J. Carlos Roldán Passwordless a Different Kind of Hell

J. Carlos Roldán / Passwordless: a different kind of hell? #

Excerpt #

It’s no secret that authenticating into services is an unresolved topic. With time, we have managed to make them more secure, but that was at the expense of user experience. The new generation of mail codes and authenticator apps has moved us from the ease of one-click browser autocomplete to complex ordeals involving multiple steps and sometimes multiple devices.

It’s no secret that authenticating into services is an unresolved topic. With time, we have managed to make them more secure, but that was at the expense of user experience. The new generation of mail codes and authenticator apps has moved us from the ease of one-click browser autocomplete to complex ordeals involving multiple steps and sometimes multiple devices.

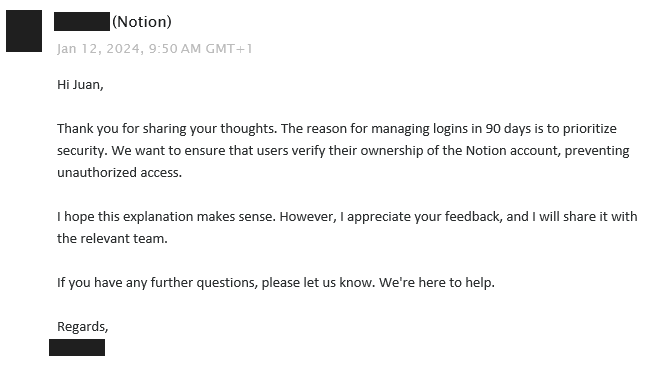

Last month, I was logging into Notion after it automatically logged me out, and I couldn’t help but think “It feels like I’m logging in here every second week; maybe I’m doing something wrong.” After a long examination of the settings, I decided to open a ticket asking if the session length was indeed that short. The response from Notion’s team was prompt and specific, a great example of customer service. However, the content of the answer was less pleasing.

Notion is not alone in this; many other services enforce similarly short sessions and uncomfortable methods. This has me pondering the evolution of our authentication methods, from their ancient beginnings to modern complexities. Let’s take a look at the history of authentication methods and rate them on two scales: user experience and security.

The first recorded password in western history is the book of Judges. Within the text, Gileadite soldiers used the word “shibboleth” to detect their enemies, the Ephraimites. The Ephraimites spoke in a different dialect so that they would say “sibboleth” instead. Experience ★★★★★: you just had to say a word. Security ☆☆☆☆☆: there’s a single word to authenticate multiple users and it can be cracked by learning how to spell it.

Ancient Romans also relied on passwords in a similar manner called them “watchwords”. Every night, roman military guards would pass around a wooden tablet with the watchword inscribed and every military man would pass the tablet around until every encampment marked their initials. During night patrols, soldiers would whisper the watchword to identify allies. Experience ★★★☆☆: you just had to say a word but you have to memorize it every day. Security ★☆☆☆☆: it changes every day, but it’s still a single word, and without a “forgot password” button, a wrong answer would mean a spear in the gut.

Fast forward to the ’20s, alcohol became illegal in the US, and speakeasies (illegal drinking establishments) were born. To enter the speakeasy, people had to quietly whisper a code word to keep law enforcement from finding out. Code words were ridiculous, to say the least: coffin varnish, monkey rum, panther sweat, and tarantula juice, to name a few. Experience ★★★★☆: you just had to say a word, and they were made to be memorable. Security ★☆☆☆☆: it’s a single word, and it’s not even a secret, but at least you don’t get stabbed for getting it wrong.

The first recorded usage of a password in the digital age is attributed to Dr. Fernando Corbató. In the 60’s, monolithic machines could only work on one problem at a time, which meant that the queue of jobs waiting to be processed was huge and a lot of processing time was lost. He developed an operating system called the Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) that broke large processing tasks into smaller components and gave small slices of time to each task. Since multiple users were sharing one computer, files had to be assigned to individual researchers and available only to them, so he gave every user a unique name and password to access their files stored in the database. However, these passwords were stored in a plaintext file in the computer and there were a few cases of accidental and intentional password leaks. Experience ★★★☆☆: you have to remember a user and password. Security ★★☆☆☆: it’s one per user, but they’re stored in plaintext.

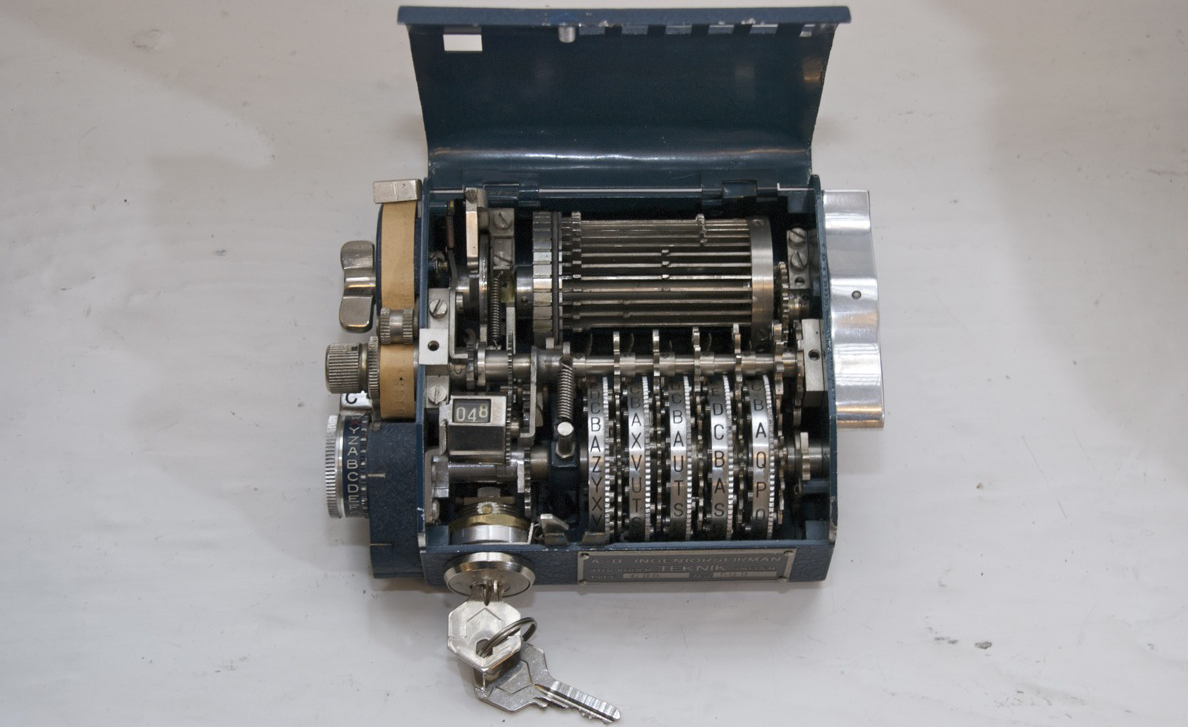

To prevent the problem of plaintext passwords, Robert Morris and Ken Thompson developed a simulation of a World War 2 crypto machine that scrambled the password before storing it into the system. This way, the system could ask for the password, scramble it, and compare it to the scrambled password stored in the system, a process called one-way hashing. This simulation was included in 6th Edition Unix in 1974, and got several improvements up to our days, but the basic idea remains the same. Experience ★★★☆☆: you have to remember a user and password. Security ★★★☆☆: it’s no longer plaintext, but stealing it would still give you access to the system.

Over time, many different problems arised from the fact that people use the same password for multiple services, so the industry started to push for unique passwords for each service. This was a problem for users, since they had to remember a lot of passwords, and password managers were borned. The first password manager was developed by Bruce Schneier in 1997, and currently every major browser comes with a built-in one, often with an option to generate strong passwords and store them for you. Experience ★★★★☆: you have to remember a master password, but the browser remembers the rest. Security ★★★★☆: it’s no longer plaintext, but the master password is the weakest link in the chain.

Phishing attacks and data breaches have made passwords a liability, so the industry has been pushing for multiple-factor authentication (MFA) for a while now. 2FA is a method of authentication that requires two different factors to verify your identity. The first factor is usually something you know, like a password, and the second factor is something you have, like a phone. This way, even if someone steals your password, they still need your phone to log in. There is a myriad of ways to implement 2FA, but the most common ones are SMS codes, authenticator apps, and mail codes. It is often used in conjunction with very short session lengths. Experience ☆☆☆☆☆: you have to remember something, have a phone or mail app, and it requires multiple steps. Security ★★★★☆: it’s no longer a single factor, but it’s still vulnerable to phishing attacks.

I, like most people, hate passwords and all means of authentication bureaucracy. And it looks like we’re now at the lowest point in history in terms of UX. There is still hope with the rise of Single Sign-On (SSO) and biometrics. And certainly passkeys, which are getting a lot of traction lately, are a step in the right direction. But only time will tell if their adoption will be widespread enough to make a difference or if we’ll be stuck in this dark age of authentication experience for a while.

Related posts: