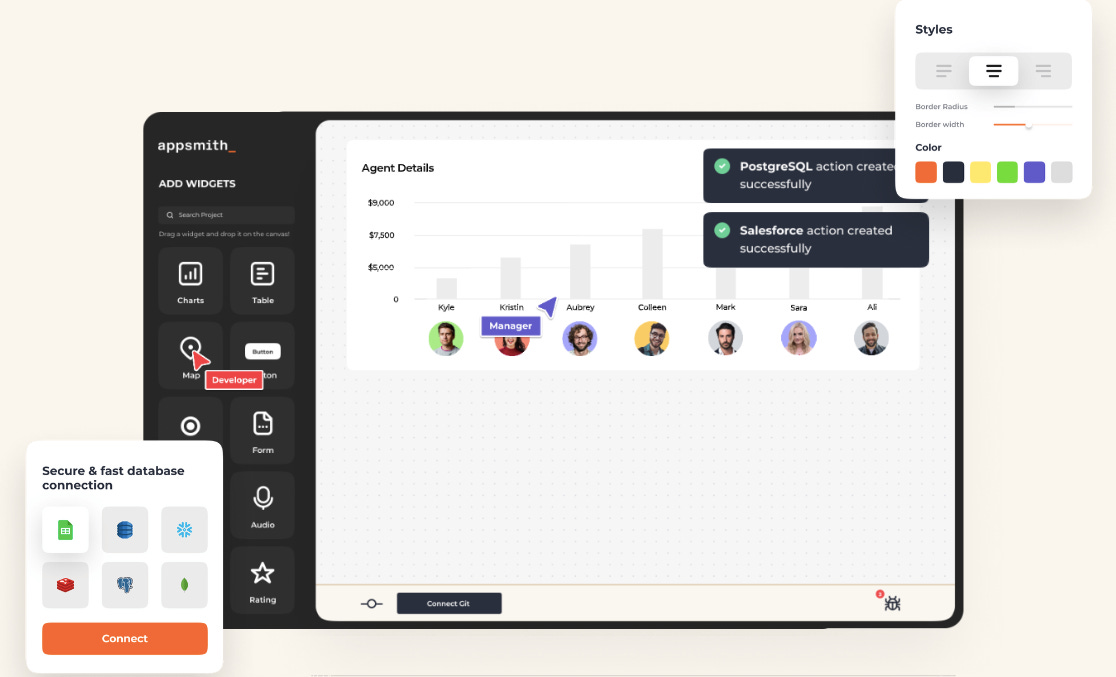

Talking of build vs buy, you should really look into Appsmith.

[

Appsmith is an open-source framework to build internal applications quickly and easily. You can plugin any database or data via APIs, use an ever-increasing list of UI components, and write business logic using Javascript.

I discovered it a few months ago, talked with founders, and I was impressed by how powerful and easy to use it is.

Appsmith folks would love to send across some great swag for the first 100 Refactoring users, as well as give you a pair-programming session with their engineers. Sign up for that here 👈

📑 Why is it so hard to decide to buy? — This great article by Camille Fournier exposes our most common biases about the infamous build vs buy decision.

📑 In the Great Silence there is Great Hope — Famous essay by Nick Bostrom where he argues why we should hope not to find any signs of life on Mars, or any nearby planet.

📑 Black Swan Farming — seminal essay by Paul Graham about the counterintuitive nature of investing, and startup ideas.

Amazing • Great • Good • OK • Meh

Subscribe to Refactoring #

Weekly, practical advice on writing great software and working well with humans.