Diy Geoengineering the Whitepaper Nephew Jonathan

DIY Geoengineering: The Whitepaper - Nephew Jonathan #

Excerpt #

The how, for those sick and tired of litigating the why

It hit 96 degrees when I started writing this post (that’s about 35.5C for the rest of you)—in the DC area, in September—so let’s talk geoengineering (the how more than the why). This post is intended as something of a sequel to/commentary on Casey Handmer’s post We should not let the Earth overheat! from a couple months ago, and/or a summary/crystallization of some Twitter discussion from a few weeks ago. If you haven’t read Casey’s post, it’s strongly recommended.

Why should we geoengineer?

Because I don’t like the idea of dying in a 120-degree heat wave and degrowth means the worst depression in the history of industrial civilization. Next question?

I don’t think we have enough data to know that this is safe.

Nobody seemed to care very much about the potential consequences when we suddenly phased out sulfur emissions in shipping. Here’s what we’ve seen since then:

[

Were “stakeholders” consulted? No, we just went ahead and did it.

So we shouldn’t have phased out sulfur emissions in shipping?

I’m saying that tradeoffs exist for any policy action taken, and pausing/reversing global warming is no exception. Geoengineering will have side effects. Institutional paralysis (i.e., hand-wringing about the potential side effects of geoengineering until we’re at 2C above preindustrial levels and have no choice) will have worse side effects.

(There are, of course, reasonable concerns about the correct approach that we’ll look at later in this white paper. My point is that I’m not interested in engaging with people whose answer to every problem is to drown potential solutions in paperwork and “community input” meetings.)

This doesn’t abolish capitalism.

And thank goodness.

My two previous main post series, on Anki use and hydrogen generation, started from the basics and worked their way up to the solution. The results were pretty long-winded, so I’m going to do the reverse for this white paper by presenting a solution and then dissecting it. 1 The solution is this:

Global warming, though not ocean acidification, is quickly and cheaply reversed by ejecting calcite nanoparticles (with an average radius in the ~90nm range) into the stratosphere, using a propeller-based system to prevent particle clumping. The particles should be carried up by hydrogen balloons, and very preferably released over the tropics. The total amount needed will be on the order of several hundred kilotons yearly, and the total cost should be somewhere between $1B and $5B yearly.

Let’s go through this piece by piece.

Global warming is quickly and cheaply reversed by ejecting calcite nanoparticles into the stratosphere.

This is an approach known as stratospheric aerososol injection, or SAI. Essentially, the Earth is absorbing too much electromagnetic radiation from the sun due to increased concentrations of carbon dioxide and other gases (which you knew). One way to fix this (which we’ll need to do long-term) is to sequester atmospheric CO₂ somewhere other than the air (I wrote a long article for Works in Progress on my preferred approach, which involves grinding and milling silicate rocks into silt and dumping them in ocean water). But sequestering enough CO₂ to make a serious dent in the amount we’ve added since 1750 is an expensive, long-term project (on the order of trillions, over several decades), and until we can get that up and running, we’ll need to keep a lid on global temperature rise.

So in the immediate term, rather than drawing down carbon to decrease the amount of energy absorbed, we’ll need to decrease the amount of energy that hits the atmosphere in the first place. That’s where SAI comes in: use particles of a highly reflective substance to bounce light back into space.

Why calcite, and why an average radius of 90 nanometers?

Calcite is the most common form of calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), which you may recognize from the white cliffs of Dover or a pack of sidewalk chalk.

[

Calcite macroparticles. The colored ones have had dye added.

It’s excellent at reflecting light at the most common wavelengths produced by the sun, and—

CaCO₃ only has a refractive index of about 1.6. Titanium dioxide’s RI is 2.5; let’s use that instead.

There are multiple variables we need to pay attention to, not just reflectivity/refractive index; calcite is pretty close to a Pareto optimization on the most important ones.

Let’s take a look at Pope et al. 2012, who take a look at the Pinatubo eruption of 1991 (which pumped enough sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere to cool things down for a couple years) and explore options for repeating its effects with other substances. It’s not just the refractive index that matters; particle size does, too. If we look at figure 2, we’ll see that the optimal particle size (usually given as the average radius) is a bit under 1 micron 2.

[

While titanium dioxide is more effective than calcite, it’s also more expensive. Calcite’s maybe $50 a ton, though you’ll really need to get the particle size right; TiO₂ is about forty times pricier.

The bigger issue, though, is stratospheric heating. Reflective substances don’t reflect every wavelength equally; there’s a range of wavelengths they’ll absorb or reflect, and an absorbed wavelength turns into waste heat. (This is what causes global warming in the first place—CO₂ is quite good at absorbing wavelengths the sun produces a lot of. It’s also why we think of infrared wavelengths as ‘heat radiation’—they’re not heat in and of themselves, but organic molecules like those found in humans or reptiles are very good at absorbing them.)

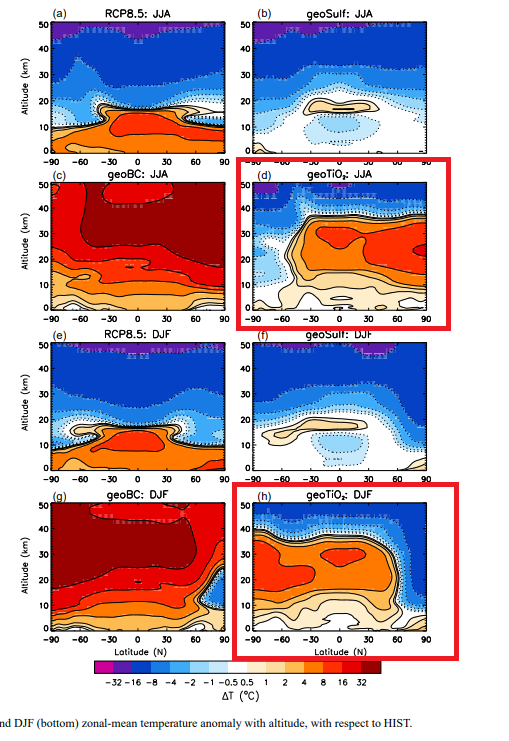

TiO₂ is great at reflecting the visible light that represents the lion’s share of what the sun gives off, but it’s also very good at absorbing UV wavelengths. While this might sound like a good thing, what it means in practice is that stratospheric TiO₂ particles will cook the stratosphere. Here’s figure 2 from Dykema et al.:

[

Rutile and anatase are both forms of titanium dioxide, but rutile’s the more reflective type.

And here’s a simulated result for TiO₂, though unfortunately not calcite, from figure 10 of A. C. Jones et al.:

[

I’m not entirely sure why sulfate (geoSulf) doesn’t produce as much heating here as Dykema et al. imply it should; my guess is that it has to do with particle size, which we’ll talk about in a bit. At least we’re not using black carbon (geoBC)!

Calcite has one other major virtue, which is that it’s alkaline and can scavange ozone-depleting gases from the ozone layer. These tend to be very strong greenhouse gases, as well. More on this here.

You know, calcium oxide has an even higher refractive index of 1.83, and is even better at scavenging greenhouse gases, including stratospheric CO₂.

I imagine the particle size is going to change a bit when CaO turns (via calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)₂) to CaCO₃ 3, but this is a possibility. Empirical data are needed to see what happens when you use CaO; calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) has a refractive index about equal to that of CaCO₃. Water vapor acts as a greenhouse gas, especially at high altitudes (remember Hunga Tonga?), so the conversion of CaO to Ca(OH)₂ is likely to cause cooling for this reason as well. (There are only about 1.5 gigatons of water vapor in the stratosphere to begin with; we can skip the CaO if we want to avoid scrubbing too much of it out). CaO and Ca(OH)₂ are also more alkaline than CaCO₃ and should be better at scrubbing GHGs; you’ll also cut down on payload since every kilo of CaO can react to form 1.75 kilos of CaCO₃.

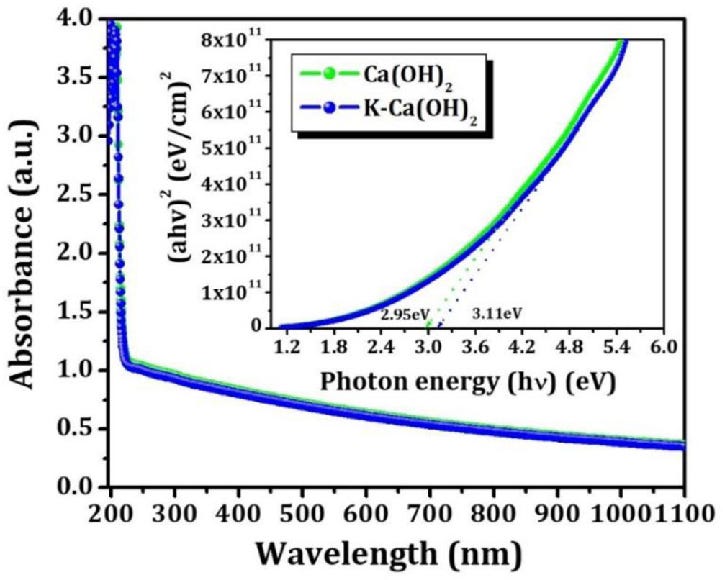

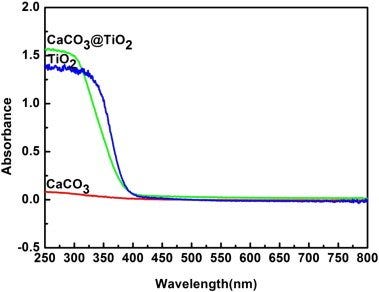

On the other hand, the UV absorption spectrum problem rears its head again. Here are absorption spectra for CaO, Ca(OH)₂, CaCO₃ and TiO₂:

[

Source. Ignore the blue line; this was just the best graph I could find.

[

Source. Ignore the green line.

So, Make Sunsets is using sulfur dioxide, and that’s also what Casey Handmer was keen on in his blog post from June—

Sulfur dioxide reacts with water vapor to produce sulfuric acid, H₂SO₄, which is the main cause of acid rain. This is less scary than it sounds if you’re doing stratospheric aerosol injection—the amount we’d need to cool the earth off won’t lower rainwater pH by very much. Sulfur emissions are much more of a problem in the troposphere, although they have a strong cooling effect even there, as we discovered earlier this year when we shut off sulfur emissions in shipping.

The real problems with using sulfur aerosols are twofold: one, they’re acidic, so in the stratosphere they’ll mess with the ozone layer (calcite, by contrast, helps speed up healing of the ozone hole). Secondly, they’re liquid, which means they glob together and getting particle size right is difficult (and as we saw earlier, getting particle size right is important.)

This would block out light.

It really doesn’t have to block out much. The total amount of radiation reaching the earth’s surface in 1750 was somewhere around 239 watts per square meter, on average ( source); since then we’ve added about four watts via radiative forcing.

It’s also worth noting that data from the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo suggest that its aerosol injection was beneficial to photosynthesis, which does best in slightly diffuse light ( source) 4. (Photosynthesis, remember, only evolved to be good enough—it isn’t an optimized process. See this paper on attempts to improve the operation of the RuBiSco enzyme, which may ring a vague bell from high school bio—it’s a key component in the operation of photosynthesis, but a surprisingly inefficient one. So we shouldn’t really be surprised if photosynthesis operates better in slightly diffuse light than it does on a perfectly clear day.)

How long does this stuff stay in the atmosphere/how much do we need?

The rule of thumb for sulfate aerosols is that one gram of SO₂ will counteract the warming from one ton of CO₂ (i.e., about a million times its own mass) for one year. That’s with sulfate, which, again, tends to coagulate into larger particles.

It’s hard to get good figures for solid particles, but Weisenstein et al. can help us get a ballpark estimate. Here’s figure 1, looking at the sedimentation rates (i.e., rate at which particles fall down) of alumina (Al₂O₃) and sulfate particles.

[

The black line on the graph is average tropical upwelling—in other words, if sedimentation rates downwards are less than the average tropical upwelling velocity, then the particle should stay afloat on average (particularly for the smaller particles in blue—and alumina is denser than calcite). That doesn’t mean they’ll stay up there forever, thankfully—eventually, they’ll migrate to the poles and get snowed out. But this comports with a ballpark figure of two or three years of residence time—we might be able to go back to the temperatures of the early-to-mid 20th century for only 300 kilotons of calcite a year, give or take. (And it’s not that difficult to keep track of how much calcite is up there at a given point—we have spectroscopes far more powerful than are needed to do the job).

I’ve seen criticism that aerosols are a false solution because we’d have to keep putting them up there.

Well, the alternative is that they just stay up there forever and there’s no way to get them out, which is much riskier. Modern civilization is replete with examples of processes that implode if you try to pause them (try booting up a dead power grid without at least one functional power plant, for example). Beware isolated demands for rigor.

Okay, is this going to be bad for the poles?

Less than continued ice melt, which is the really important part. But if you’re worried: about 8% of the Earth’s surface is north of the Arctic Circle or south of the Antarctic—about 41 million km². Let’s suppose we end up using half a megaton of CaCO₃ a year; its density is 2.71 tons per cubic meter, so we’re looking at about 185,000 m³ of the stuff a year. 41 million km² is 41 trillion m², so we’re looking at an evenly-distributed layer of about…4.5 nanometers of calcite. The smallest snowflakes have a diameter of about half a millimeter, more than 100,000 times as wide as the layer is thick. (Note that ice has a lower refractive index than calcite does. And it’s not as if ice sheets don’t have minerals embedded in them!)

Why hydrogen balloons?

~To help Terraform Industries~ ~sell electrolysis units~ because it’s way cheaper than helium at scale. (If you were wondering what happened to the backyard hydrogen production scheme—I think, on balance, that electrolysis is going to win out with cheap enough electricity, and electricity is about to get plenty cheap as solar prices continue to drop). It’s really not that dangerous if you’re careful—not significantly more than methane, for example, which we still use for millions of gas stoves.

One kilo of hydrogen can lift about 1.2 kilos of payload. At current prices, grey hydrogen (produced from natural gas, with attendant carbon emissions) costs about $2 a kilo in the US, though (as you may remember from the backyard hydrogen series) it’s something of a bitch to transport and move around. Terraform Industries 5 is moving in on production of electrolyzers that can produce a kilo of hydrogen for 80 kWh of electricity, at $100 in capex per kilowatt ( relevant blog post); at moderate electricity prices of a dime per kilowatt-hour, that’s eight bucks in opex. This is probably preferable if you don’t have a medium-sized grey hydrogen converter to work with; you’ll have to deal with higher opex, but much lower capex.

Why the tropics?

Because that’s where most solar radiation to the Earth lands. Getting a good sense of exactly how much over a year requires some fairly hairy integrals; we can take a look at this page to try and get a ballpark sense. At noon, the sun reaches its zenith, or highest angle of elevation in the sky, θ = φ - δ, where φ is the latitude and δ is the declination (how far the planet’s axis is tilted against the sun at that time of year). When the sun’s directly overhead, then, light has to get through a certain amount of atmosphere—let’s call it X.

[

Not to scale.

But now let’s look at the situation at 40°N at the summer solstice—about the latitude of New York City.

[

Outside of the tropics, the solstice is where you get the highest zenith angle; in New York it’s about 17 degrees. At the equinox, when δ = 0, it’s just the latitude):

[

To a first approximation, surface irradiance will be inversely proportional to the ratio of the height of the atmosphere to the amount of atmosphere the light actually has to get through—in other words, cos(θ) of the angle between the zenith and vertical. So at noon at the equinox, the total amount of irradiance that hits the Earth is

(where x is an arbitrary unit), and the amount hitting the tropics (between 23.45 degrees south and the same latitude north) is about

or about 39.5%; New York only gets about 77% as much light as the equator will.

But—of course—it gets worse than this, because there’s simply less surface north of the equator; we can set the Earth’s radius to 1 as we’ve implicitly done above and take the chord length, and, uh—

…uh, let’s just write a Python script, which can also look at irradiance on an hour-by-hour basis. It’ll then multiply by the amount of surface area that’s actually at that latitude, estimated by taking the circumference of the circle defined by that line of latitude as a ‘slice’ of the planet. Here’s total irradiance by latitude as a percentage of irradiance at the equator:

[

Middlingly high latitudes like New England or central Europe get considerably less solar radiation than the tropics do, to say nothing of the poles. The case for tropical releases gets clearer when you look at cumulative irradiance by latitude:

[

The 50%-efficiency mark for irradiance at any given point is around 35 degrees, about the latitude of Tokyo or Buenos Aires. But the cumulative fifty-percent threshhold for everywhere at or below a given latitude is at only 20 degrees, about the latitude of Mexico City or Hanoi.

Okay, so, how are you going to release this? 6

This is the biggest unsolved (semi-solved?) technical problem. The thing is that if you just dump a bunch of particles out, they’ll clump together, which we don’t want.

Harvard to the rescue! Harvard’s SCoPEx experiment—more specifically their postdoc Colleen Golja—was, as of April 2021 (the latest update I’ve been able to easily find), working on a mechanism to do exactly this. The main details will be found from about 15:00 on from this interview with her. Essentially, the way to prevent clumping is to have two propellers creating turbulent airflow that scatters the particles to the winds; here’s a picture of SCoPEx’s prototype from figure 1.2 of her dissertation.

[

You get much better results from injecting from the center of each propeller hub (scenario 2, in blue), though it seems plausible to me that further experimentation could find something even more efficient (I am not an expert at esoteric aerodynamics). The propellers don’t go very fast; Golla’s dissertation has them driving the thing forward at about a meter per second, or 3.6 kilometers an hour—a brisk walk.

Right, let’s go back to particle size—

As mentioned before, getting particles of the right size isn’t trivial. However, CaCO₃ is about as harmless as anything else you could imagine putting up there, so we don’t need to get a perfectly narrow distribution centered at 90nm radius; the only real costs associated with particles that are too large or too small are the cost of the hydrogen and the particle spewer, and if manufacturing them at a perfect size distribution is pricier than getting a good-enough distribution and paying for extra hydrogen, that’s what makes sense. This paper by Bahrom et al. was able to get fairly small particles on the order of a micron or so just by mixing calcium chloride (road salt) and sodium carbonate or bicarbonate together in water at room temperature; these are not expensive feedstocks.

Bahrom et al. aren’t terribly interested in particles below the micron scale, but their data can give us some ideas about what we’d be looking to do. The best results are obtained with lower rather than higher salt concentrations, at least when using sodium carbonate (which you can easily produce yourself by putting some baking soda in the oven); sodium bicarbonate (plain baking soda) seems to work a bit better than sodium carbonate, and if reaction γ6 is anything to go by, there seems to be a sweet spot for baking soda if you’re working with about 0.05 moles of bicarbonate ion for each mole of water (that’s about 233 grams of baking soda for each liter of water, if my math’s correct); figure 5 suggests that a reaction time of 10-20 minutes is about perfect for particles of the desired size (you’ll get more clumping and larger particles if you leave it sit for too long). I’m not an expert on these and don’t know whether or not they’ll misbehave if you leave them to sit by themselves in a dry environment; the experimenters used an electron microscope, which I don’t have access to and isn’t really in my price range (if you have access to one in the DC area, feel free to send a note—or, heck, just Do Science On Twitter). There are a number of variables like temperature that this paper didn’t really consider but that might prove important (they did look at temperature with regards to particle shape, but less so for size).

Once you’ve got your propellers, some compressed air, and a good nozzle, I’m guessing you’re probably good to go, though empirical data are again sorely needed. CaCO₃ nanoparticles are light and fluffy (that’s why they stay up there so long, after all), so we’ll want to get some real data on nozzle design. The propellers don’t have to go very fast since they’re producing airflow rather than driving the balloon, and you could plausibly design the nozzle to have a sort of interior wind tunnel so you don’t waste energy from the compressed air. The nanoparticle containers don’t need to be that fancy—glorified cardboard would probably do. The low speed suggests to me that you could make the propellers out of wood or plastic.

I’ve barely seen a single dollar sign so far, let’s talk costs.

If we have 800 grams of total payload for each kilo of hydrogen, we could probably get at least half a kilo of CaCO₃ up to the stratosphere for every kilo of hydrogen used. At 500 kilotons of CaCO₃ needed yearly, that’s around a megaton of hydrogen needed—eight billion dollars a year in hydrogen opex if you’re paying a dime per kilowatt-hour, one to two billion dollars if you’re willing to say ‘screw it’ and use grey hydrogen (the carbon footprint will be considerable, but not that big in the grand scheme of things; get yourself an olivine mine and you can sequester it all for seven or eight figures a year.)

Total cost, including nanoparticles and balloon manufacture: nine figures ($1B < X < $10B) a year. Additional possibilities are likely to present themselves at scale; for example, if you attach a parachute to the payload and tether it, you should be able to recover the machinery 7. Being able to reuse a balloon’s hydrogen even partially represents a significant cost cut, and we’ll look at this in more detail later on.

Can I see some harder budget numbers?

(Thanks to Austin Vernon and Casey Handmer for additional help on the numbers for this section.)

Let’s say we want a battery on board ship to power the electrolyzer. Austin Vernon has a good post) on the economics of battery packs for powering large cargo vessels, but the economics of powering a ship aren’t quite the same as the economics of powering an electrolyzer. Iron-air batteries are heavy and bulky and have low discharge rates (roughly 100 hours to discharge a single battery of any size); that’s a virtue for shipping thousands of containers from Shanghai to Los Angeles, but we only need to go out into international waters (about 50-60 miles round-trip, if that). We could still assume iron-air battery usage for powering the ship (it’s not really all that relevant), but the right battery for electrolysis is a different story.

Let’s assume we’ll be filling something like one of NASA’s [Zero Pressure (ZP) balloons](http://(https//www.nasa.gov/scientific-balloons/types-of-balloons), which can carry a payload of up to 3 tons. We’ll assume 3.6 tons of hydrogen, or 3600 kilos, to carry about 2 tons of calcite and a ton of machinery, leaving 600 kilos for ascent. Each kilo-per-hour will need $8000 in electrolyzer capex and 80 kWh of electricity, so we’ll need 288 MWh of electricity.

We’d need gigawatt-hours’ worth of iron-air batteries to pull this off because they charge and discharge at the speed of molasses, and their energy density by mass is 250 Wh per kilo—a few tens of kilotons. If you can deal with the fire risk, lithium-ion batteries are preferable; they have an energy density by mass about equal to that of iron-air batteries, but can charge and discharge much more quickly, which means energy capacity, not power draw, is the bottleneck. To keep battery lifespan high, we’ll only run them them down from 80% to 20% over three hours, so for each balloon we’ll want 480 MWh in energy storage. Lithium-ion batteries keep getting cheaper; $100/kWh isn’t an unreasonable price to assume in the near future for lithium-iron-phosphate batteries (LFP), with an energy density about equal to that of iron-air batteries, so we’ll want $48M worth of battery per battery pack, weighing 3-4 kilotons (vs. about $100M and 16 kilotons for four gigawatt-hours of iron-air battery). That’s way too much for one shipping container, so it’ll have to be spread across several of them, but you can fit them on a medium-sized container ship.

Nearly fifty million dollars in batteries—Yes, but there are clever ways to cut costs.

We’ll do this with two different kinds of ships: the mothership and the sidekicks. Balloon launching occurs from the mothership, and the sidekicks run battery packs to and from shore. The trick necessary to maintain high throughput is to recycle your hydrogen. LFP batteries take about half an hour to charge from 20% to 80%, but are slower outside of those ranges; my assumption is that they’ll take about as long to discharge at full speed, as well. Austin Vernon has a good post on how this applies to trucking, and I’m drawing heavily on his numbers here.

A weather balloon can reach the stratosphere in two hours. We’ll presume an hour to disperse its payload, and three hours to come back down again at a reasonably safe speed, giving a cycle time of six hours. International waters for our purposes begin 12 miles off the coast; we’ll aim for 15 miles, which should take about 45 minutes to an hour to reach (we’ll call it an hour, but this is probably an overestimate).

We’ll look at a day in the life of a geoengineering ship by starting at 6 AM, when the mothership is 15 miles out to shore. The crew packs the dispenser with a ton and a half of calcite and the necessary compressed air, and switches on the electrolyzers. 480 MWh worth of battery pack spring into action in sequence. When one is drawn down to 20%, it is hoisted by crane onto a sidekick, which pilots it to shore. Every half hour, a sixth of the batteries hit 20% and are hoisted onto a sidekick.

So shortly after 6:30 AM, a batch of sidekicks gets its first batch of batteries (40 MWh total capacity, with 8 MWh of juice left) and pilots them towards shore, arriving just before 7:20. At that point, a crane unloads the old battery pack and replaces it with a fresh one. The sidekick departs shortly before 7:30 and reaches the mothership just after 8:20; by 8:30 AM, the fresh battery pack is back in the saddle.

This makes it easier to run through the logistics of the battery packs. The first balloon in a sequence can actually be inflated much more slowly than we’d otherwise prefer, because you only need enough electricity storage to top the hydrogen off over a six-hour cycle. So: Balloon 1 goes up to the stratosphere (two hours) and disperses its payload (one hour). We then run a pump on board ship that draws 80% of the hydrogen out through the tether and feeds it into Balloon 2, a three-hour process; the remaining 20% (600 kilograms) is lost and has to be replenished anew.

To produce 600 kilograms over three hours, we’ll need 16 MW of electrolyzers (costing $1.6M) and 48 MWh of electricity—call it 50MWh as we’ll also need to run the pump and account for energy loss 8. Assuming 10 MWh per battery pack, then we should be able to get away with surprisingly fewer battery packs by running them to and from shore, in a wolf-sheep-and-cabbage problem.

To wit: we have six 10-MWh battery packs 9 and three sidekicks. A full cycle to or from shore (drop off charged battery pack, pick up depleted pack, sail 15 miles, drop off, pick up) takes an hour, while charging or discharging of battery packs takes thirty minutes. At 6 AM, there are two fully charged packs on board the mothership, one of which has just been switched on. Sidekick A is taking a depleted pack to shore; sidekick B has just plugged in a depleted pack and picked up a fresh one; and sidekick C is transporting a fresh pack to the mothership.

[

Thirty minutes later, the sidekicks rotate. One of the packs on board ship has been depleted and is picked up by sidekick C, which has just dropped its pack off. Sidekick A is in sidekick B’s old place (switching packs at shore), and sidekick B is in sidekick C’s old place (transporting to the mothership).

[

So every thirty minutes one of the positions (loading at mothership, transporting a depleted pack to shore, switching packs at shore, transporting a full pack to the mothership) is empty, but the mothership always has two fully charged packs to work with.

[

(We can probably go out even further into international waters if we have sidekicks meeting at the halfway point to swap battery packs.)

Total cost for the lithium-ion battery packs is about $6M and dropping; less than that if you can save more than 20% of your hydrogen from run to run. Doing so would also save on power draw; in this scenario we’ll need a 20MW power source (about $16M in capex at current solar-panel prices, but dropping rapidly), but the more hydrogen you can recycle, the less power and fewer batteries you’ll need 10.

How does this affect costs?

Enormously.

Again: under this setup, we only need about $6M of battery packs, $1.6M in electrolyzers, and a 20MW power source—imminently $16M in capex and dropping—plus a few boats. If we weren’t going to cycle hydrogen, then we’d be looking at five times as much in power supply and electrolyzers, and a painful trade-off to make between much higher cycle time and additional battery packs. 11

With this setup, it’s possible to launch four balloons a day with a six-hour cycle time—8 tons of calcite in total, around 2.56 kilotons a year if you’re running operations 320 days a year and launching 1,280 balloons. We’ll amortize the solar plant and electrolyzers over 30 years and the battery packs over five, giving approximate opex costs of about $2.2M a year before the ships, if you didn’t borrow money to buy the capital. Total cost for 500 kilotons of calcite a year is about $440M and quite plausibly less.

A ship is a hole in the water you throw money into.

At any given point, there’ll be up to three battery packs on the ship, and those are the biggest cost centers; see footnote 10. At 10 MWh, each of the six battery packs will weigh about 40 tons, or a bit under two shipping containers’ worth. We don’t necessarily need exactly six battery packs; we just need to split them into six groups.

Ships’ cargo capacity is measured in TEUs, where each TEU can carry about 24 tons of cargo. A geared (i.e., with its own cargo crane) 500-TEU container ship in good condition can be had for about $4-6M used and can carry about 12 kilotons of cargo, far more than we actually need; the sidekicks will cost less. We could probably get the necessary ships for about $10M total; we’ll presume $1M for fuel, maintenance and crew (“shore” is probably in a stable but developing country, if only because there aren’t many large, developed countries at the equator), which may be an overestimate. Amortize the ships’ capex cost over 20 years before interest, and we’re at a total yearly cost of $3.7M.

Again: f that $3.7M, you get 2.56 kilotons of calcite launches a year, fixing the heating footprint from at least 2.56 gigatons CO₂ equivalent and probably considerably more because calcite has a higher residence time than sulfur dioxide. Chump change—

Sorry, I thought this was do-it-yourself.

I mean, nothing’s stopping you from a scaled-down version of this with fewer electrolyzers or a pressurized tank of hydrogen, if you’ve got a sailboat 12—though see the footnote.

Okay, and the international waters bit—

The FAA hath no jurisdiction in this realm.

If you launch from your backyard in the States, your max payload is six pounds (2.4 kilos), or two separate six-pound payloads, before the FAA starts putting all sorts of rules on you (assuming they notice, of course).

Of course, it could still be worthwhile, and fairly cheap if you have an electrolyzer at home. You could plausibly launch about 1.5 kilos of calcite this way with a miniature propeller-gadget hooked up to a Raspberry Pi hooked up to an altimeter, which would be enough to offset the heat from about 1.5 kilotons of CO₂-equivalent.

So, get a million people making these, and—

And then you’re offsetting about a gigaton per year or more if they each launch one miniature version a year, depending on latitude (the FAA doesn’t have much jurisdiction around the equator, though). It’s probably not that hard to manufacture, especially if the propellers are powered at least in part by the compressed air. You’d need to buy a new one every time, though, since you’re not really supposed to tether these things (small ones won’t be worth pulling down in any case).

But scale matters, even if the scale needed to cancel out the heat footprint of a trillion tons of carbon is smaller than the scale needed to sequester it. It’s possible for a handful of individuals to make a serious dent in industrial heating! But it’ll go most smoothly if some of those individuals are contrarian shipping magnates.

Nephew Jonathan, September 16th, 2023