How to Apply Creational Design Patterns to Craft Flexible Software Level Up Coding

How to Apply Creational Design Patterns to Craft Flexible Software | Level Up Coding #

Excerpt #

A six step refactoring process with a case study to explore design patterns: Factory, Abstract Factory, Builder – and tips to well architect your software

A 6-Step Refactoring Process with a Case Study to Explore Design Patterns: Factory, Abstract Factory, Builder. #

[

]( https://medium.com/@jogi47?source=post_page-----2caa09e540ed--------------------------------)[

]( https://levelup.gitconnected.com/?source=post_page-----2caa09e540ed--------------------------------)

Creating clean designs ultimately boils down to an intuitive approach #

To make your code clean, you begin by relocating its noise elsewhere. Then, you patiently wait until you detect any signal within that noise. As soon as you identify it, you filter out that signal and relocate the remaining noise elsewhere. You continue this process, progressively moving the noise further away from the callee to the caller. Ultimately, it’s the client or the client’s client who deals with that noise until they discover patterns and clean it up by relocating its noise elsewhere.

If this sounds a bit abstract, let’s dive deep to learn it step by step.

What you will learn from this blog? #

- How creational design patterns can effectively separate the hard-wiring of your code from your core business logic.

- How various creational design patterns are interconnected and which pattern is suitable for different stages of your software’s evolution.

- How to leverage abstraction as a tool to introduce discipline into your procedural code.

- Recognizing the right time to refactor your code and understanding the role of the business domain in making key decisions.

Image created with maze.guru

Below is the quote from Eric Evans’ “Domain-Driven Design” book — It is a profound analogy that beautifully illustrates the importance of separating the creation of objects from their actual use. It’s bit long quote but you have to give your full attention as it holds the essence of creational designs patterns.

A car engine is an intricate piece of machinery, with dozens of parts collaborating to perform the engine’s responsibility: to turn a shaft. One could imagine trying to design an engine block that could grab on to a set of pistons and insert them into its cylinders, spark plugs that would find their sockets and screw themselves in. But it seems unlikely that such a complicated machine would be as reliable or as efficient as our typical engines are. Instead, we accept that something else will assemble the pieces. Perhaps it will be a human mechanic or perhaps it will be an industrial robot. Both the robot and the human are actually more complex than the engine they assemble. The job of assembling parts is completely unrelated to the job of spinning a shaft. The assemblers function only during the creation of the car — you don’t need a robot or a mechanic with you when you’re driving. Because cars are never assembled and driven at the same time, there is no value in combining both of these functions into the same mechanism. Likewise, assembling a complex compound object is a job that is best separated from whatever job that object will have to do when it finished.

— Eric Evans

Once you understand that car driving is not same as car manufacuring, hence the object your program consume doesn’t care who creates it, you’ll be ready to grasp the concept of factory methods. Without this fundamental understanding, using creational patterns might seem confusing or overwhelming.

Introduction #

One of the fundamental and perhaps the most crucial aspects of any software is its maintainability. It is a key attribute of software quality and is essential for the long-term viability and cost-effectiveness of software applications. To ensure that your software lasts for decades and remains flexible and extensible, low-level design plays a pivotal role.

Design patterns are the backbone of low-level software design. They were introduced by the Gang of Four (GoF) in the 1990s and have become some of the most popular design patterns in the software development world. In this blog, we will delve into creational design patterns, accompanied by interesting examples to help you better comprehend them.

According to the Gang of Four, there are five creational design patterns. In this blog, we will focus on learning three of these design patterns, as the remaining two are relatively easier to grasp. So, let’s dive in and gain a deeper understanding of these essential concepts.

Our Case Study #

Let’s consider the HR Payroll system of an IT organization as a sample software to explore these design patterns. They use this system for managing the payroll of its employees. This system encompasses various modules, as you would find in any other payroll system. However, for the purpose of this blog, we will concentrate on the module responsible for calculating employee incentives.

We’ll start our low-level design with the simplest architecture and gradually progress to more complex structures.

Throughout this journey, we will document our decision-making process and ultimately arrive at an advanced architecture that adheres to clean architecture principles.

Level 0 #

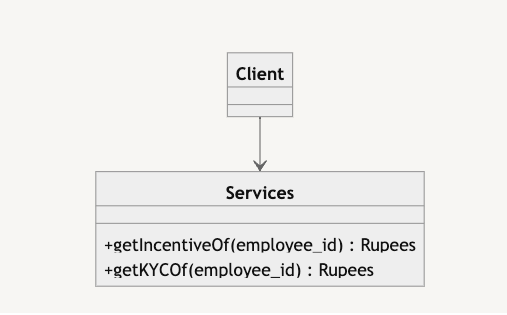

Our Incentive Module begins (and ends) with just one file, which we’ll refer to as `service.xy` (where `xy` represents the file extension of your favorite programming language). It’s important to note that this service file handles more than just calculating incentives; clients will utilize this service for various other purposes.

In above figure, you can observe a method named `getIncentiveOf`, which takes one argument called `employee_id`. Based on this employee_id, the method determines the respective incentive for the employee as of the current date. Clients will invoke this method to retrieve the incentive amount for that employee in the current year.

While this may seem straightforward at a high level, let’s take a closer look at what’s happening within this method. Calculating incentives is far from easy; it involves intricate business logic and numerous parameters. It’s crucial to segregate the concerns of each step in this calculation to keep them Independent and Testable. The last thing anyone wants is to compromise the integrity of the payroll system of any organisation. So, let’s get serious about low-level design and take it to the next level.

Level 1 #

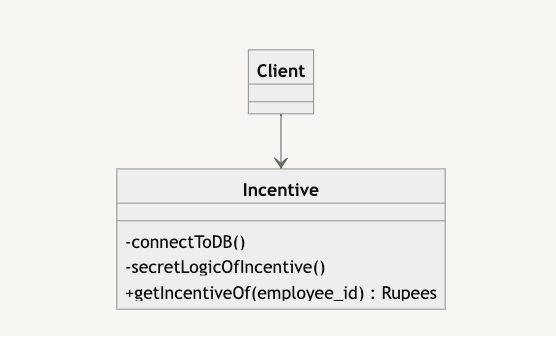

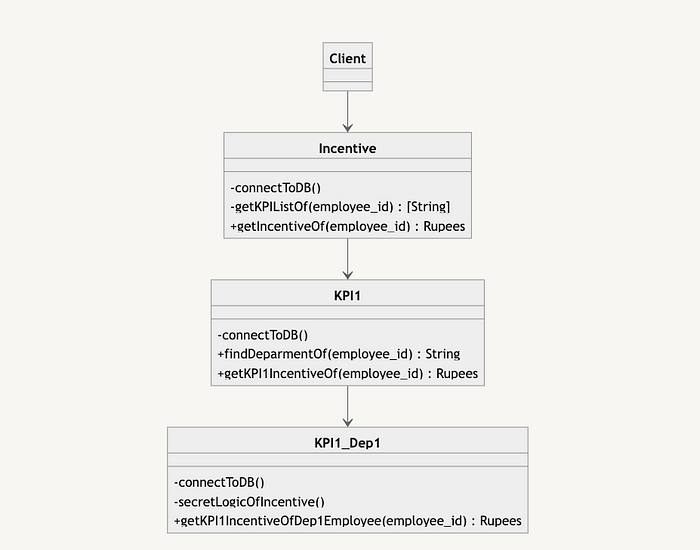

The most obvious step is to separate our Incentive services into different file. Clients will create an object of the Incentive class and make calls to find the incentive. This approach allows us to encapsulate the incentive calculation logic into separate methods, making the code more modular and easier to maintain. It would look something like below.

The Bigger Picture #

To provide some context, let’s consider this module as a single-tier web application where we have an `IncentiveController` that requests the incentive of a particular employee to pass it on to another system. This client, acting like our “postman”, is responsible for executing the work. In essence, we don’t concern ourselves with what they will do with this information; our sole focus is to determine the incentive of that employee. To find this incentive, the controller needs to connect to a database, retrieve the required information, and process it.

As mentioned earlier, calculating incentives is a complex task involving various parameters. Some of these include employee attendance, which directly impacts the incentive. Additionally, there may be project performance data, Number of lines of code committed by a developer and contributions to open-source libraries. For the HR department, factors like employee retention come into play. It’s important to note that all this information may reside in different databases, and some data might even need to be fetched from third-party services.

func getIncentiveOf(employee_id) -> Rupees { }

Additionally, there can be customized settings for individual employees. However, as this blog focuses on design patterns rather than payroll system specifics, let’s abstract these details as KPIs (Key Performance Indicator). Whenever we mention KPIs, please consider one of the conditions mentioned above. This approach allows us to place a stronger emphasis on the concepts of design patterns.

Level 2 #

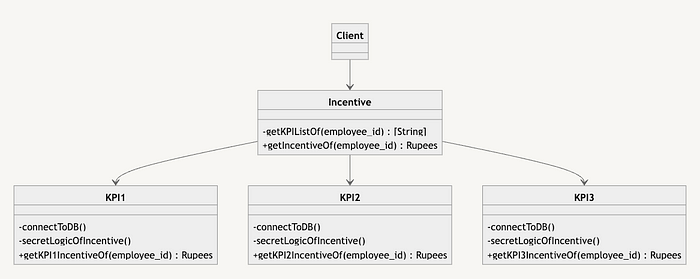

Now it’s time to divide the `Incentive` class into different classes. One obvious way to do this is to group them by their KPIs. Each KPI functions differently and has its own unique settings. Creating separate KPI classes for each KPI is a sound approach. This not only makes each KPI independently testable but also ensures that if the software owner requests changes to a specific KPI calculation, we can make those changes without affecting other KPIs.

The `Incentive` class will create objects of each KPI class, request incentives for each KPI, and then sum up all the incentives to send to the client. The final structure would look something like this.

It’s important to note that the `Incentive` class needs to first identify all the KPIs applicable to a particular employee. Based on this list of KPIs, the `Incentive` class will select the appropriate KPI class to request the incentive from.

Level 3 #

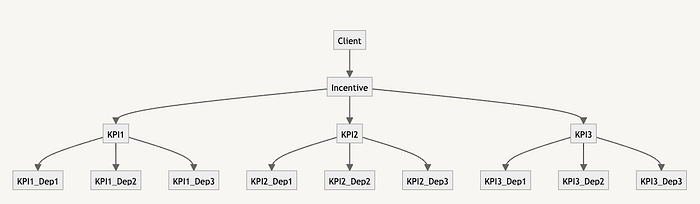

As you can see, we have now divided the logic into different classes and clearly defined each one’s responsibility. However, that’s not the end of our design journey. If we look inside each KPI, we encounter another condition: the employee’s department. KPI standards can vary depending on the department, and these variations affect the incentive system differently. It’s time to further separate the logic based on departments. So, we will create classes for each KPI according to the departments within the organization. The structure might look something like this:

To summarize how things work #

- When a client calls `Incentive` with an `employee_id`, `Incentive` fetches the list of applicable KPIs for that employee.

- It then makes a call to each KPI class. While calling a specific KPI class, it checks the employee’s department and, based on that, creates an object of the appropriate `KPI+Dep` class and calls its method to calculate the incentive for that KPI.

- The calculated value is then passed back to the `Incentive` class. `Incentive` class will sum up incentive amount from each KPI and give that to Client.

Level 4 #

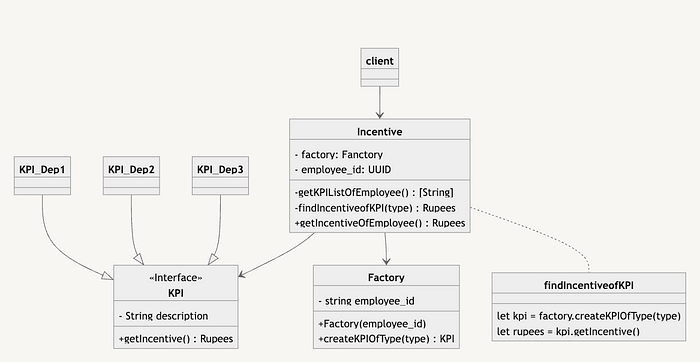

At this stage, we can identify some issues with our system. We’ve ended up with many different classes that essentially perform the same task at a high level but with different implementations. It’s time to introduce abstraction to bring some discipline into our design.

Furthermore, there are numerous dependencies between classes, and the code isn’t as modularized as it should be. We’ve created a chain of object creation where each class depends on the previous one. To ensure our code is more modular and extensible for future additions of new KPIs, we should introduce the Creational Design Patterns.

The creational design pattern simplifies object creation by centralizing it in a Factory method. This method takes responsibility for creating the appropriate objects, relieving intermediate classes from making those decisions. In our case, the KPI classes were responsible for checking the employee’s department and creating the corresponding object. This approach is not sustainable for the long-term durability of the software.

Another advantage of introducing the Creational pattern is that it reduces dependencies. Previously, all objects were aware of each other, creating a chain of object creation. With the Factory method, it handles all the wiring, eliminating the need for intermediate classes to perform this task.

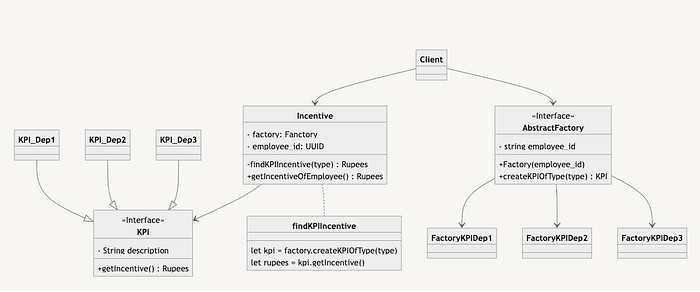

Our desired end goal is to have the appropriate `KPI+Dep` class provided to the `Incentive` class. #

The `Incentive` class shouldn’t concern itself with the concrete classes it’s working with. To achieve that, we’re moving the logic for creating all objects back to the Factory. It will check the employee’s department and create the respective object, passing it to `Incentive`. Now, the `Incentive` class doesn’t need to know about the concrete objects it’s working with.

In the new design, `Incentive` class will simply call the `findKPIIncentive(type)` method to obtain the appropriate KPI object. These KPI objects will have a `getIncentive` method to provide the incentive for that specific KPI.

Instead of having the client use a single `Incentive` object to fetch employee incentives, it would be more organized for the client to create different objects for different requests. This approach ensures that we don’t encounter shared properties that could potentially corrupt our data. This aligns with the programming notion of Pure Functions, where one function, for a given input, produces the same output.

It’s worth noting that the logic regarding how many KPIs exist and what each individual KPI’s incentive calculation entails is still within the `getIncentiveOfEmployee` method. For now, we’ll leave it there as it’s not part of the isolation process we’re currently focusing on.

Realization on Creational Design Patterns #

This scenario exemplifies the typical use case of a Creational Pattern. It extracts all the creation logic from other business logic, providing us with the respective object we need. In the example above, the `Incentive` class, given an `employee_id` and the type of KPI required, relies on the Factory to determine the correct object to pass back to the `Incentive` class.

The `Incentive` class treats all KPIs uniformly, without going into the concrete classes. This design choice makes the system highly extensible.

If you introduce a new KPI with either complex or straightforward logic, you can follow these steps: #

- Create a `KPI+Dep` class for the new KPI and ensure it conforms to the KPI interface.

- Add support for the new KPI type to the Factory method. This type will be passed by the `Incentive` class.

- In the `Incentive` class, maintain a list of KPI names/types, and extend it to accommodate the new KPI type.

This approach ensures that your system can easily adapt to changes and additions of new KPIs, making it more robust and maintainable in the long run.

Level 5 #

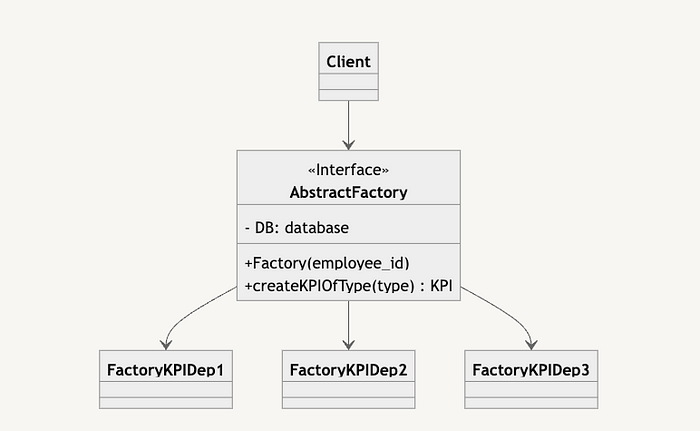

Everything appears to be going well so far. We’ve realized that factories are like mysterious black boxes where you provide minimal information and, in return, receive the objects you need. However, these factories tend to contain a lot of procedural code. As we continue to add more KPIs, this code complexity can increase significantly. It’s a good idea to introduce some discipline within these classes by incorporating abstraction, which we’ll refer to as the Abstract Factory Pattern.

What do I mean by “procedural code,” let me elaborate #

Our factory isn’t merely checking the department and creating the respective department concrete class; it’s doing much more than that. Each department KPI requires some properties that still need to be initialized. While it’s possible to initialize these properties inside the KPI class, why should we do that? Instead, we can demand a fully configured class from the factory, so all the KPI class needs to do is run the operation, retrieve data, and perform business logic. Thus, the factory has a lot more going on, depending on the department KPI class it needs to create. To better understand this, check the code snippet inside the factory method:

func createKPIofType(type: String) -> KPI { }

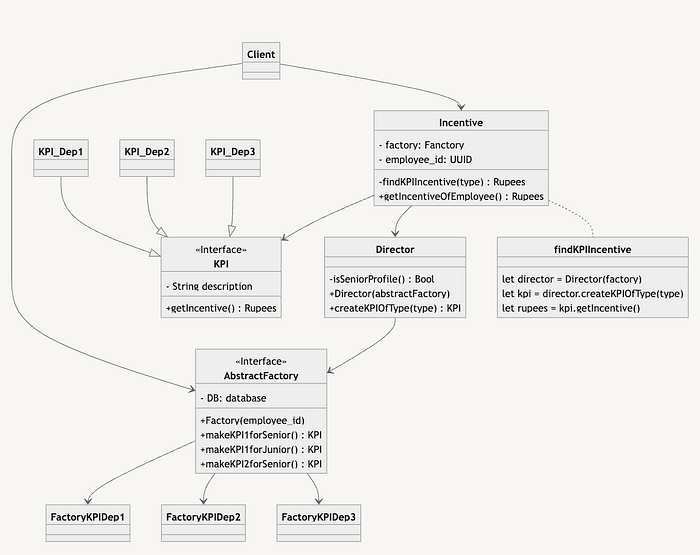

As you can see in the below figure, rather than keeping the creation logic inside the factory class, we’ve introduced abstraction in the form of an interface called `AbstractFactory`. This interface is implemented by each department-specific factory.

A more effective approach is to have the `Factory` as an abstract class and the department factories as concrete classes.

How do we determine which factory to create in the `Incentive` class? #

It’s better to let the client decide this. The client will pass the respective Factory object to `Incentive`, and the `Incentive` class will use this factory to create KPI objects. The end result looks something like this:

In essence, we’ve divided the creation logic for all KPIs department-wise. This means that each of our concrete factory classes only has to deal with one department, providing us with a cleaner, more focused playground for working with each department at a time.

This level of abstraction and separation of concerns greatly enhances the maintainability and scalability of our system, making it easier to add new KPIs and departments in the future.

Level 6 #

Moving forward, let’s dive into the Builder Pattern. Imagine we encounter a bit more complexity in our incentive calculation. Specifically, different algorithms are applied based on the employee’s experience. For example, if a department employee has more than 5 years of experience, we need to consider different properties of KPI classes. Currently, this logic resides within the Factory KPI classes, which introduces some procedural code. It would be beneficial to introduce some structure to handle this.

In this setup, the `Incentive` class will hold a reference to the `Director` class. `Incentive` will initialize the `Director` with an `AbstractFactory` object provided by the Client. Depending on the experience of the employee, the `Director` will provide the appropriate KPI objects. The end result will resemble this:

All of the procedural logic is now contained within the `Director` class. The `createKPIofType` method will look something like this:

func createKPIofType(type: String) -> KPI { if (type "kpi1") { if (isSerniorProfile()) { return makeKPI1forSenior() } else { return makeKPI1forJunior() } } else if (type "kpi2") { } else if (type == "kpi3") { } }

Now, the Factory classes are primarily responsible for constructing individual KPI objects for senior or junior employees. If we introduce new KPIs or need to modify the existing logic for current KPIs, the Factory class owners will know where to make changes without altering the wiring or structural aspects.

By incorporating the Builder pattern in our design, we’ve further enhanced the maintainability and flexibility of our system, particularly in handling different algorithms based on employee experience.

Summary #

We started on a journey from a simple and minimal architecture to a complex one. Along the way, we made crucial design decisions aligned with our business goals. These decisions can’t be made in isolation, it should always align with nature of software or buisness needs.

For the same HR payroll system, different decisions would have been made if our business needs were different (In this case, our logic for calculating incentives differed). Keep in mind that needs may change over time, but the right decisions will always provide room for changes with ease.

Let’s examine these decisions #

We grouped business classes by KPI, then further grouped them by employee department, and finally, these KPI+Department combinations were categorized by years of experience.

This is a business-driven choice, and while it remains adaptable, such decisions are something we can abstract and discuss with domain owners who have a clear understanding of potential future modifications to the incentive calculation formula.

What if you realize that two KPIs are very similar, with only minor logic differences? #

Would you consider combining them into one class? The answer is NO. This principle aligns with the Single Responsibility Principle. While you may be tempted to group them by logic, remember that business rules take precedence. In the future, changes may widen the gap between these two KPIs or confuse new developers as architecture rules are not kept the same across the software. So, choose your designs diligently.

As we impose discipline in our code, it aids in scaling our software development. By creating more isolated components, we can have separate development teams work on specific logic without concern for the bigger picture. Consider any significant open-source software project, and you’ll find hundreds of developers in their isolated rooms.

At each level, we were picking some kind of hard-wiring logic and throwing it out of our closed system. Of course somebody has to be owner of that and there is no right place then factories. To make any system independant — provide them with data which they work upon to get back the output. How they acquire that data? They don’t care; it’s their client’s responsibility to provide the right data.

Abstractions are the means to transform procedural code into disciplined code. Objects dealing with these abstracted classes don’t need to be aware of implementation details. When you realize this, you’ll see that all design patterns essentially serve the same purpose: providing different ways to abstract and structure code.

Let’s end this article with a quote from Christopher Alexander, who inspire Eric Gamma to make such beautiful book on Design Patterns.

About me: I’m Jigar, a software designer at Yudiz Solutions. I’m an avid reader and have a keen interest in exploring the IT industry. During my free time, I explore different topics of Theoretical Physics.