Test Driven Daydreams Dev Community

Test-Driven Daydreams - DEV Community #

Excerpt #

My thoughts on Test-Driven Development (TDD) have certainly… fluctuated over time. At this point,…

My thoughts on Test-Driven Development (TDD) have certainly… fluctuated over time. At this point, it’s far from being a new concept. Wikipedia traces its origins to the early 2000s. I believe that I first heard of it about a dozen years ago. During that time, my personal exposure to it has varied wildly from one company to the next.

This is not my pro-TDD fanboy article. Nor is it my click-baity anti-TDD rant. Rather, I’m writing about it now because I think I’ve settled on an approach to TDD that works for me. Of course, your mileage may vary…

TDD Fanboys #

My first “problem” with TDD, similar to problems that I experience with almost any other approach to dev, is that it spawns its own legion of fanboys. Granted, this is true of sooooo many other aspects of software development. But if you’re trying to have a calm, rational discussion with someone about TDD, it’s nearly impossible to do so with those who’ve already drank the TDD Kool-Aid.

So while I know that these points will do absolutely nothing to quiet the TDD mouth-breathers, I’m still gonna point out a few basic facts:

TDD is not a “cure-all”.

You can be a great developer without ever worrying about TDD. You can be a crappy developer who adheres tightly to TDD. TDD can be a great tool. Just like a hammer can be a great tool. But that doesn’t mean that it’s the “right” tool for every job.TDD is too often confused with general concepts of unit testing.

Writing unit tests does not (necessarily) mean that you’re following TDD. Having X% of test coverage does not qualify (or disqualify) you as doing TDD. And doing TDD doesn’t solve the ongoing questions of exactly what should-or-should-not be tested within a given codebase.

The above facts are not meant as any kinda “take-down” of TDD. But I’ve grown a little tired of hearing the TDD fanboys talk about it as though it solves many issues around testing - that it doesn’t really solve at all.

The Challenges of TDD Groupthink #

Most of my qualms haven’t been with the concepts of TDD. They’ve been with the difficulty in getting everyone on a team to adhere to those concepts - or to even agree on what those concepts are. I’ve been in some shops where TDD was talked about like an unreachable dream. I’ve been in others where it was presented as some kind of standard, that we all should be following, and then… no one followed it. I’ve been in places where it was openly agreed that we would be implementing TDD - and then those guidelines were blatantly ignored as soon as we faced the first pending deadline.

I’ve also seen scenarios where an underlying desire for TDD “purity” culminated in abandonment of the approach altogether. For example, some believe that the “right” way to do TDD is to have someone else write the original tests, before you begin writing the code that would adhere to those tests. And that approach isn’t “wrong”. But it requires a lot of coordination and team cohesion. And when that coordination fails to materialize… everyone just drops the whole TDD idea and goes back to doing things as they did before.

Let me absolutely clear on this: I’ve been in several different shops where TDD was discussed/proposed/championed, but I’ve never been in a dev shop where it was actually implemented as a regular practice. And I’ll also be honest here and admit that, when the rest of the team easily abandoned their TDD dreams, I tended to fall inline with the group.

I also wanna be crystal clear in saying that I’m sure there are dev shops out there that rigidly adhere to TDD. I’m not claiming that they don’t exist. I’m just stating that, in my anecdotal experience, TDD is frequently talked about, but has rarely/never been truly implemented.

Going It Alone #

One of my recent “aha” moments was around the idea that I don’t need to have Full Team Buy-In in order to do TDD. In other words, if Joe and Mary on my team don’t bother with TDD, that doesn’t mean that I can’t still write my code with TDD. In the past, I tended to see this as a team-centric decision. And to be frank, it is better if the whole team is aligned on something like this. But that doesn’t mean that everyone has to be in lockstep.

That may sound like I’m advocating for you to “cowboy” your way through the dev process. But I think it’s perfectly reasonable to say, “This is the way that I know to write high-quality code. So this is the way that I’m going to attack this problem.” In practice, there are many aspects of dev where I enforce my own personal coding standards. For example:

If I’m building a new database-driven app/feature, I start first with the database. I design the database schema (or, at least, I ensure that I fully understand the existing schema) before I ever begin writing the first line of code. I don’t ask others if they want me to do it this way. I don’t worry whether the others will design their features with the same approach. For me, I know the best way to get the feature built. So I just go about doing it that way.

Similarly, if I’m integrating with web services (or, if I’m building those web services), I always ensure that I have an up-to-date Swagger file (or other endpoint schema model) before I begin writing the code that will consume those services. If others don’t build their code in the same way, that’s fine. But I’m not going to abandon the best way that I know to deliver quality code simply because others eschew those methods.

So my point here is that, while it would be great if your whole team was on the same TDD page, you don’t need to confine TDD to being a team-level decision. If you find that you are writing better quality code by using TDD methods, then do it.

Contract-Driven Development #

Another recent “aha” moment, for me, has been that, IMHO, TDD isn’t really test-driven development, it’s contract-driven development. What do I mean by that??

Well, in the examples above, I explained how I don’t start building a database-driven application until I’ve either designed the database schema, or I at least understand the existing schema. Because the data layer, in many respects, defines what your application can-or-cannot do. So if you’re trying to build features without understanding the underlying data model, you’re probably setting yourself up for some nasty rewrites down the line. If I’m integrating with endpoints, the same concept applies.

But what about when you’re writing code that doesn’t directly hit a database or an endpoint? Is there any particular data contract that you need to be aware of? Yes.

Almost all code contains a proliferation of smaller code bits. Those “bits” are typically called methods, or functions, or components. Methods / functions / components all share some common features. Specifically, each one expects zero-to-many inputs, and they all return zero-to-many outputs. Those inputs and outputs are… your data contract.

When you first started coding, you probably began by cranking out functions (or methods, or components) where the inputs-and-outputs where defined “on the fly”. You added new inputs (arguments) as needed. And you added new outputs (return values) as needed. And when you were done, hopefully the function did what you wanted it to do.

TDD flips that equation around. It forces you to define (and thus, think deeply) about exactly what those inputs/outputs should be before you ever begin writing the function. In other words, TDD forces you to define the data contract for a function before you ever write the function.

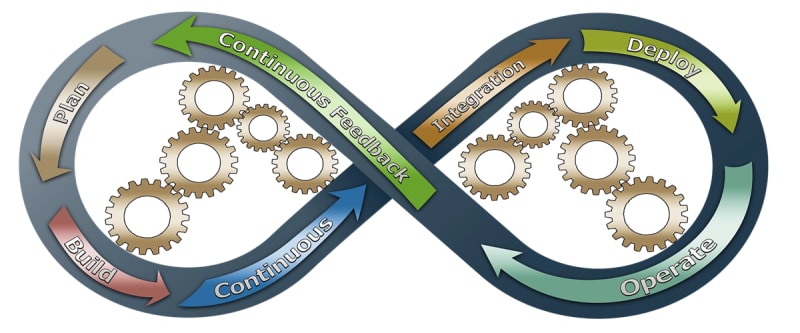

Continuous Feedback #

TDD has another benefit that I believe is rarely discussed. This benefit is that of continuous feedback. If you’ve worked in any professional dev environment, you’re probably accustomed to feedback. You receive it every time you submit a pull request, or any time your team does broader code reviews. If you’re accustomed to pair programming, you may also receive live feedback in real-time.

But coding is often a solitary experience. Unless you’re doing a live coding session, your first real feedback on any piece of code often comes at the point when you feel your code is completed and you’re submitting it to be reviewed/merged. But if you’re following TDD, you start to receive that feedback from the moment that you begin coding.

By defining the tests first (tests which should, initially, fail - until you complete the code), you’re defining, upfront, a data contract. And then, as you write that code, the tests continually tell you whether or not it passes. This is doubly useful once you move on to refactoring your code.

While there’s nothing inherently “wrong” about coding outside of TDD, there are some worrisome behaviors that often exist when people are coding without it. For example, most non-TDD devs don’t even bother to run the tests until they’ve “completed” their code. Only once they notice that something’s failing (and thus, they can’t commit it) will they start to pay close attention to the tests. But TDD devs are much more likely to have the tests running during the entire time that they’re coding. They do this because they’re constantly getting “feedback” on the code that they’re writing - and they can correct errors much earlier in the process.

Non-TDD devs are also much more likely to craft tests that encompass cognitive biases. (Specifically, confirmation bias.) They write code. Then they slap some tests on it. And do the tests pass? Of course they do! Because, whether they realize it or not, they’ve written tests that are designed to pass what they’ve written - rather than writing tests that are designed to confirm the desired functionality.

In this model, the tests are not providing continuous feedback. They’re only providing “feedback” after-the-fact. Even worse, this “feedback” too-often only serves to confirm what the dev has already coded.

Time Crunches #

The biggest problem that standalone TDD advocates run into is: the time crunch. There’s been a lot of research that indicates that, in the long run, proper adherence to TDD should save you and your team time. But in the short run, TDD practices can feel like a burden.

Any time you need to spend significant effort pre-planning your work, that’s an additional time burden. If you’re writing your tests first, and you’re putting in significant effort to ensure that those tests are meaningful and helpful, then that absolutely qualifies as “pre-planning”. So it is possible that, on at least some of your tasks, a TDD approach will make you look slower in the eyes of your fellow devs. This is especially true if those devs don’t follow TDD practices.

Consider the following potential scenario:

Your team hasn’t adopted TDD as a standard. Of course, you can still write your code with TDD. But sometimes the difference in approaches will be apparent as you work through a sprint.

Imagine that Joe is on your team. He can’t be bothered with TDD. You’ve both been given tasks of similar scope, each estimated to take a day of effort.

Joe finishes his task by noon. Joe’s actually a really good developer, and his code looks fine. (Remember: Being a non-TDD developer doesn’t mean that you’re a bad developer, despite what any TDD fanboys may claim.) At the end of the day, you haven’t quite finished your task, and you let your team lead know that you’ll need a little more time before you submit the code.

Is there a risk here that you’ll come to be seen as something of a “lesser” dev? Well, to be perfectly frank with you, the answer is “Yes”. If the broader team doesn’t embrace TDD, and all they see is that Joe finished a task, estimated at one day, in half a day, and you completed a similarly-estimated task in more than a day, this could lead some to hold you in less regard. But honestly, if that’s the way your team judges work, then you may need to think carefully about whether this is the right fit for you long term.

Of course, over time it should become apparent to your colleagues that your methods yield solid code that’s prone to fewer reworks. But I also wanna be frank with you: Some shops will focus, myopically and brutally, on nothing but raw time.

But I’d encourage you to think about it this way:

If someone wants me to start developing an endpoint-driven application, but they can’t/won’t give me the schemas I can expect from those endpoints, and they won’t let me develop the endpoints myself, then I’m simply not going to start cranking out code just to satisfy someone who wants to know that I’m coding. (Even if that coding is blind.) I simply won’t do it. And if that causes a problem with my team, I’ll find somewhere else to work.

Similarly, when you’re adhering to TDD, you’re taking the time to define your own data contract, upfront, before you ever begin the “real” work of coding. You shouldn’t be afraid to follow that approach. And if that causes ongoing problems on your dev team, then you really should consider finding a team that will support quality coding.

TDD As A Personal Directive #

In conclusion my central point is that, previously, I always saw TDD as a team-based decision. We either adopted it for the entire group - or we didn’t, and I ignored it altogether. But it doesn’t have to be like that.

There are many aspects of dev where I’ve learned, over years of experience, what works best for me to deliver quality code. When I encounter those scenarios again, I don’t ask someone’s permission to write the code in the best way that I know how. I simply do it.

TDD can be that type of personal directive. Yes, it would be ideal if everyone on your team feels the same. But if you find that you can write much better code by using TDD, then… do it.